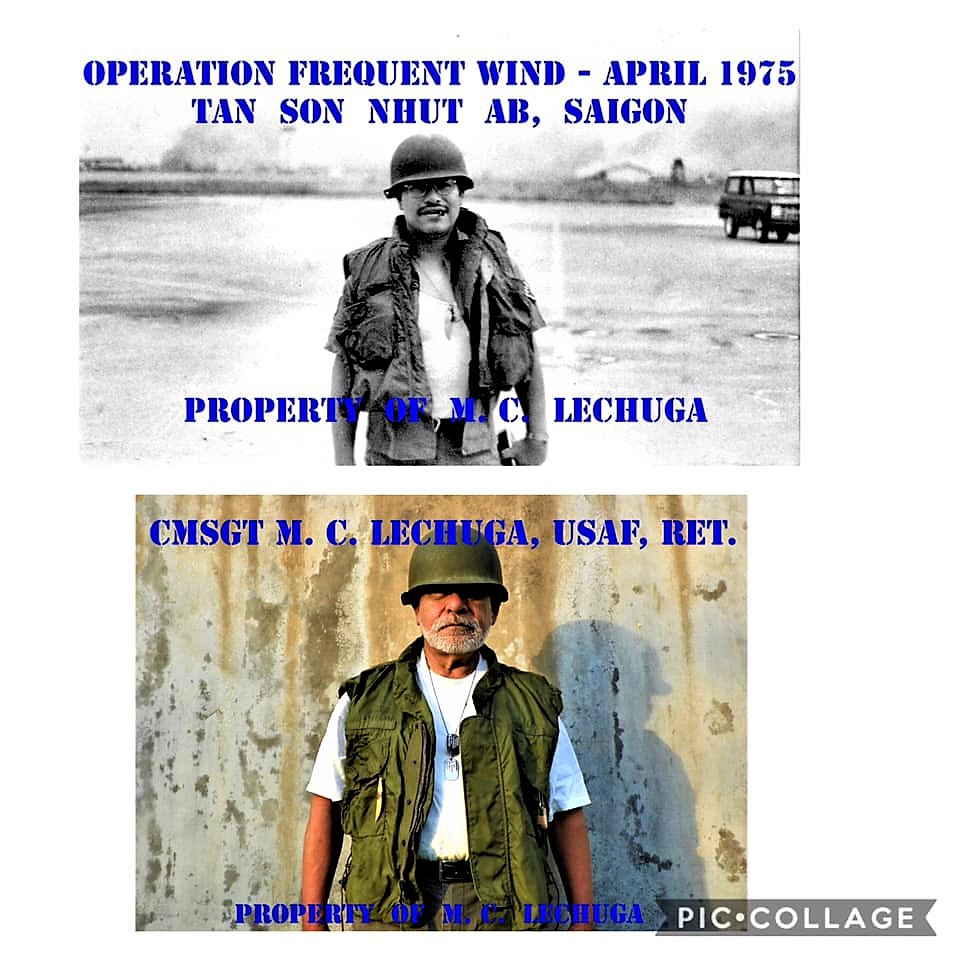

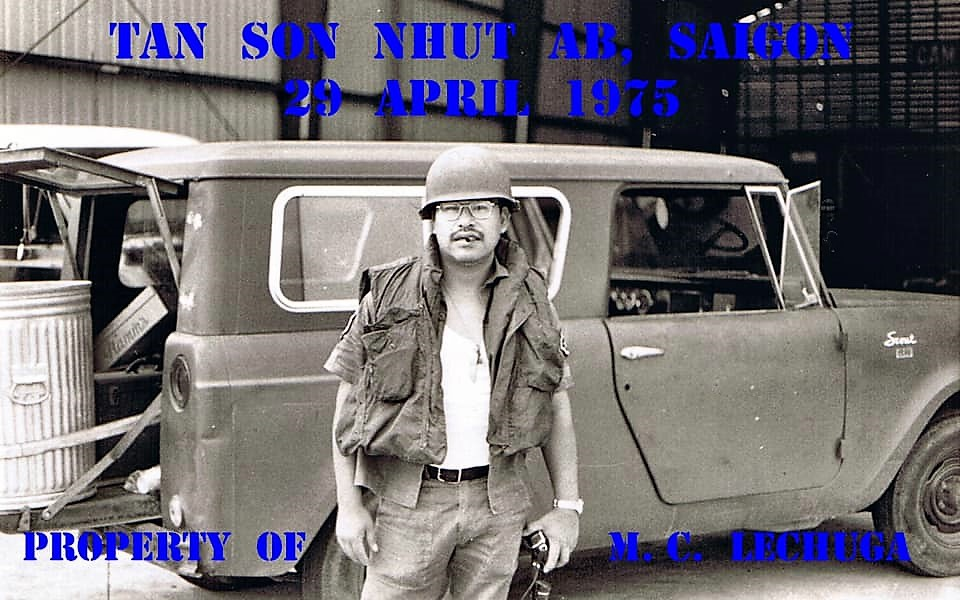

USAF SSgt Miguel (Mike) Lechuga

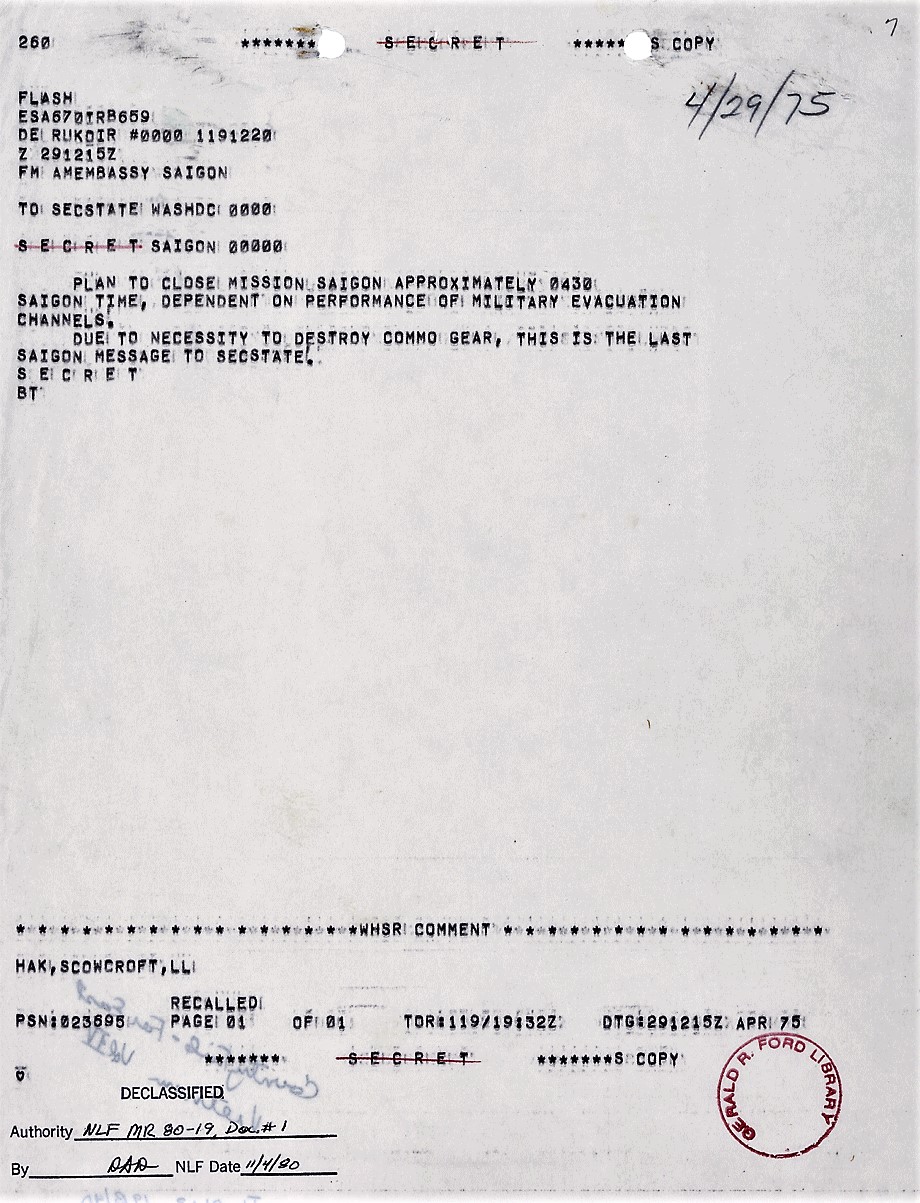

Eyewitness to the fall of Saigon, South Vietnam – April 1975

______________________________________________________

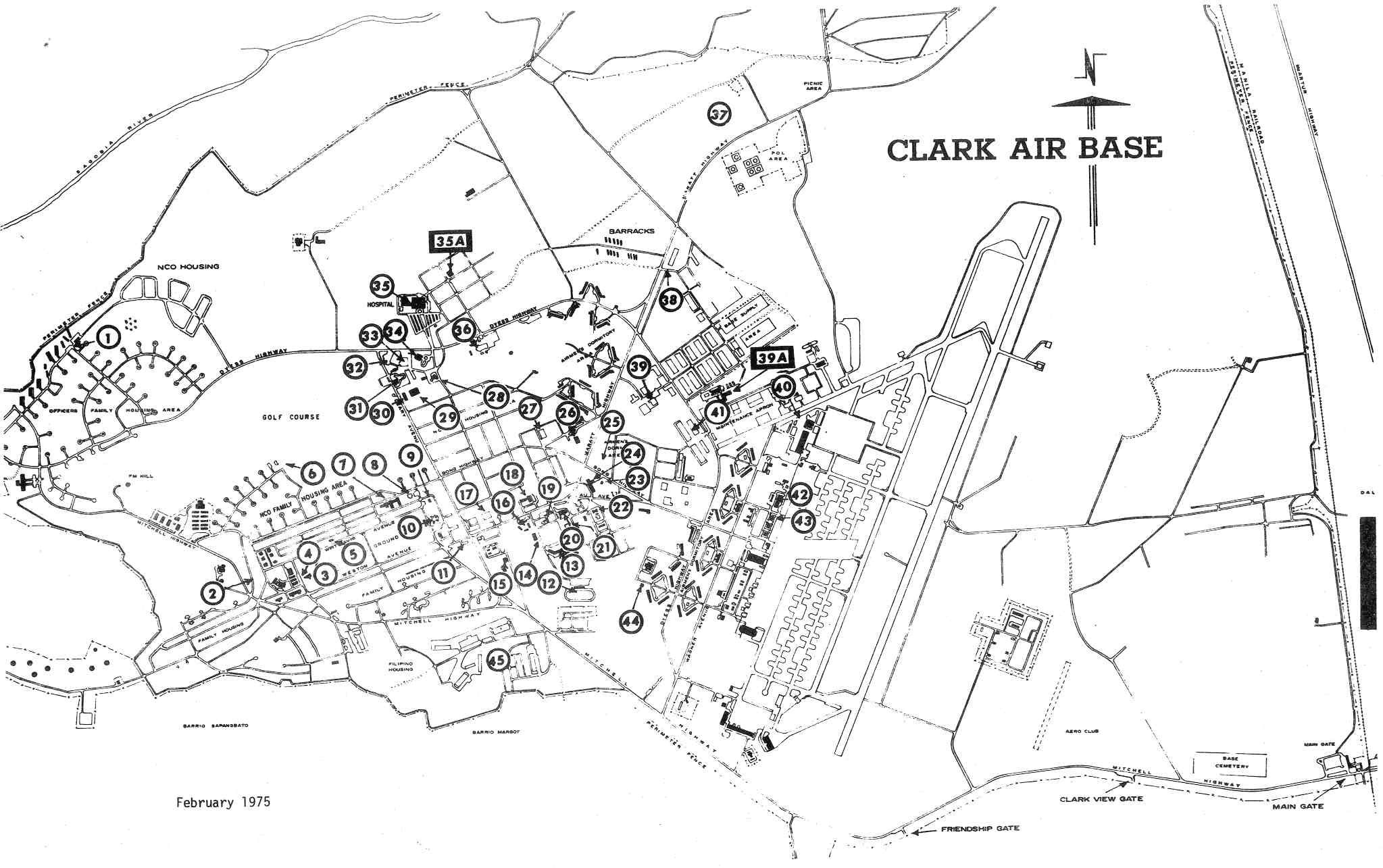

This the story of US Air Force SSgt Miguel (Mike) Lechuga and his experiences during the fall of Saigon in April 1975. We begin his journey at Clark AB in the Philippines. SSgt Lechuga was one of over 14,000 American service men and family members stationed at Clark AB during 1975.

About 40 miles north of Manila, Clark AB was originally established as Clark Field in 1919, a part of the US Army’s Fort Stotsenburg which had been established in 1903. It grew to become the largest US air base in the world and was a major logistic hub during the Vietnam war.

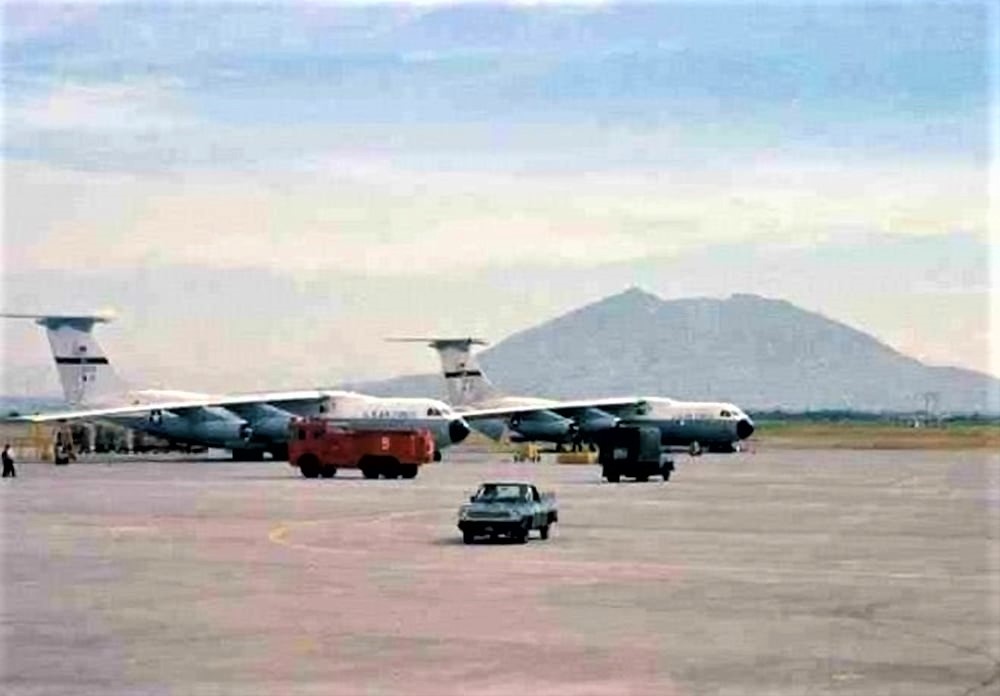

It’s single long runway supported large civilian airliners and the USAF cargo fleet of C5s, C141, and C130s. In 1975, Clark AB was still a major support base for the 27,000 US forces stationed in Thailand at five main bases. The ground support of the C5, C141, and commercial contract aircraft at Clark AB was handled by the 604th Military Airlift Support Squadron (MASS).

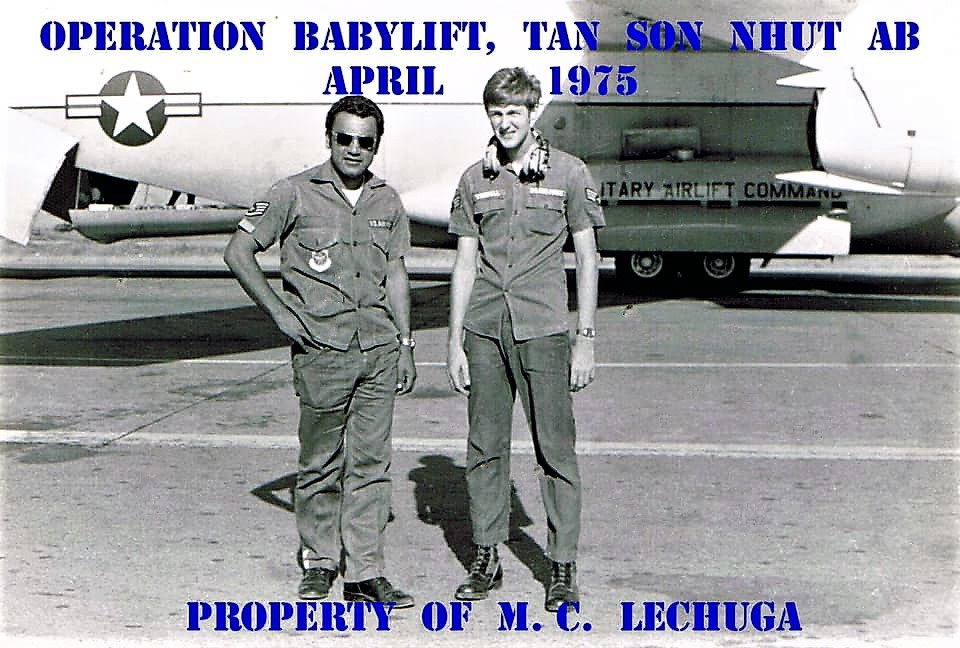

SSgt Lechuga was an Aircraft Avionics Specialist with the 604th Military Airlift Support Squadron at Clark AB, Philippines, where he performed maintenance on the Military Airlift Command’s C-141s and C-5s. Clark AB was in a peacetime environment at that time, which meant regular but long hours on the flight line.

_____________________________________________

The United States had officially pulled her combat troops out of South Vietnam in 1973. Under the Paris Peace Accords, the United States could only have 50 active duty military people, other than the USMC embassy guards, in Vietnam at one time. A total of 209 military personnel remained in South Vietnam (50 officers from all services at the Defense Attache Office and 159 Marine guards assigned to the Saigon Embassy and the four Consul General offices at Da Nang, Nha Trang, Bien Hoa, and Can Tho). This was a far cry from the 549,500 US servicemen in Vietnam in 1968.

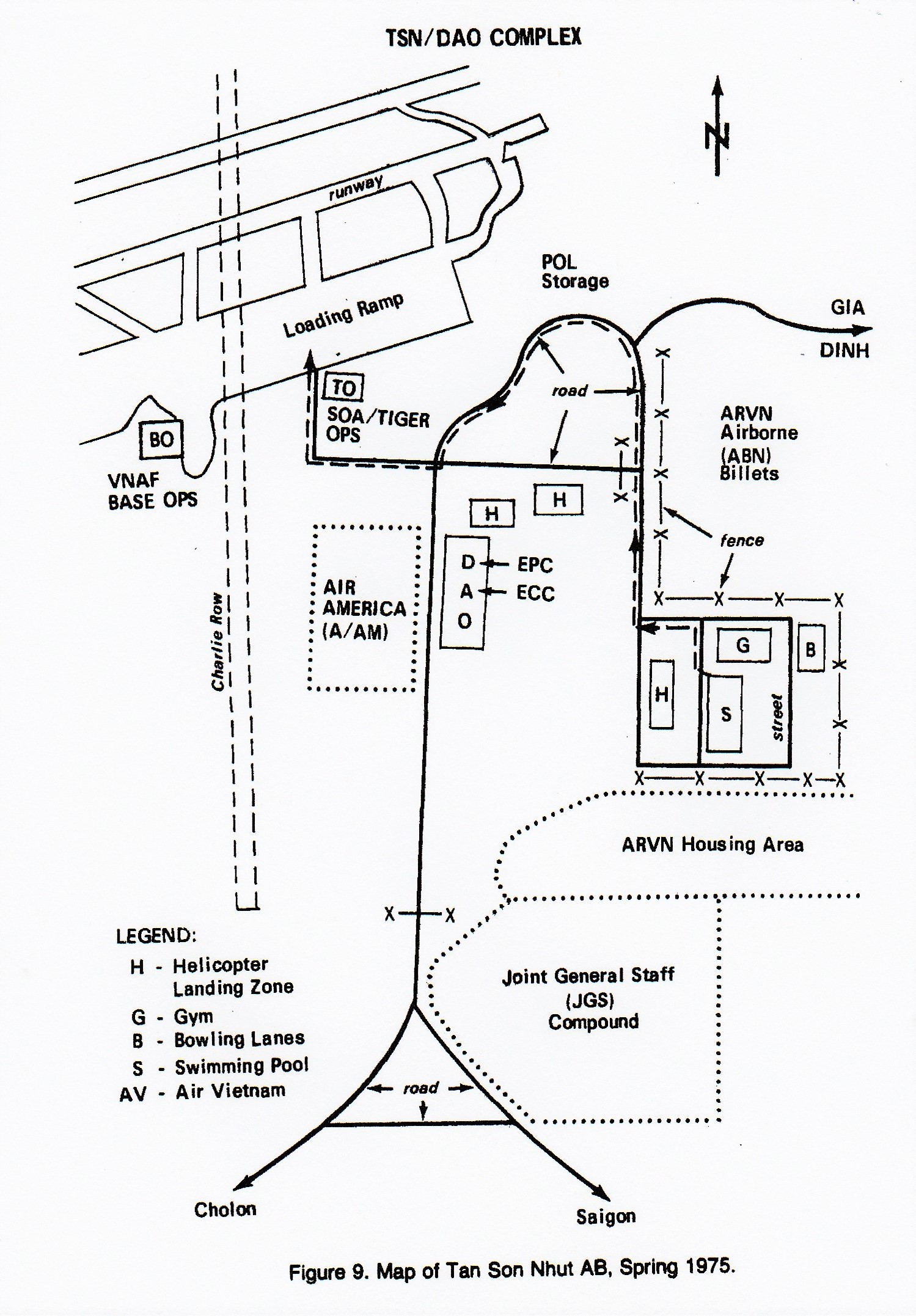

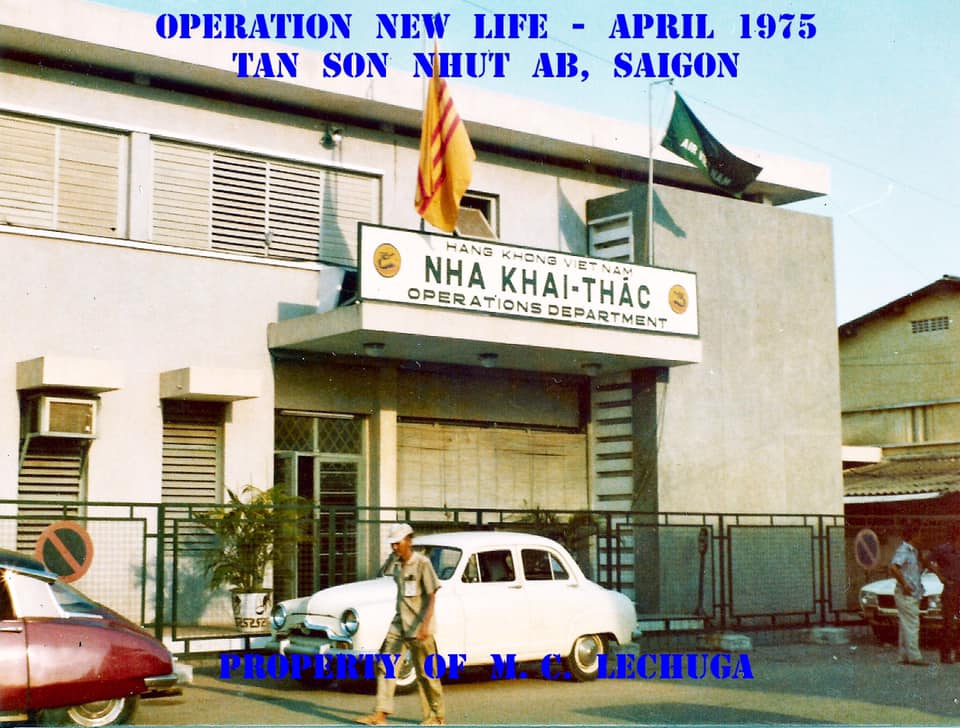

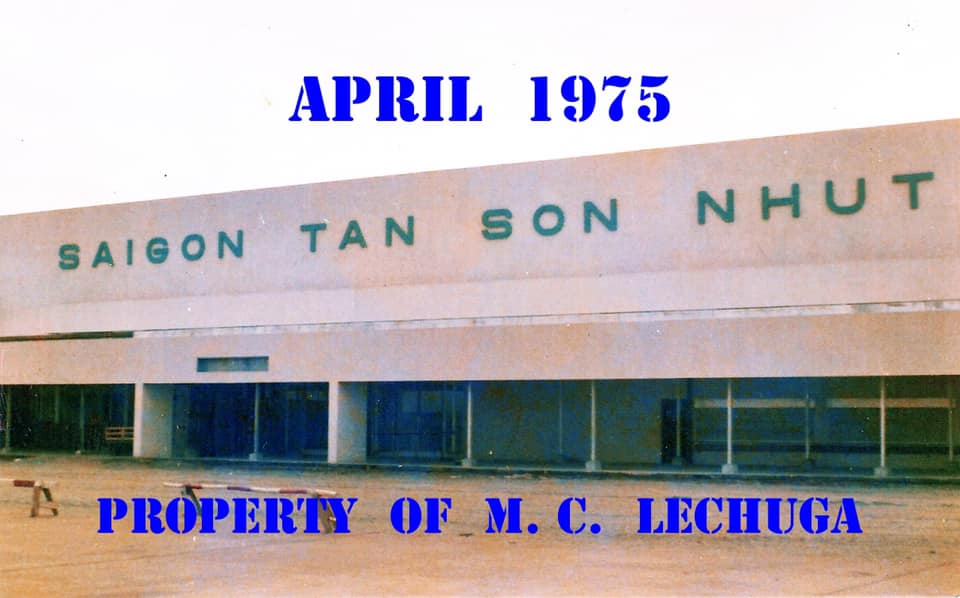

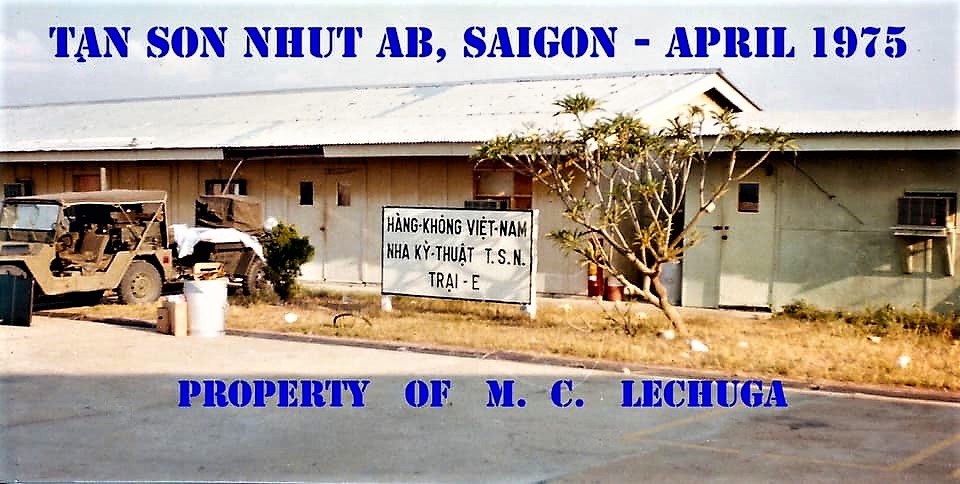

The USDAO was located in the old Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) headquarters building on Tan Son Nhut Airport (aka Pentagon East).

The Case–Church Amendment legislation was approved by the U.S. Congress in June 1973 and prohibited further U.S. military activity in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia without Congressional approval. This included air support. And Congress never did approve additional aid to meet the NVA offensive. This pretty much doomed South Vietnam to the onslaught of the Soviet/Chinese supplied North Vietnamese. It was only a matter of time before South Vietnam fell under the weight of the well-supplied North Vietnamese and the corruption within the South Vietnamese government.

The final North Vietnamese invasion, Campaign 275, started in the winter of 1974 and began to snowball after some strategic mistakes by the South Vietnamese government in March 1975. The rapid collapse of South Vietnamese defenses resulted in a more ambitious NVA objective: the capture of Saigon before the birthday of Ho Chi Minh on May 19, 1975. North Vietnam changed the name of Campaign 275 to the “Ho Chi Minh Campaign.”

The main problem facing the United States was to how to get her citizens and at-risk loyal South Vietnamese out of the country. An impossible task in the time allowed when you look at it in retrospect. To say it was not planned well is an understatement. But, it was something that had to be done. With the North Vietnamese Army rolling down their coastline, there was still not a sense of urgency in Saigon to get people out of the country.

In late March, the Military Airlift Command aircraft were arriving in Saigon at a rate of two or three each day. Ground handling of these aircraft were handled by the USDAO’s Supervisor of Airlift flight line crew. The Supervisor of Airlift contingent’s main duty was to manage the civilian contracted ricelift to Cambodia.

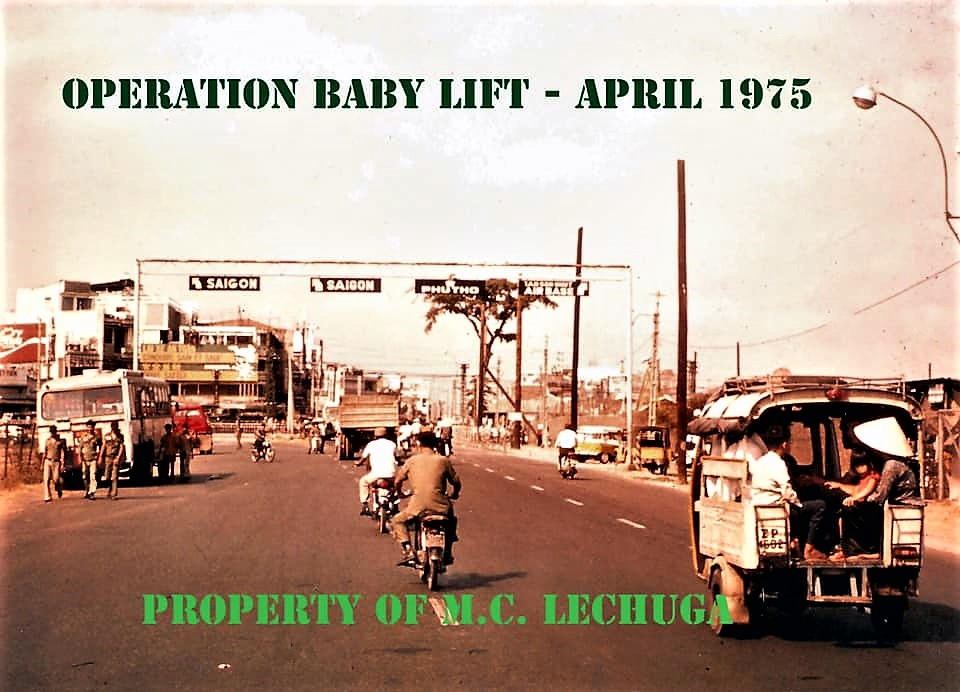

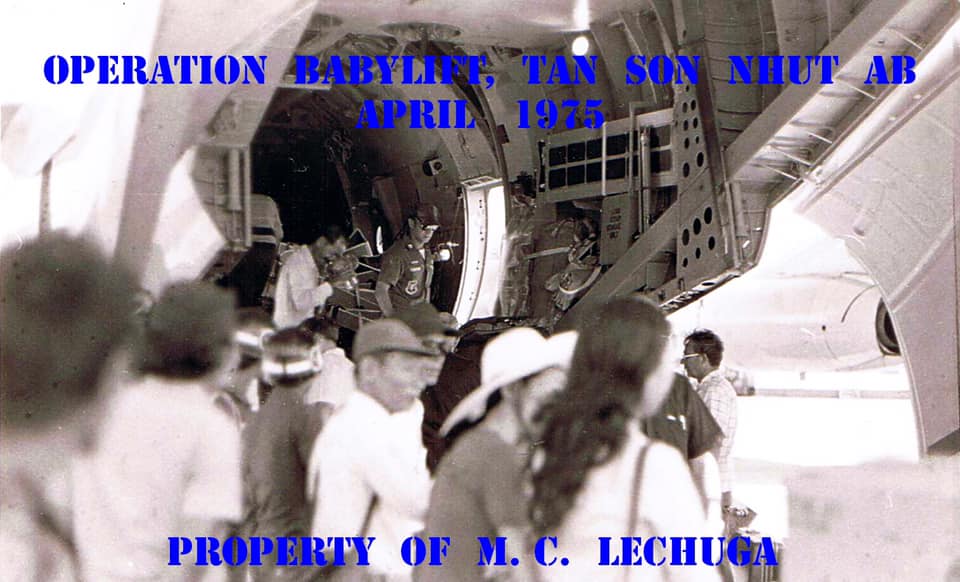

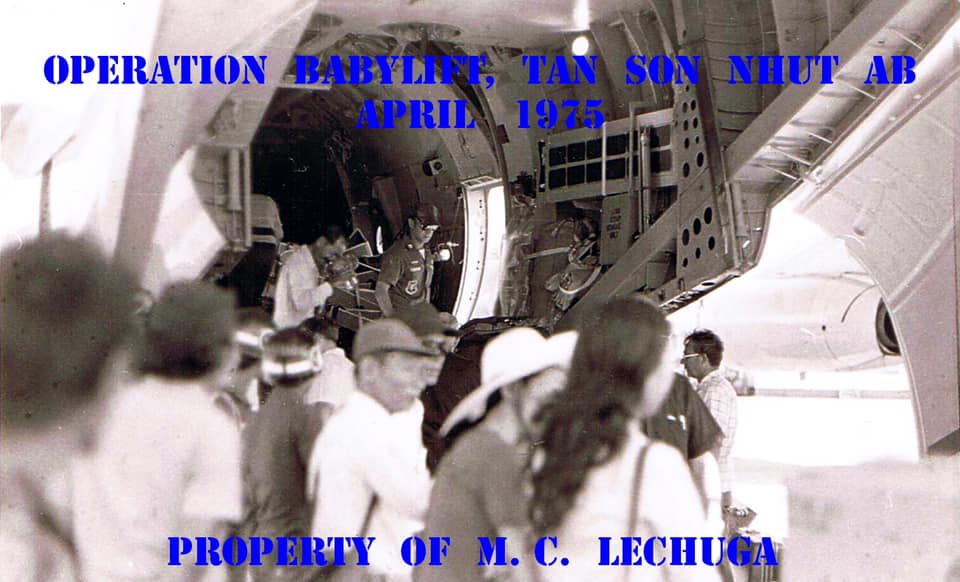

During the first few days in April, as the number of USAF cargo aircraft increased, the Supervisor of Airlift also became involved in the “Babylift” of Vietnamese orphans which was getting increased emphasis from both the Departments of State and Defense.

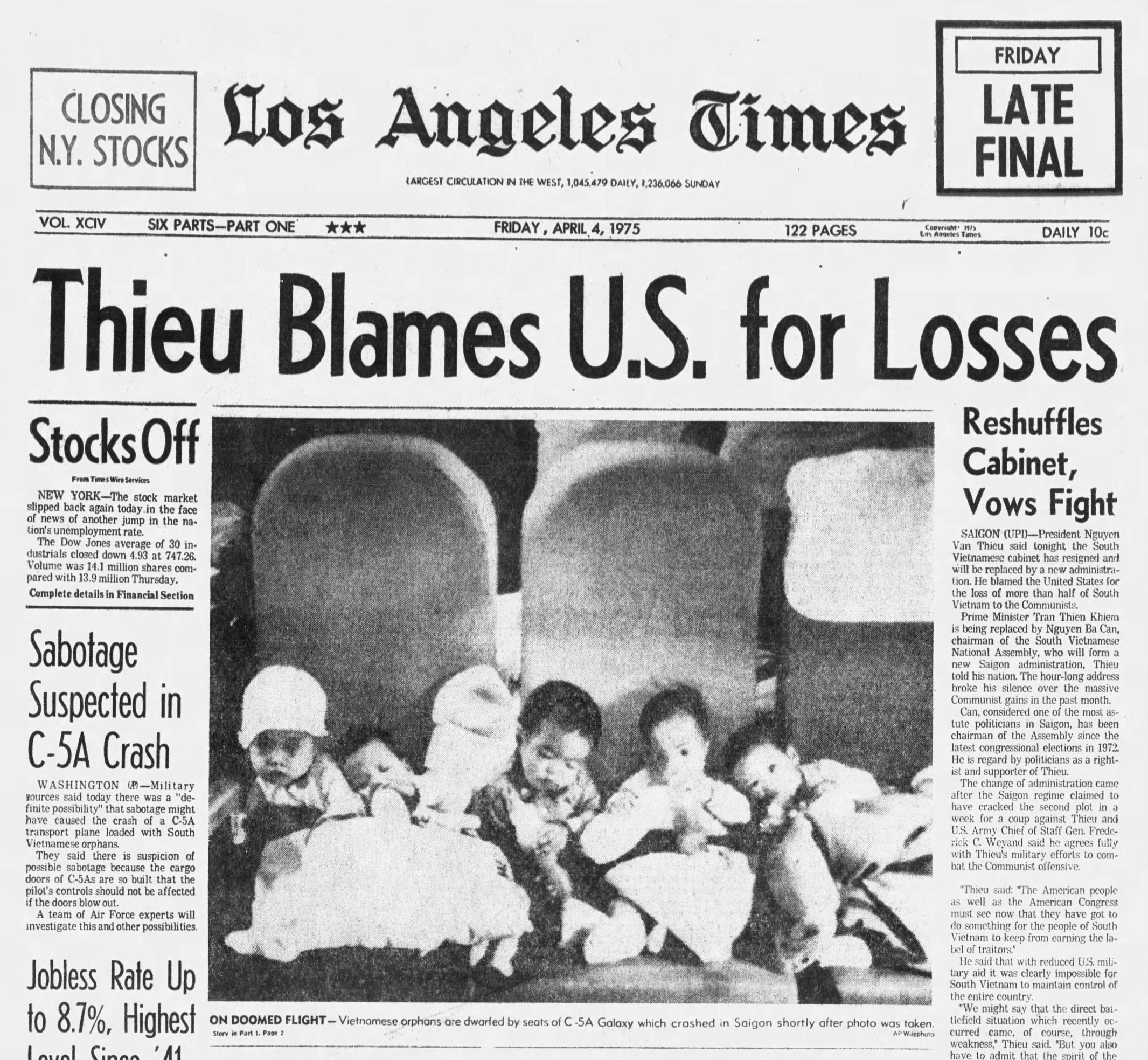

If there was one defining moment that signaled the start of the mass exodus, it was the crash of the C-5 carrying Vietnamese orphans out of Saigon on Friday, 4 April 1975

With the projected increase in US military flights into Saigon to evacuate orphans and US personnel, additional USAF members would be needed to assist in the ground handling of aircraft and processing of passengers. Shortly after the crash of the C5, the USAF issued a call for volunteers at Clark AB to go to Saigon to work the airlift aircraft in the growing evacuation flights of Americans from Saigon, Vietnam.

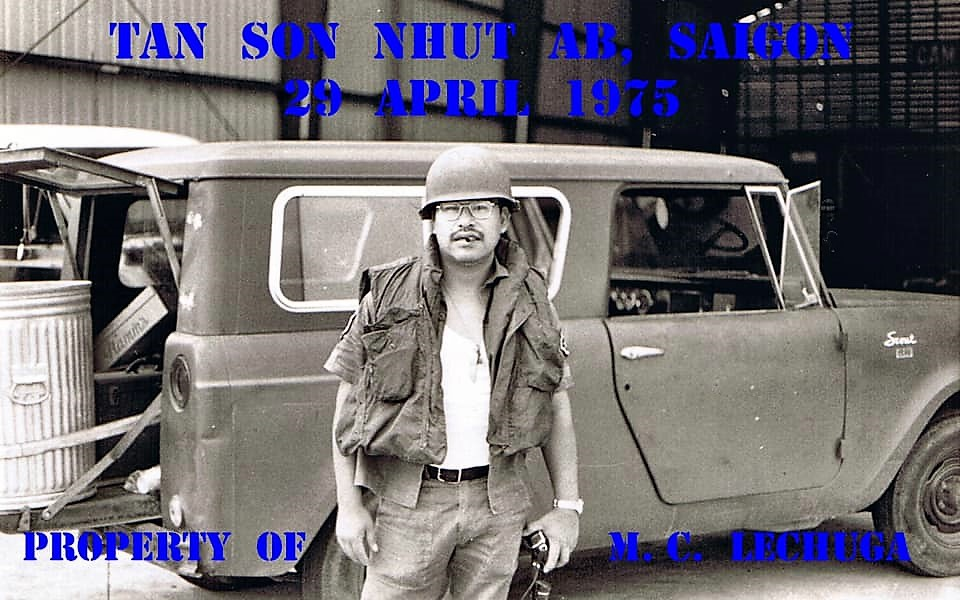

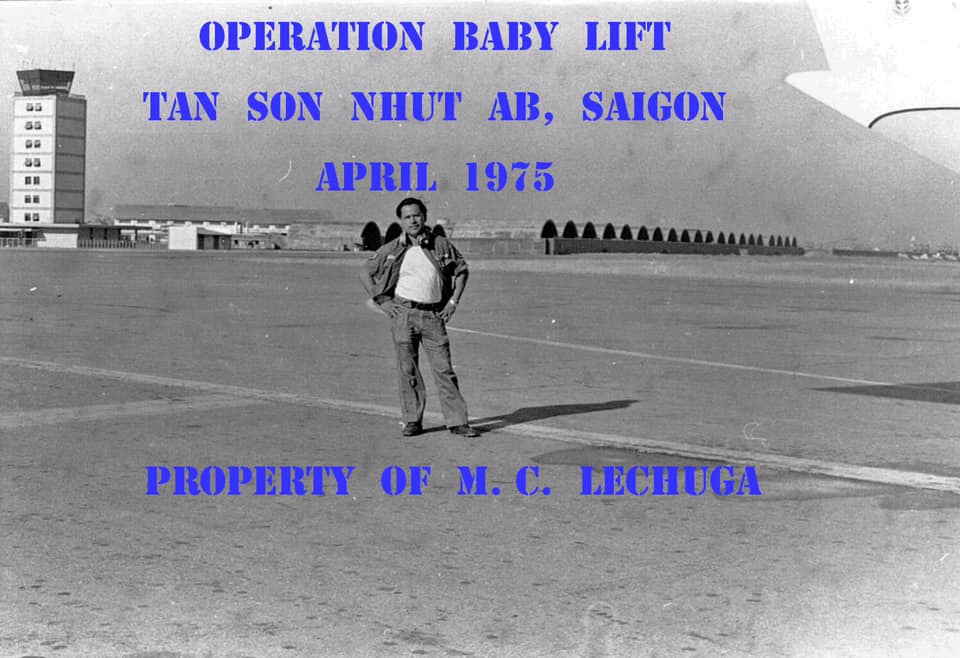

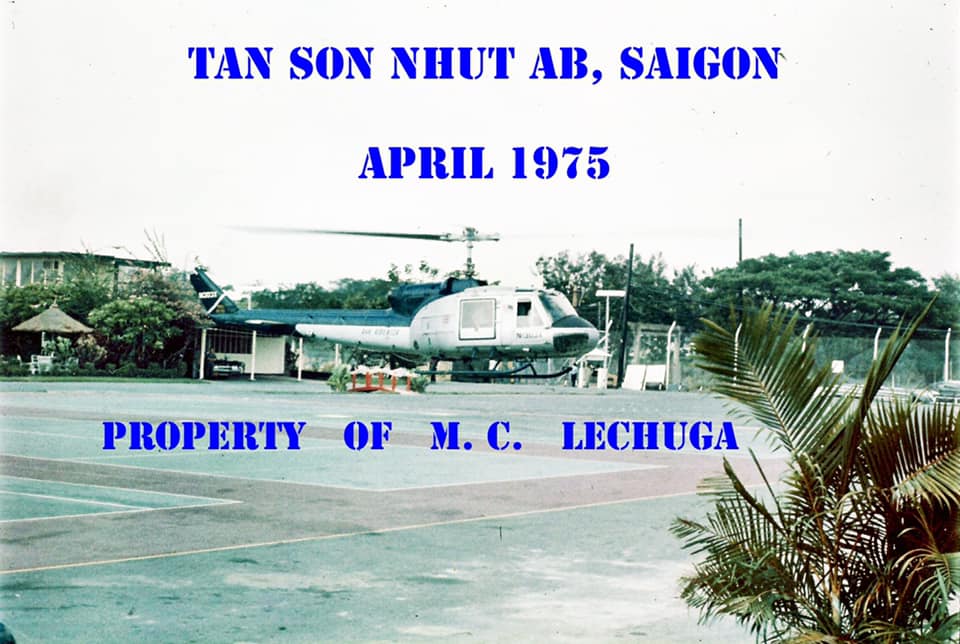

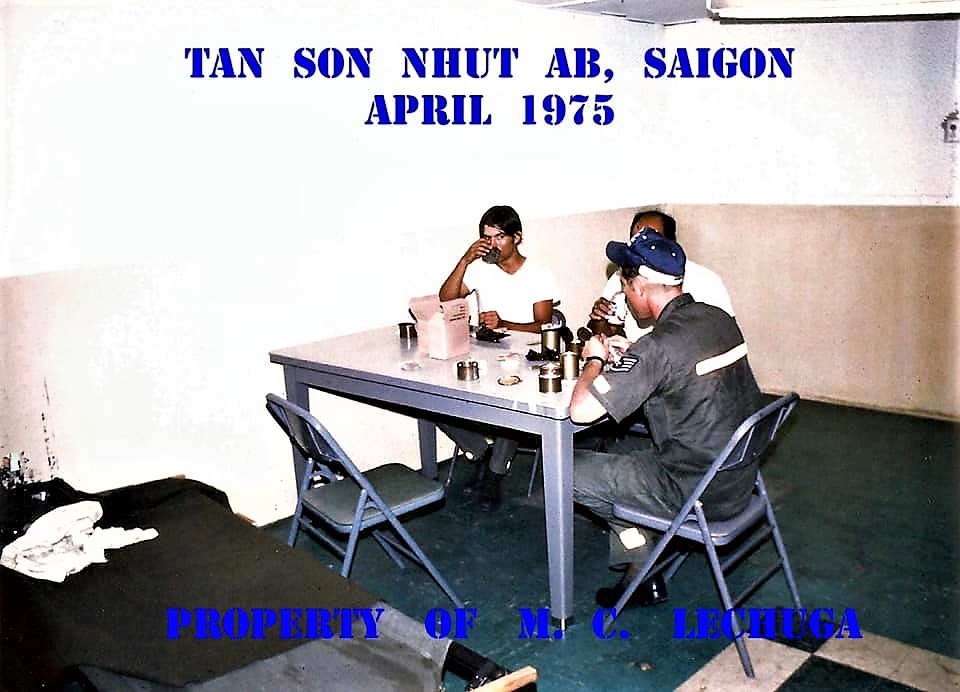

SSgt Lechuga was one of the first to volunteer for this duty. He would end up spending 23 days at the busy Tan Son Nhut Air Base and would be a witness to the last days of South Vietnam. He took his camera with him and has documented those last days in Saigon with an incredible number of historical photographs. We start his story at Clark AB in the Philippines, a few days prior to leaving for Vietnam.

4 April 1975 – Friday at Clark AB, Philippines_______

“It was a normal work day. The temperature was hot and humid, as were most days at Clark Air Base, located in the Republic of the Philippines. Our unit, the 604th Military Airlift Support Squadron (MASS), was a Military Airlift Command (MAC) tenant unit, under the command of the 6200th Air Base Wing, the host unit.”

“At the time, I was a Staff Sergeant avionics instrument systems specialist. Our unit’s mission, was to provide ground aircraft maintenance support for any transiting military aircraft stopping for any length of time, at Clark AB. Most of our aircraft traffic were MAC jet cargo aircraft, such as the C-141 Starlifter, and the C-5 Galaxy. Their missions originated and terminated at their home base in the Continental United States (CONUS), and they transited/stopped at Clark on their way and return from the Far East region. The time spent at Clark varied depending on the reason for the stop—off load/pick up cargo, off load/pick up passengers (PAX), a two-hour quick-turn (refuel, repair, load/off load pax/cargo, and launch), or remain overnight (RON) for crew rest. A variation of the stop time is when we had a problematic maintenance problem, a hard-break, which grounded the aircraft, until the malfunction was fixed.”

“On 4 April 1975, aircraft traffic seemed normal, nothing appeared to be out of the ordinary. We had a C-5, Tail # 68-0218, affectionately called Fat Albert by maintenance troops, on the ramp and routine maintenance operations were in progress. The C-5 was the largest jet cargo aircraft in the United States Air Force (USAF) inventory. It had a cavernous main cargo deck, which could easily hold six Greyhound passenger buses; the top forward section had the crew cockpit area and a bunk area for crew rest, and the top aft section had an ample passenger section. Both, the forward crew area and the aft pax section, were accessed by permanently affixed, foldable and stowable, aluminum ladders. During the aircraft’s launch preparation, I remember climbing the front ladder, to the aircraft’s cockpit area, and casually glancing at the cargo deck and seeing about six armored personnel carriers (APC), plus other ordnance. We knew the aircraft was headed for Tan Son Nhut, Air Base, Republic of South Vietnam (RSVN), and we understood we were sending military support to South Vietnam, even as the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) was relentlessly marching towards the South Vietnamese Capitol of Saigon. My good friend, Staff Sergeant George Cadarette, an aircraft electrician, worked a cockpit windshield heat problem on the aircraft, and he distinctly remembered the event until his death, last year, from prostate cancer due to Agent Orange exposure during a tour at Cam Ranh, Air Base, RSVN, prior to 1975.”

“Finally, the aircraft was ready to launch on its mission: the fire guards were posted, the engines started, the aircraft crew chief performed a visual inspection of the airframe, he gave the hand signal for the landing wheel parking chocks to be pulled, he climbed on board, the crew entry door closed, and the aircraft blocked (left its parking spot). Anyone who has worked on or been around C-5 aircraft, remembers the distinctive high-pitched sound of the four TF-39 (Turbo Fan) jet engines, the massive size of the aircraft as it maneuvers during taxi, and how it appears to slowly float into the air, as if by magic. It was a normal work day, a normal aircraft launch, like many others we had done before. After its departure, we continued to work on other aircraft at Clark.”

“Later in the day, we heard the news, – the aircraft had crashed on take-off from Tan Son Nhut. Our unit was stunned and saddened by the tragic news, the loss of life—4 April 1975, will forever be etched in our hearts.”

6 April 1975 – Monday__________________________

“Soon after the C-5 crash, my shop chief at Clark AB asked me if I still wanted to deploy to Saigon, on an open-ended TDY. My reply, “When do I leave?” Next day, I’m part of an aircraft maintenance team, at Tan Son Nhut AB, providing ground support for Babylift aircraft.”

HISTORICAL NOTE: By the beginning of 1975, it was determined a fairly stable figure of 8,000 Americans and Third Country Nationals would need evacuation. But there never was a firm figure for the number of Vietnamese to be carried out. Estimates varied from 1,500 to 1,000,000 Vietnamese who had been so closely associated with the US that their lives would be endangered under a Communist regime. President Ford gave a speech that reinforced and confirmed Ambassador Martin’s public promise to evacuate all US mission employees and their families,

since some in Saigon believed that leaving them behind would be abandoning them to the conquering North Vietnamese. There were approximately 17,000 employees on the Mission rolls which, using an average of seven members per family, equated to 119,000 Vietnamese to be evacuated. When other categories of Vietnamese to whom commitments were made were included, the total quickly ballooned to approximately 200,000. On I April 1975, the USDAO had established the Evacuation Control Center at Tan Son Nhut AB. It opened on a 12-hour day shift, but went to a 24-hour schedule the next day. The officers and civilians of the Defense Attache’s Office were supplemented by four ground radio operators from the 1961 st Communications Group, USAF, Clark AB, Philippines. They requested and got additional help in processing passengers: 11 security guards, one customs official, and eight maintenance specialists for the processing of evacuees and the flight line operation of the C-141s. In addition, two USAF officers from the Aerial Port of Clark AB, were assigned to supervise the aircraft unloading of supplies and loading of passengers. (USAF MONOGRAPH 6, Last Flight From Saigon )

7 April 1975 – Monday__________________________

“We boarded a C-141 that morning at Clark AB and flew directly to Tan Son Nhut AB in Saigon. Arriving that afternoon we received a quick briefing on the situation from SMSgt Gerald (Jerry) Shaw. We went right to work providing support for the evacuation aircraft. After the end of the shift that evening we were sent to the Defense Attache Office (DAO) Annex for billeting arrangements, which would be located off base.”

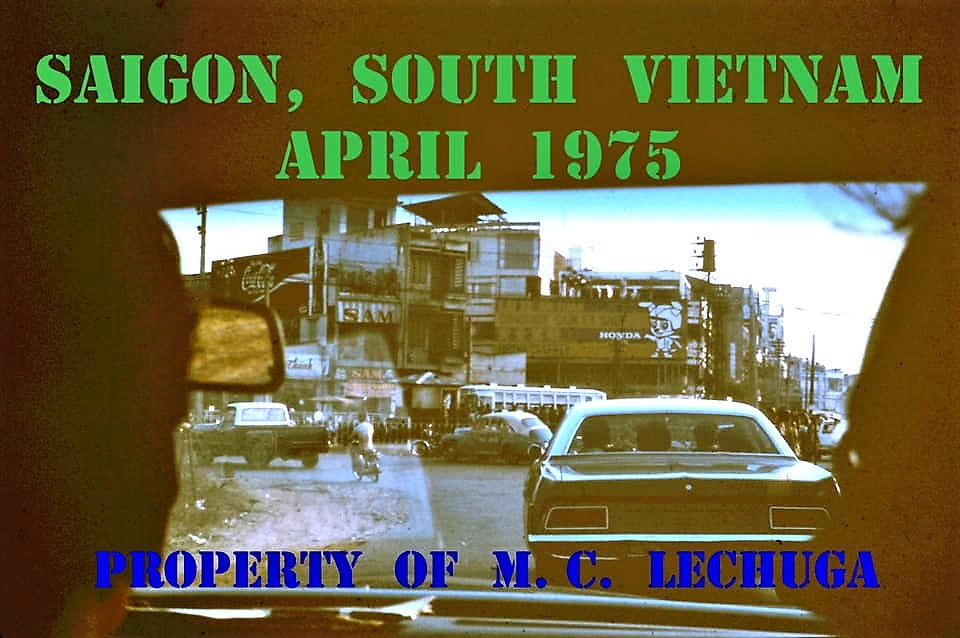

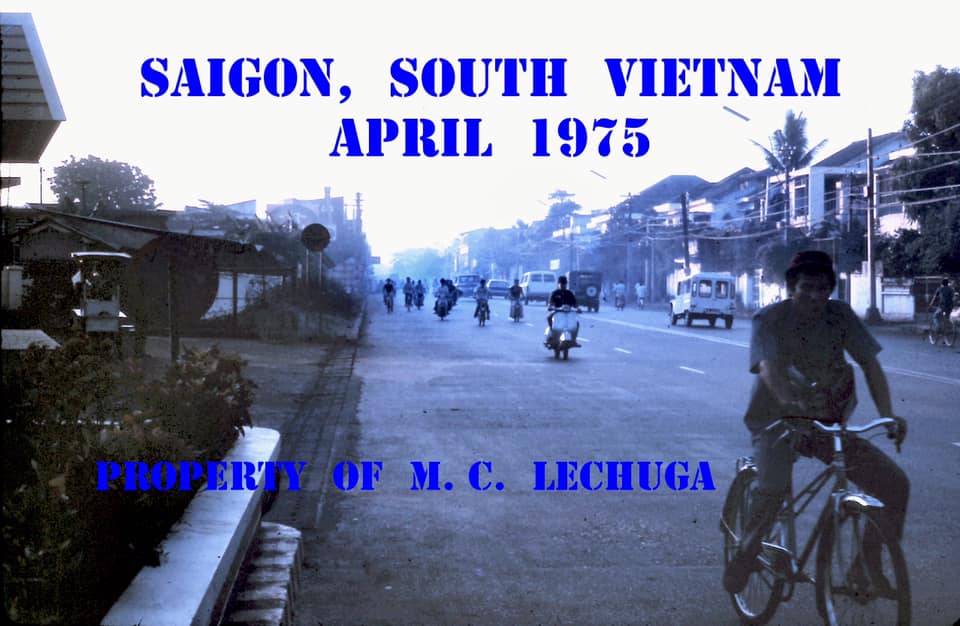

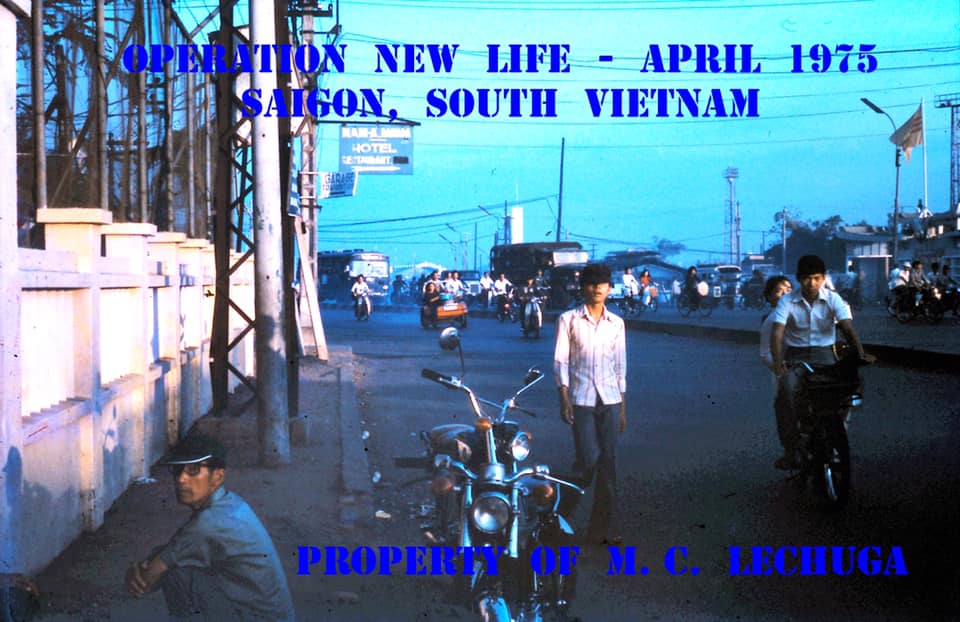

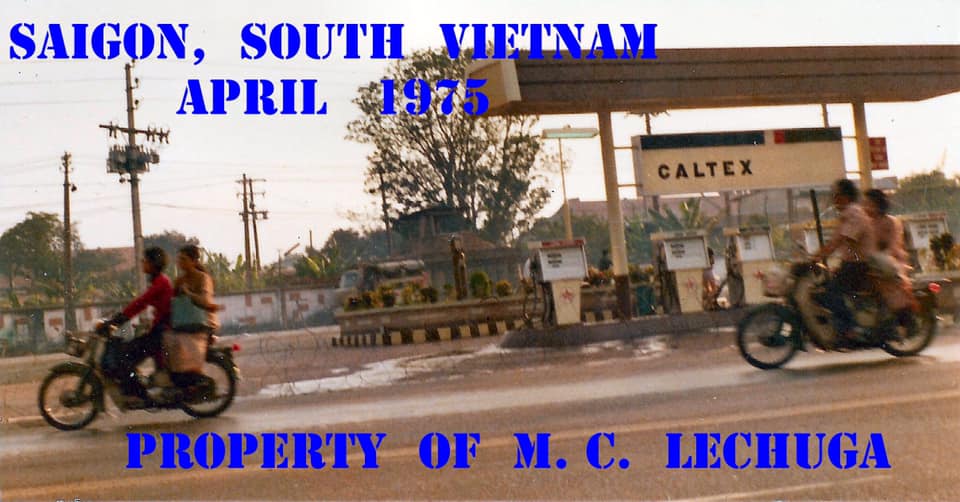

“We leave Tan Son Nhut AB for our quarters off base. In our spare time, we got to visit parts of Saigon. The war had not reached Saigon yet.”

“The Babylift C-141 aircraft were flying daytime missions only, so after our 12-16 hour day ended, we returned to the DAO Annex for the night.”

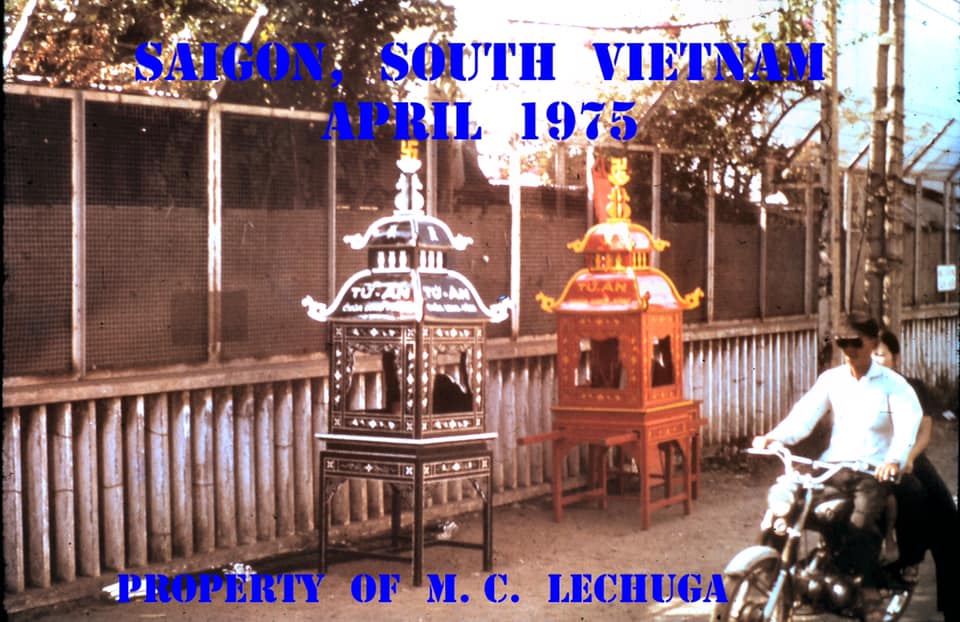

“Although there was a 2300-hours curfew, we were not under any movement restrictions; therefore, we toured the sights of Saigon and became acquainted with messieurs Ba Moui Ba and Larue. Besides the ceramic Elephants at the Tan Son Nhut Base Ops, there was a good opportunity to buy brass as you can see on the right side of the picture. Note the reflective tape on the peace time USAF uniform. I would later turn my shirt inside out to hide the reflective tape so as to not become a target.”

9 April 1975 – Wednesday________________________

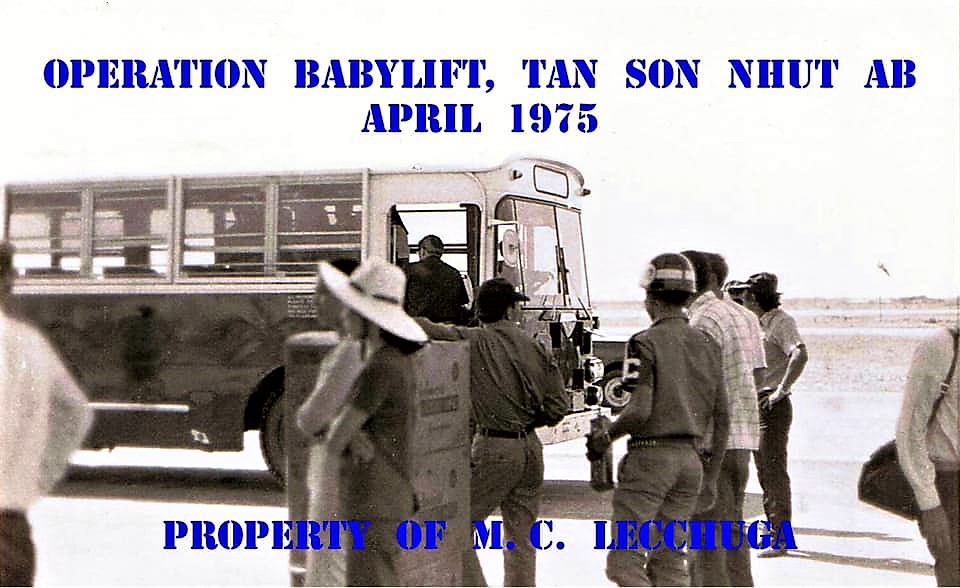

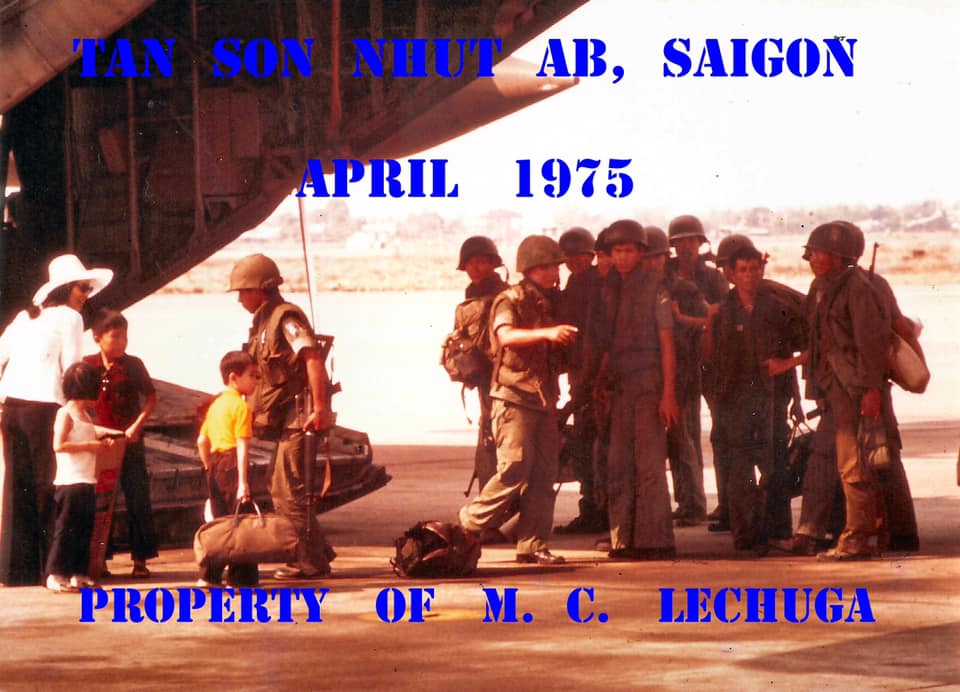

“The C141s and C130s arrived at scheduled intervals and passengers were processed normally by the passenger terminal. Customs cleared them and their bags were loaded onto the back of the aircraft for their trip out of Vietnam. There was no rush and everything was routine.”

HISTORICAL NOTE: On this date 50 miles north east of Saigon, the battle of Xuân Lộc began, the last ditch effort of the South Vietnamese to stop the drive of the NVA toward Saigon.

“Loading of the precious cargo; next stop, Clark AB.”

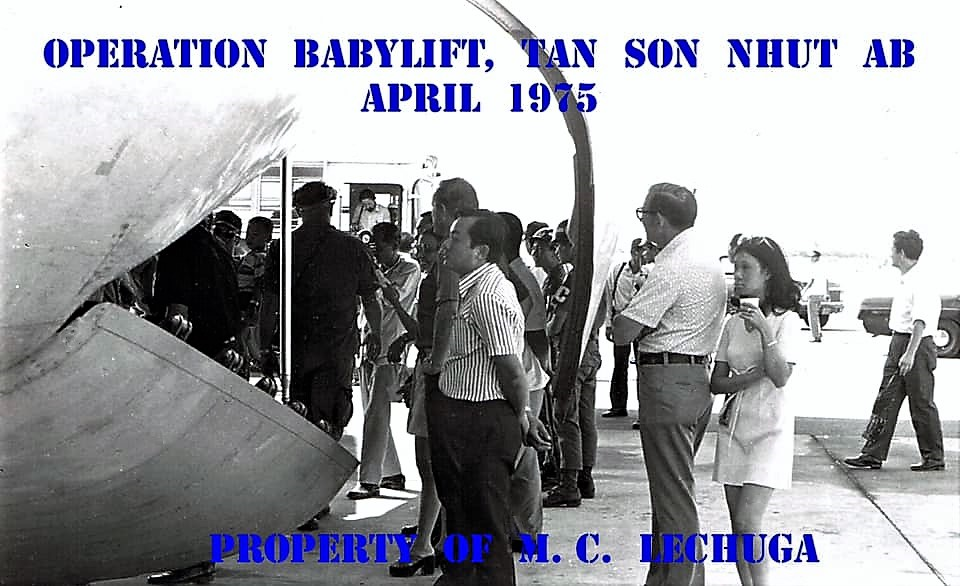

“Loading orphan children on the C141. There was no sense of urgency. “ (Lechuga Photo)

“These photos show the normal aircraft passenger loading operation on the flight line. I took a photo of the base passenger terminal, but our pax were processed at the DAO Compound, former MACV Headquarters, then transported by bus to the aircraft.”

THE CALM BEFORE THE STORM . . . . . .

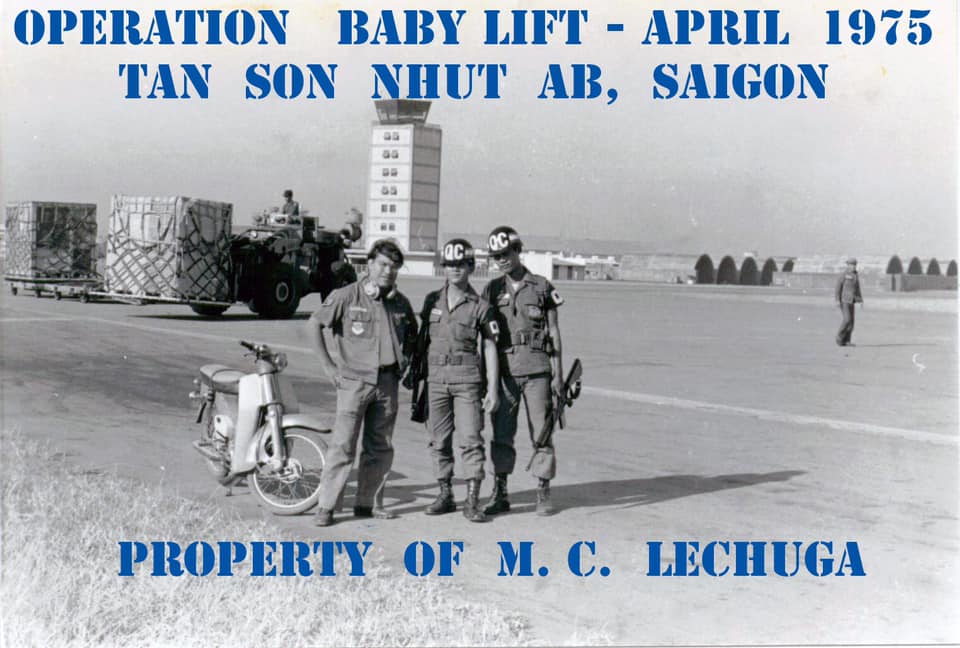

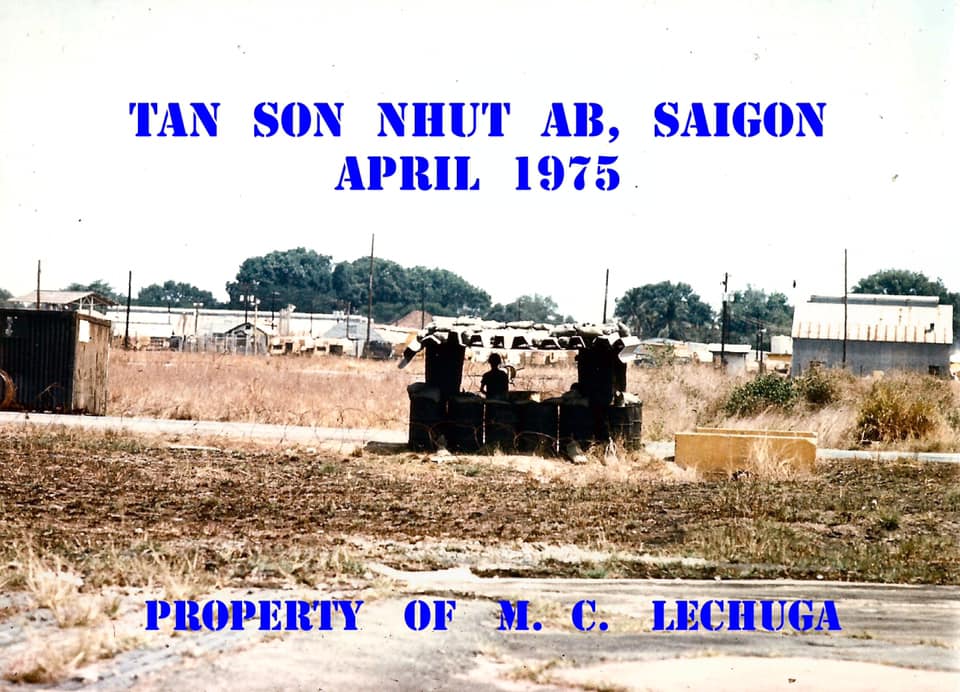

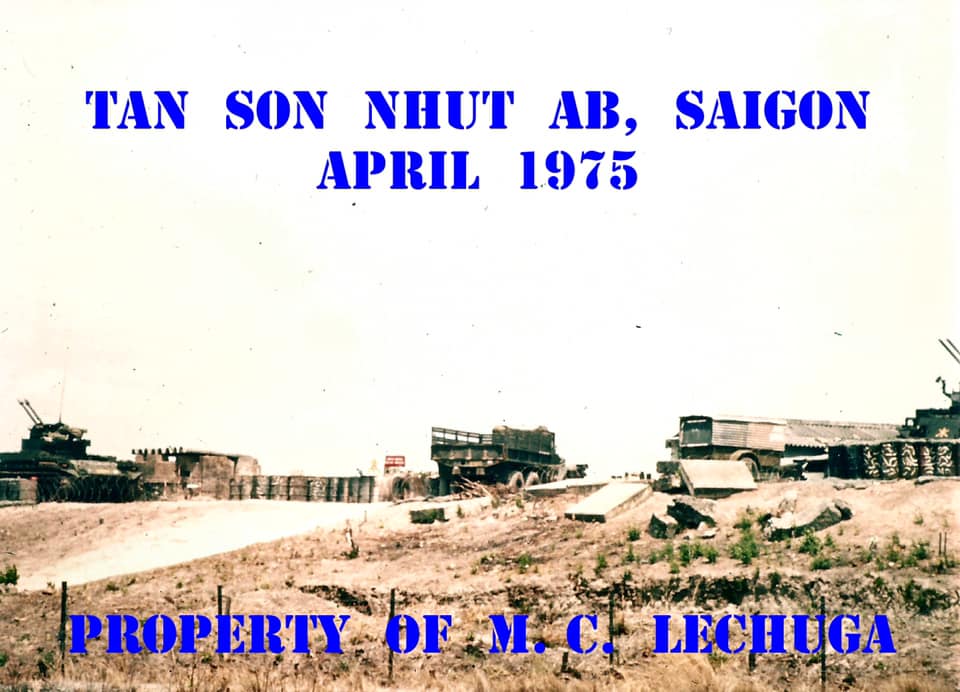

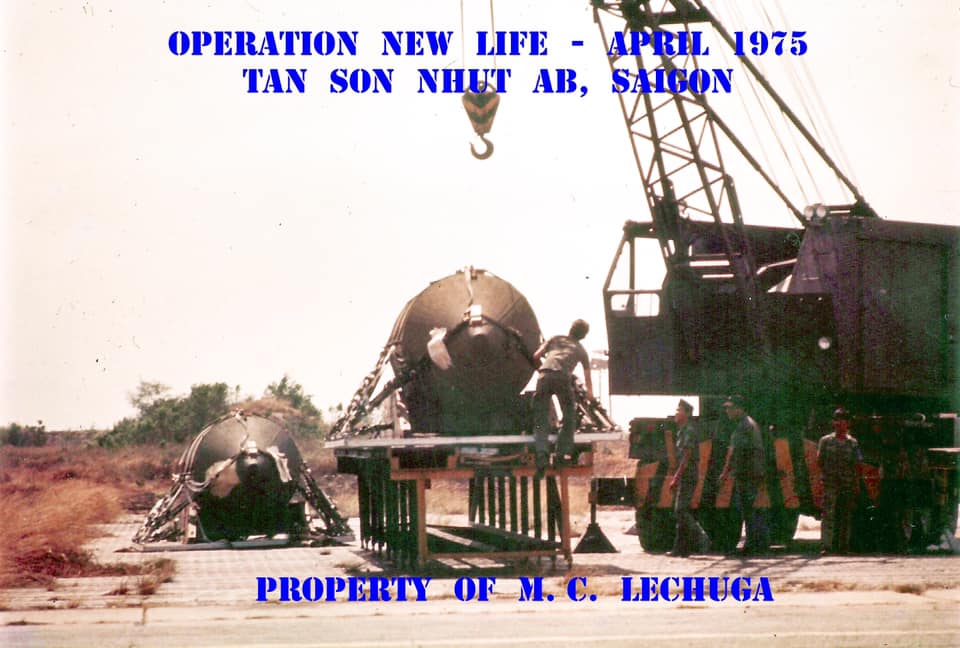

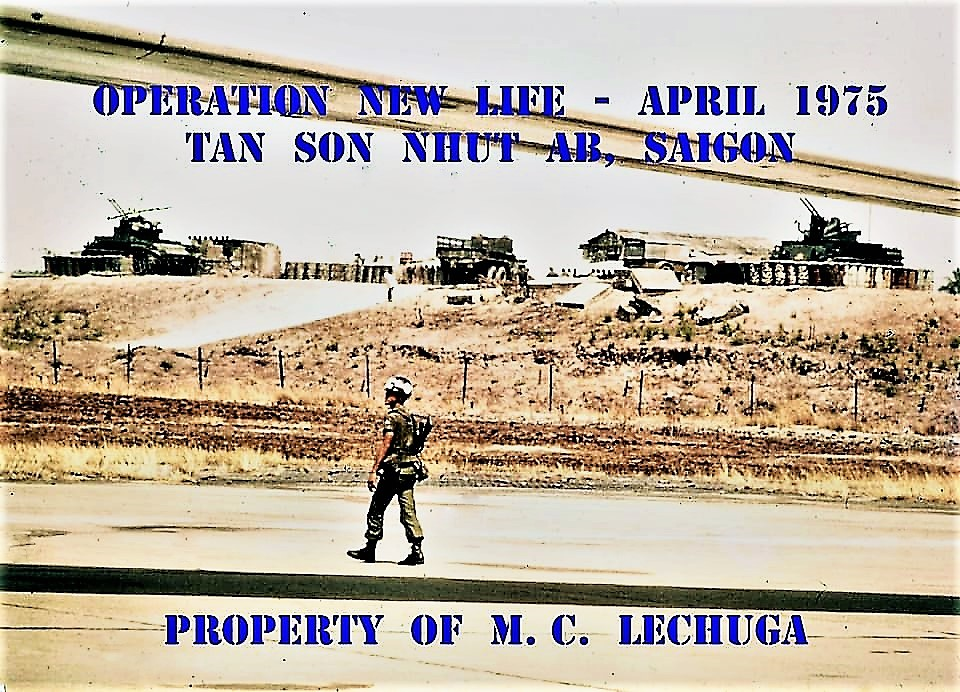

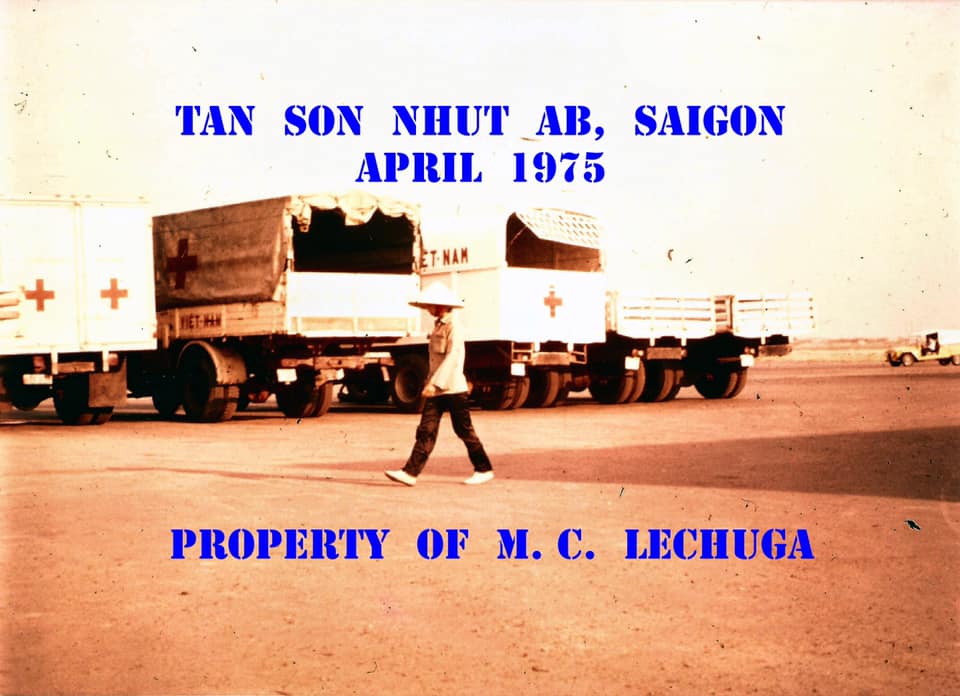

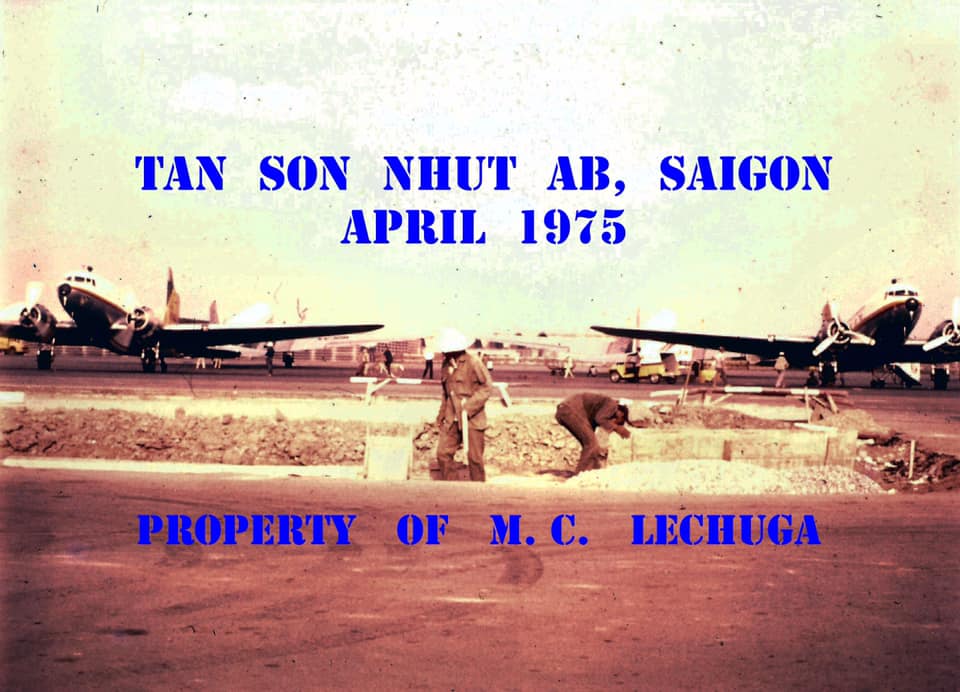

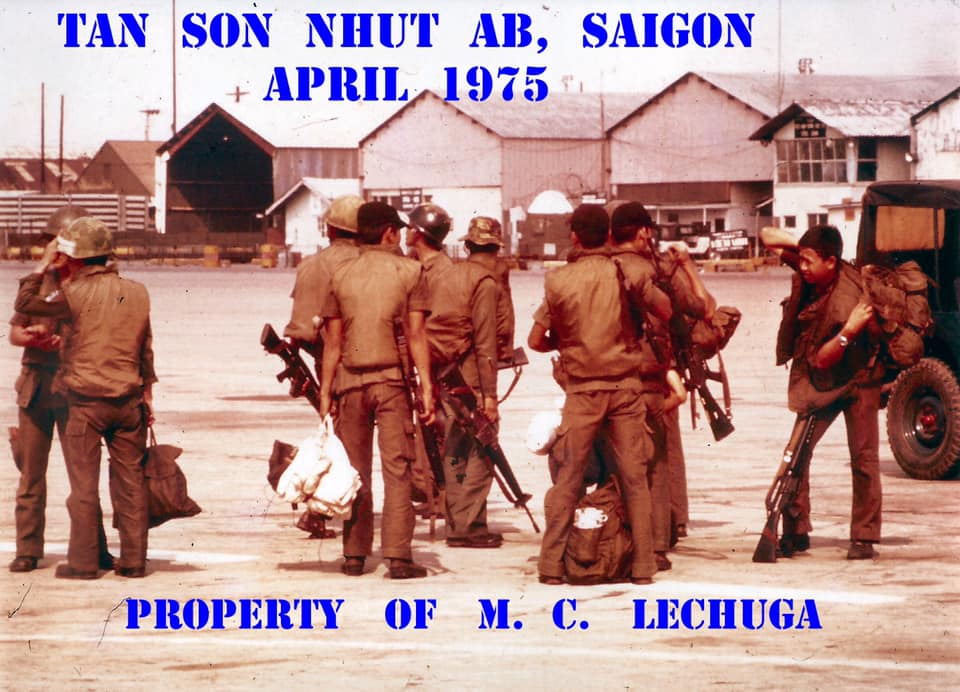

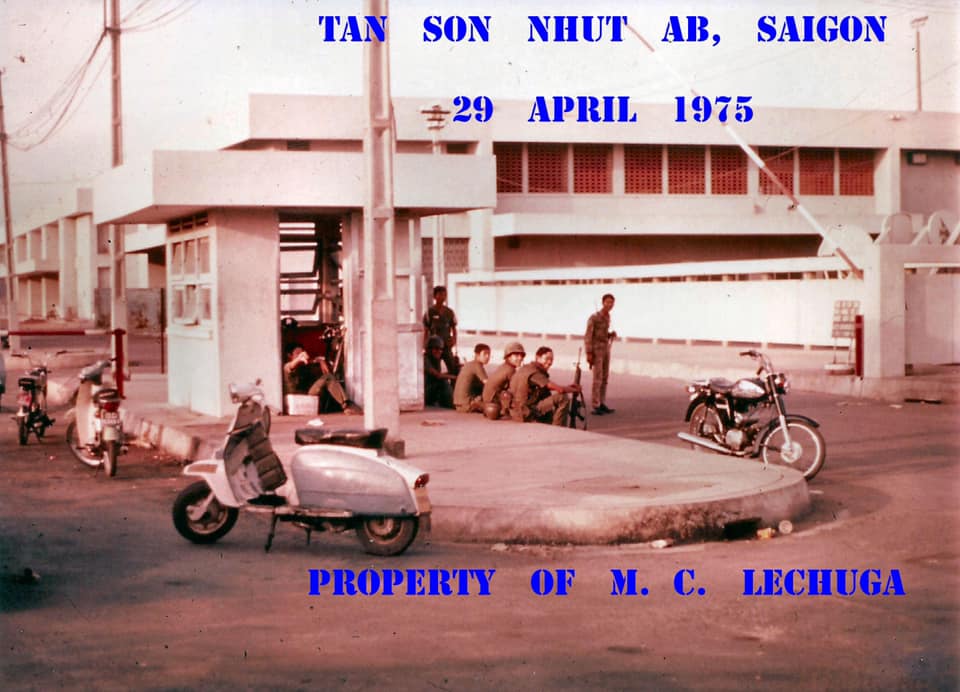

“These photographs were taken in between working evacuation flights. The NVA were getting closer to Saigon, yet operations at the base appeared normal. Guards were at their posts, perimeter defensive bunkers and anti-aircraft positions were manned, aircraft maintenance continued, ordnance was being delivered, and aircraft sorties flown. Soon this would change.”

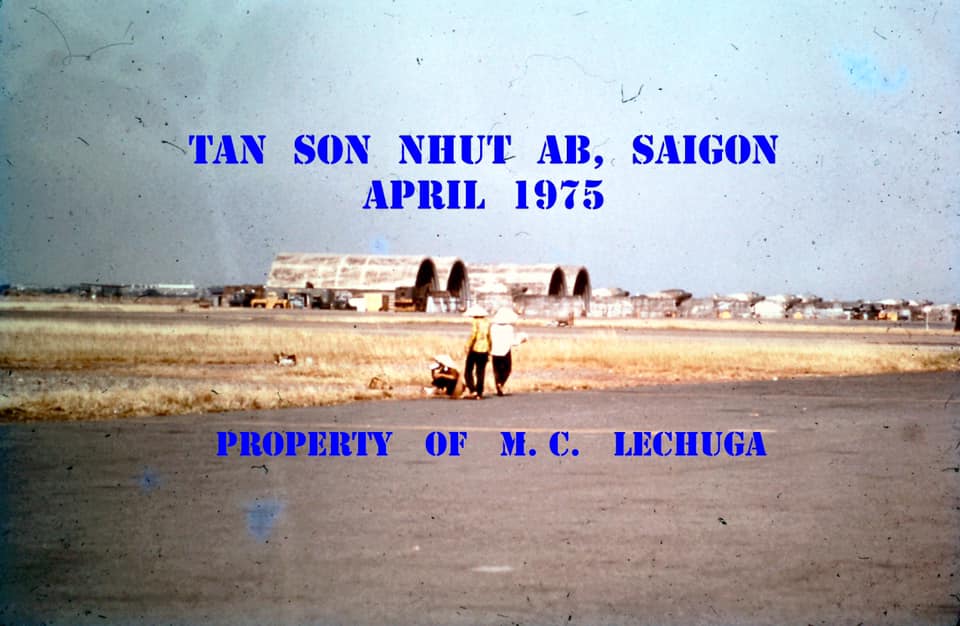

“Two South Vietnamese private hire guards at a checkpoint on Tan Son Nhut AB. Most were retired ARVN soldiers and did not carry weapons” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga photo)

“Bunker on the perimeter of the base.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

“South Vietnamese anti aircraft guns beside the flight line.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

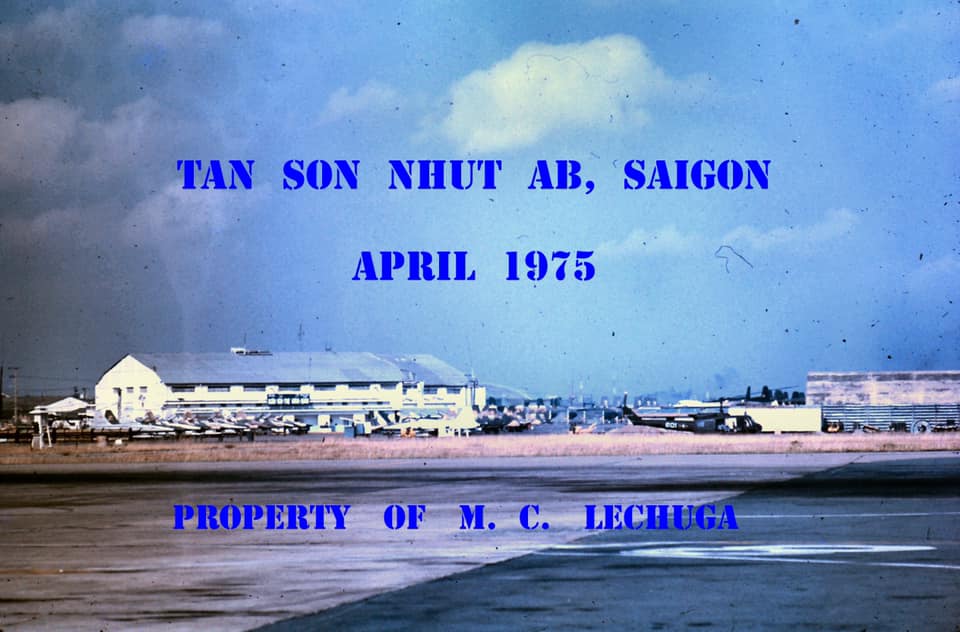

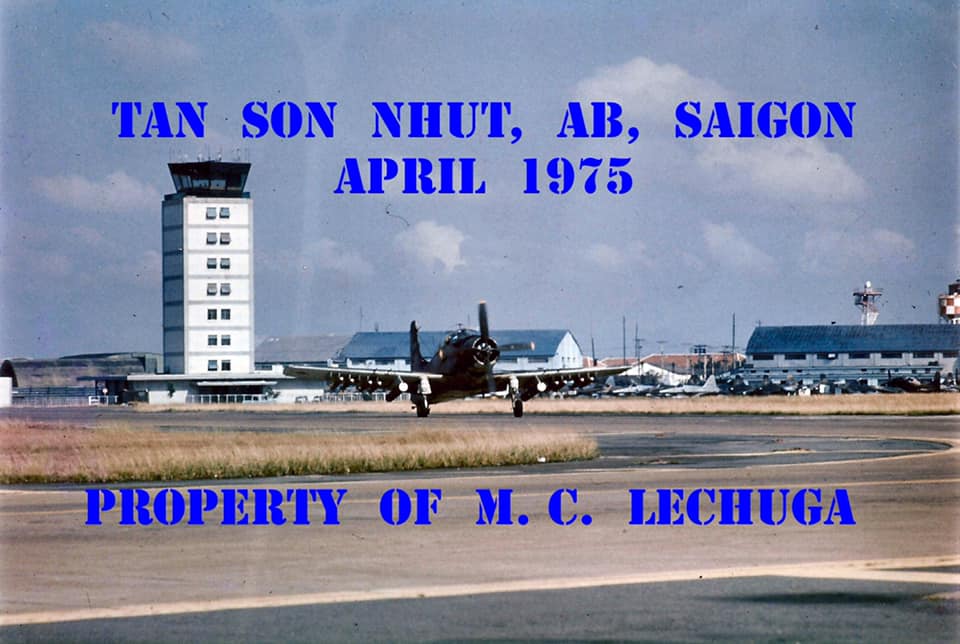

“Tan Son Nhut Base Opertaions, home of the Saigon Elephants.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

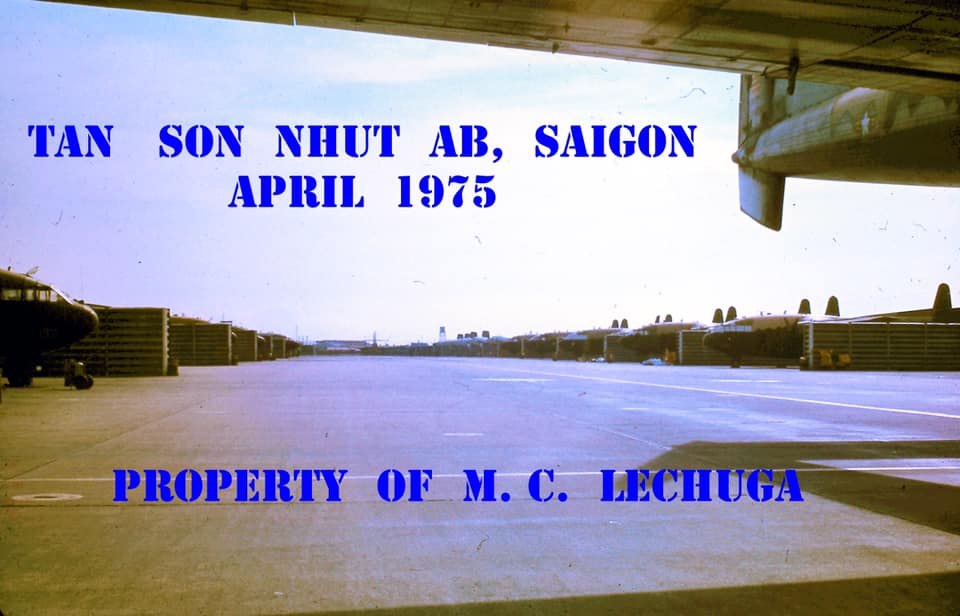

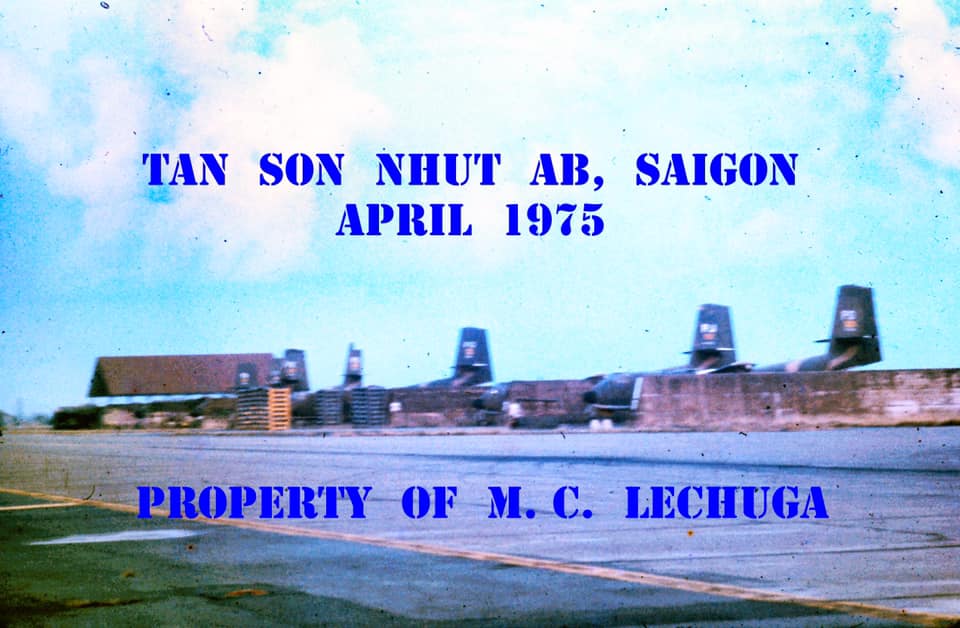

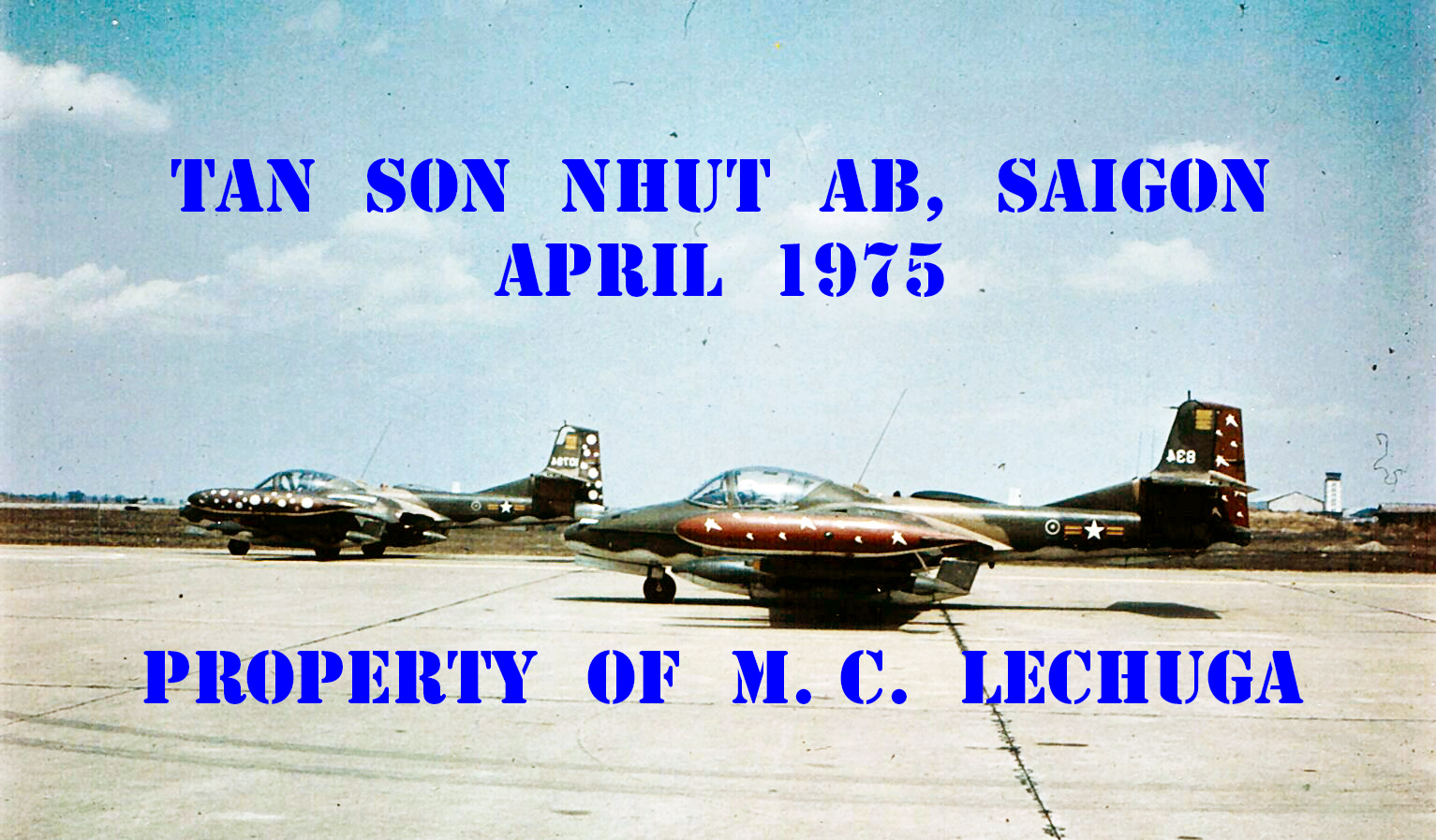

“AC119 gunships.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

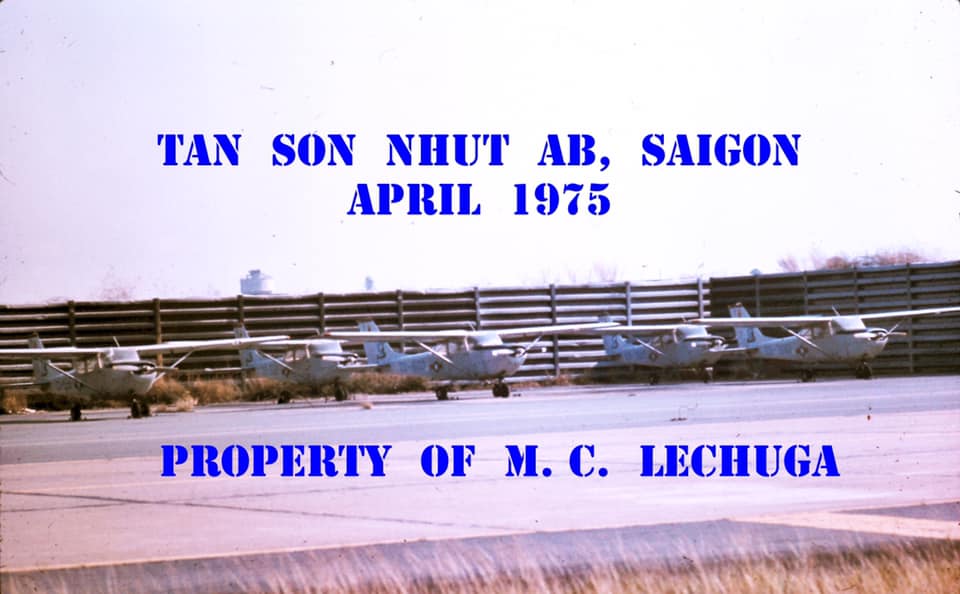

“T-41 trainers parked in a revetment. “ Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

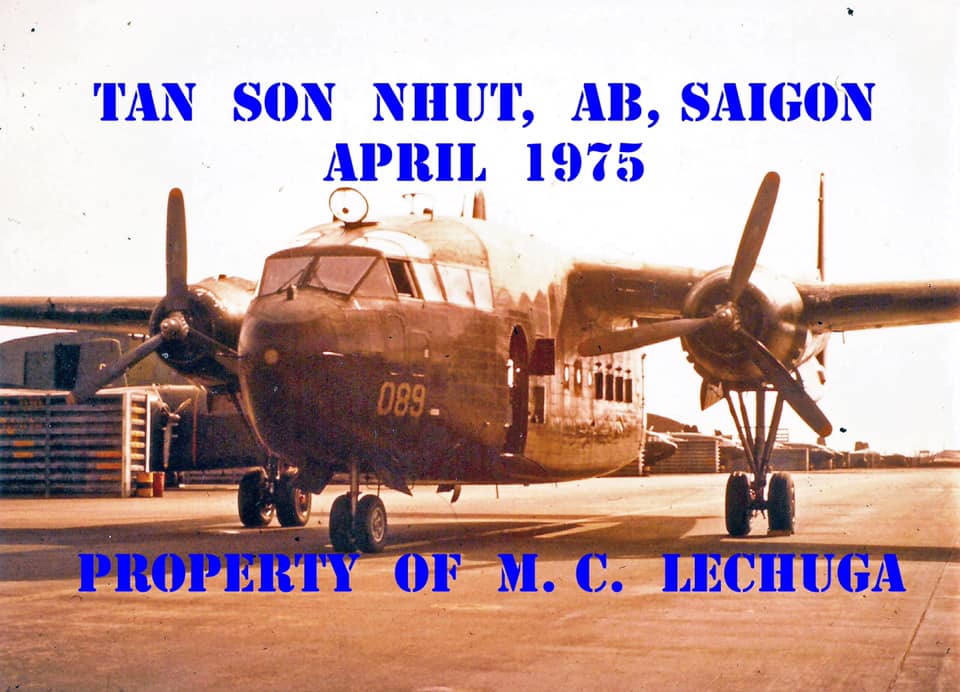

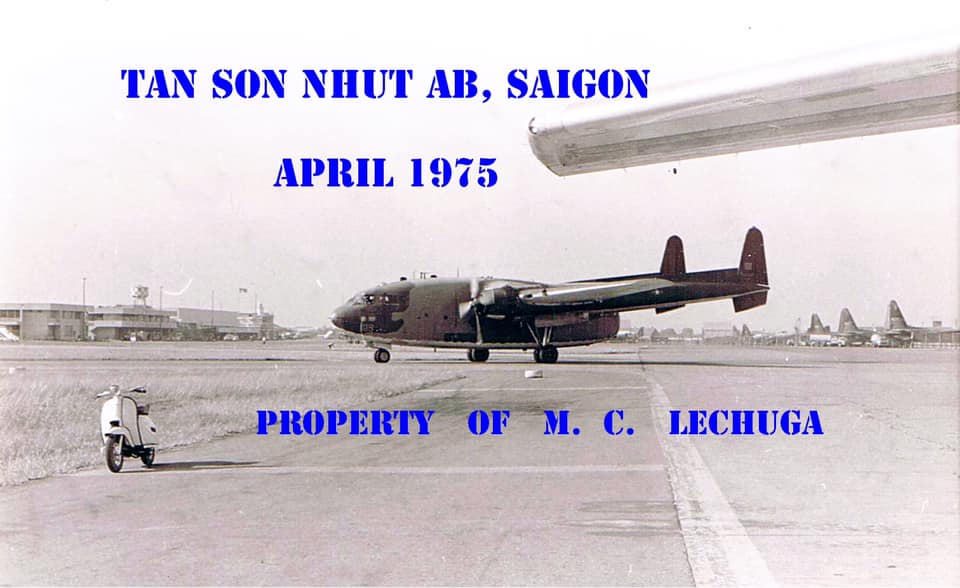

“VNAF C7 Caribous.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

“C47s of Vietnamese civilian airliners.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

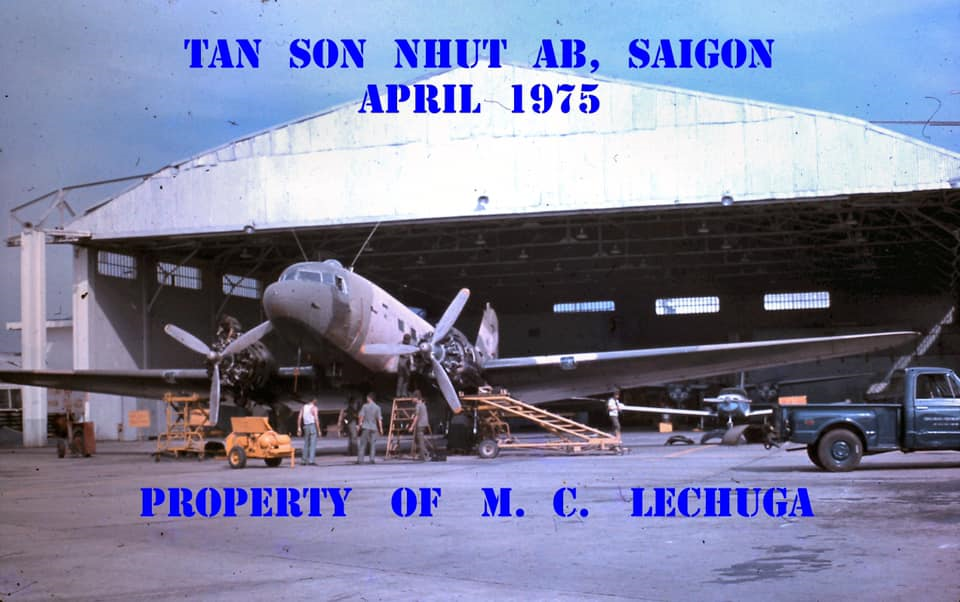

“South Vietnamese C47 undergoing maintenance. “ Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

“South Vietnamese guards beside the AC119s.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

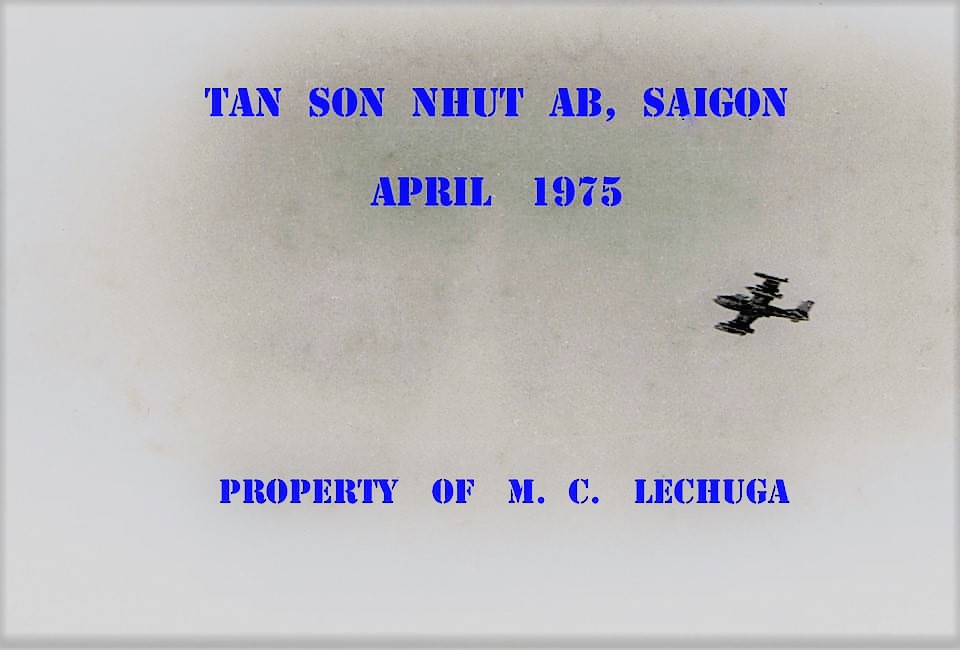

“AC119 STINGER gunship similiar to the one shot down on the morning of 29 April 1975 while engaging the North Vietnamese on the perimeter of Tan Son Nhut.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

“South Vietnamese A37 Dragonflys taxi for takeoff at Tan Son Nhut AB to bomb approaching North Vietnamese troops. These are similar to the ones captured at DaNang by the North Vietnamese and used to bomb Tan Son Nhut AB a few days later.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

10 April 1975 – Wednesday

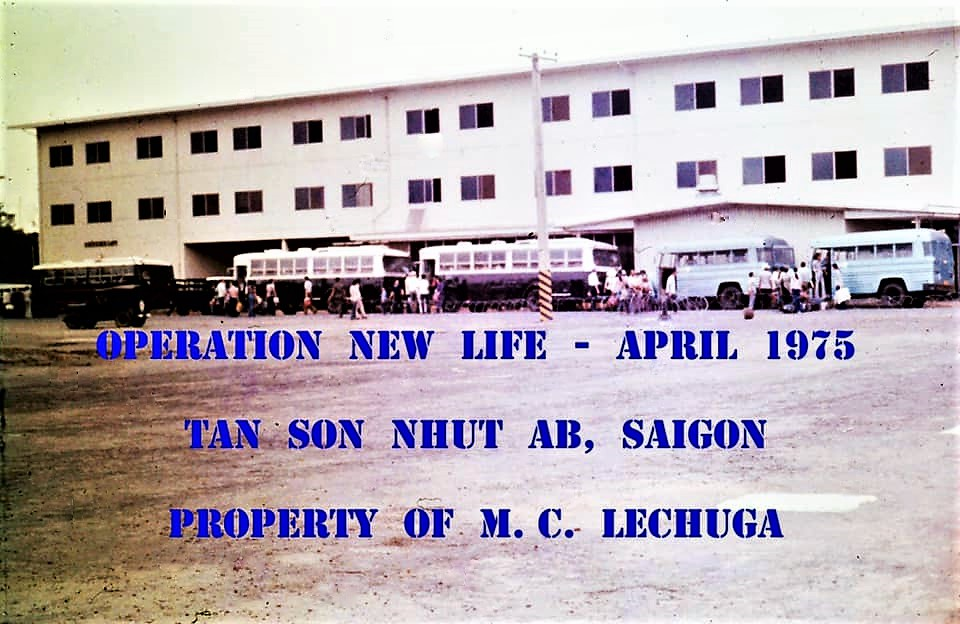

“USDAO compound (formerly Pentagon East -MACV Headquarters) where the passengers for our aircraft would be processed. The busses on the left would bring them out to the aircaft. “ Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

“These photos show the normal aircraft pax loading operation on the flight line. I took a photo of the base passenger terminal, but our pax were processed at the DAO Compound, former MACV Headquarters, then transported by bus to the aircraft.” Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

20 April 1975 – Sunday_________________

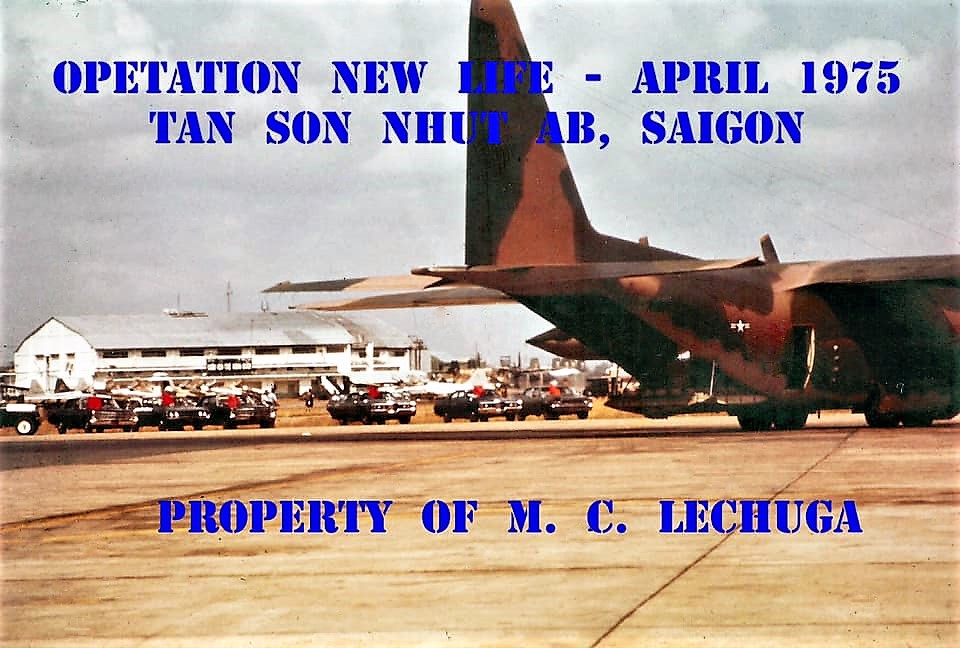

HISTORICAL NOTE: The flow of aircraft increased dramatically today as exit procedures were simplified and the floodgate of people wanting to leave increased. Prior to this date, only approximately 5000 passengers had been processed during April. The C141s were scheduled during the day and the C130s at night. The goal was to run 20 C141s and 20 C130s through Tan Son Nhut daily.

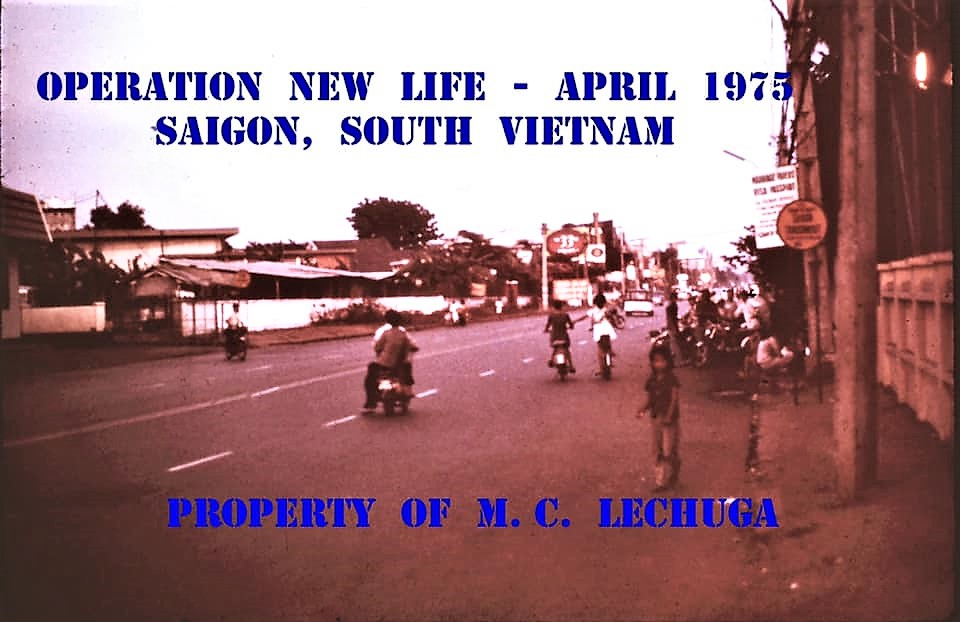

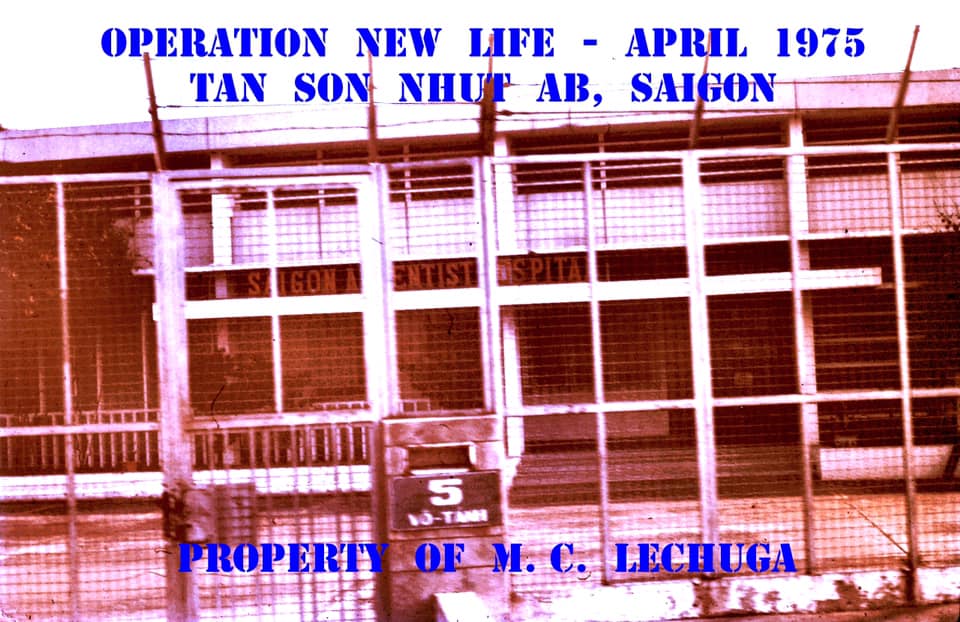

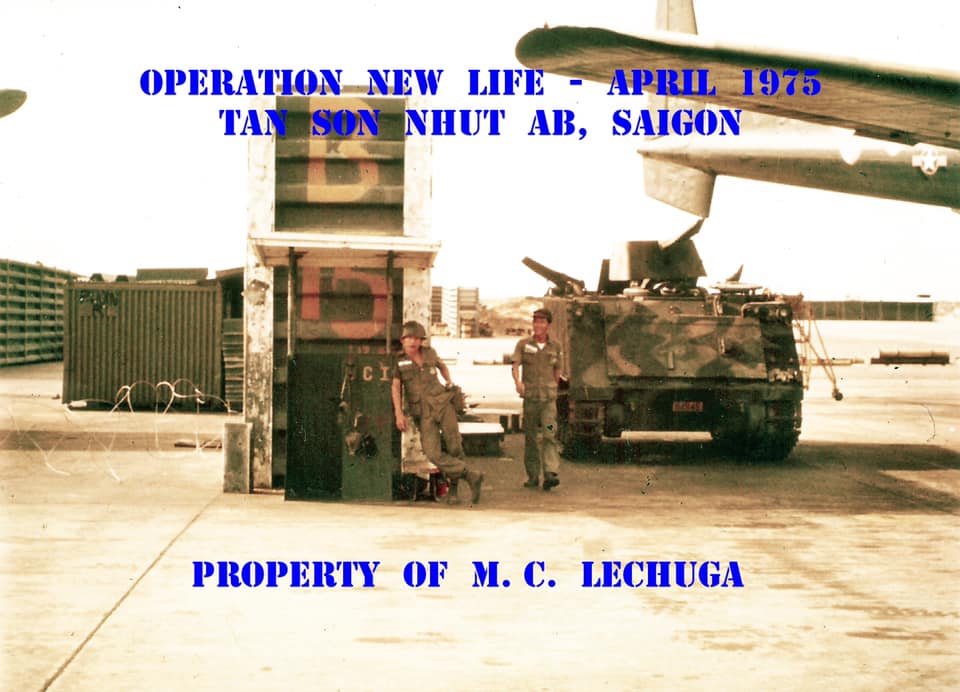

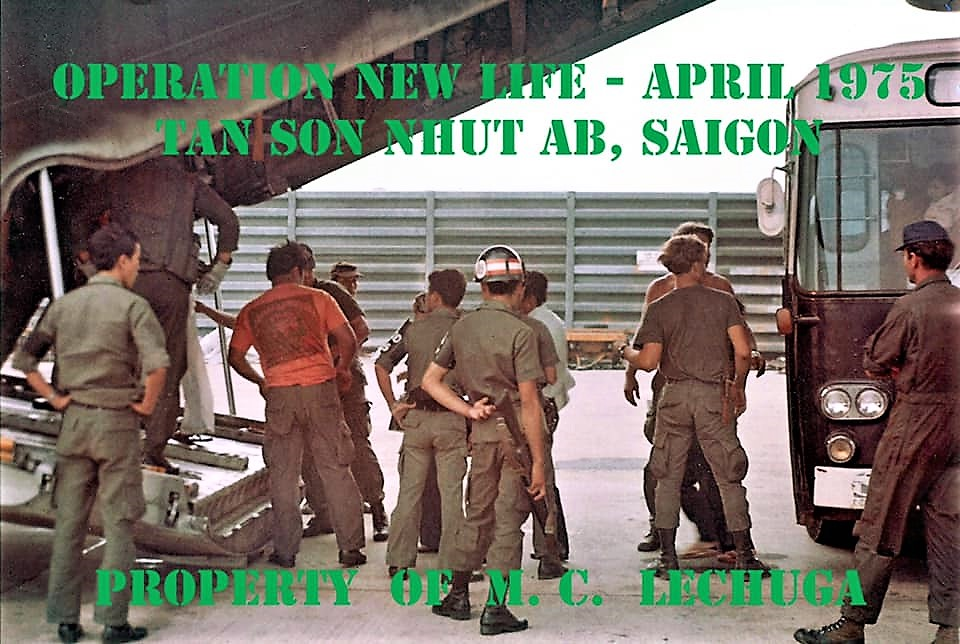

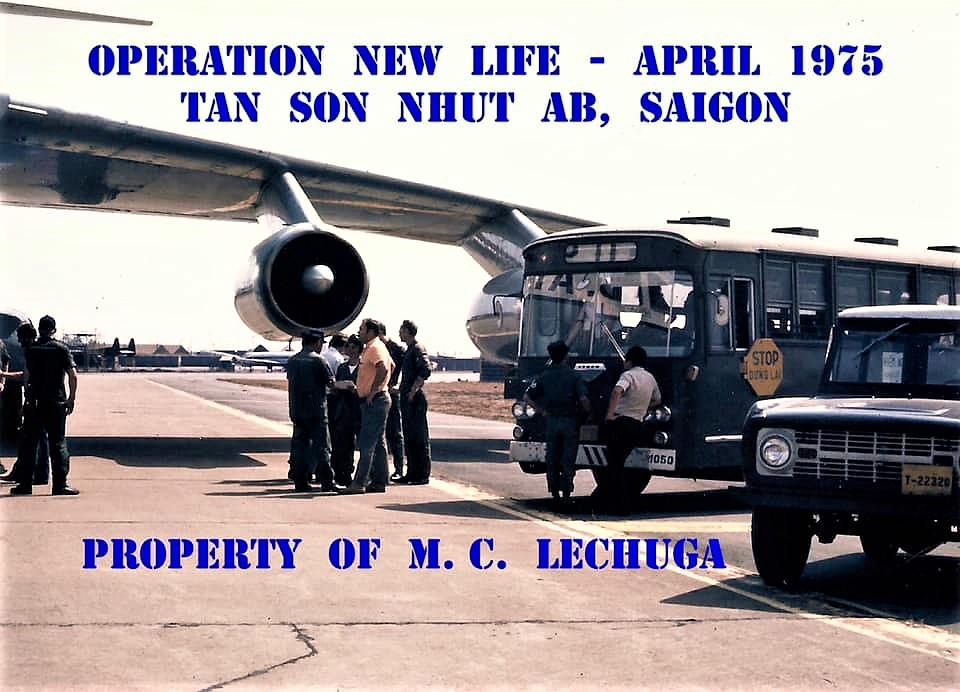

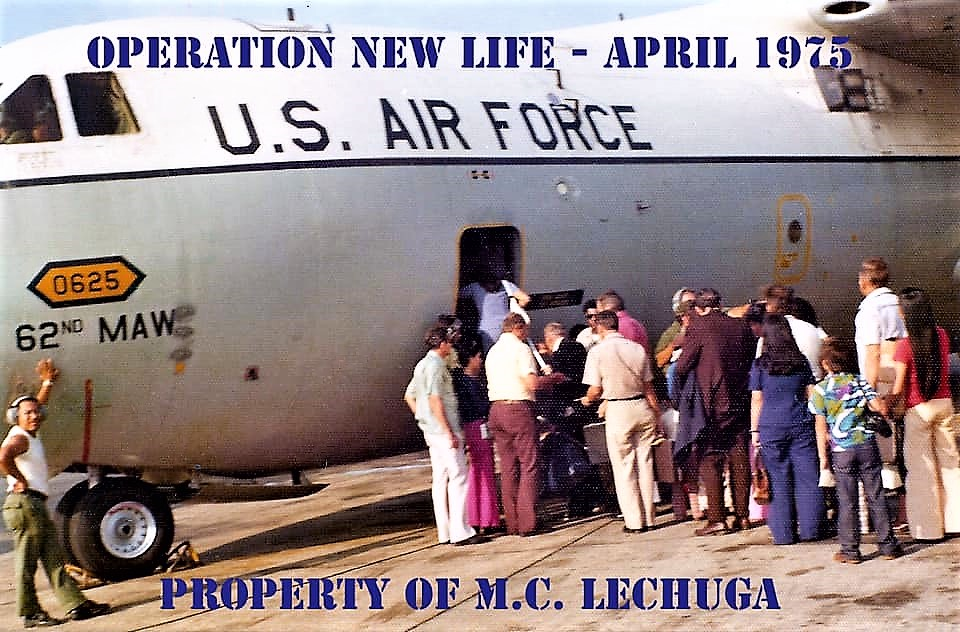

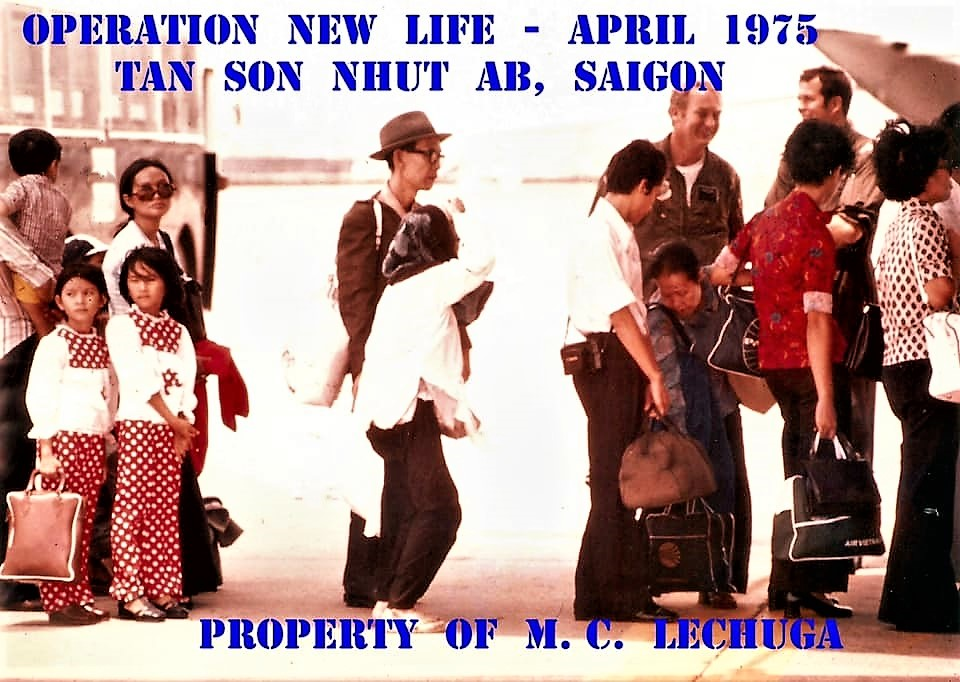

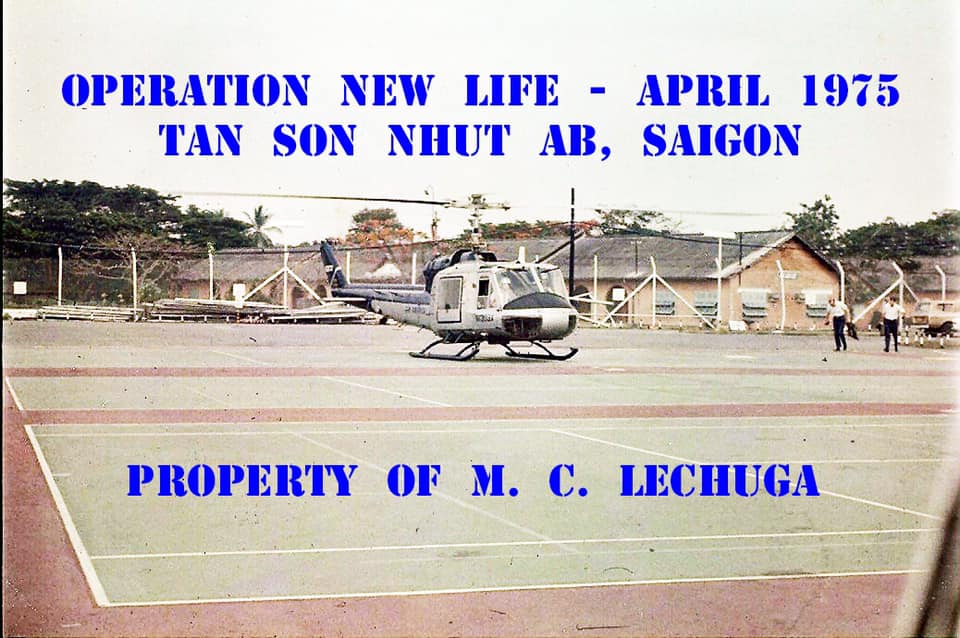

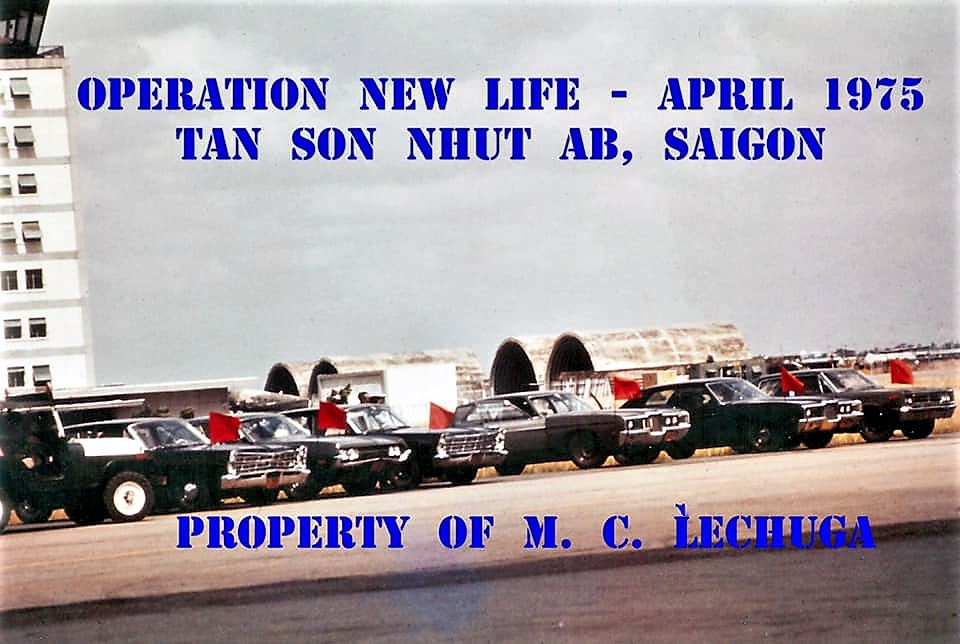

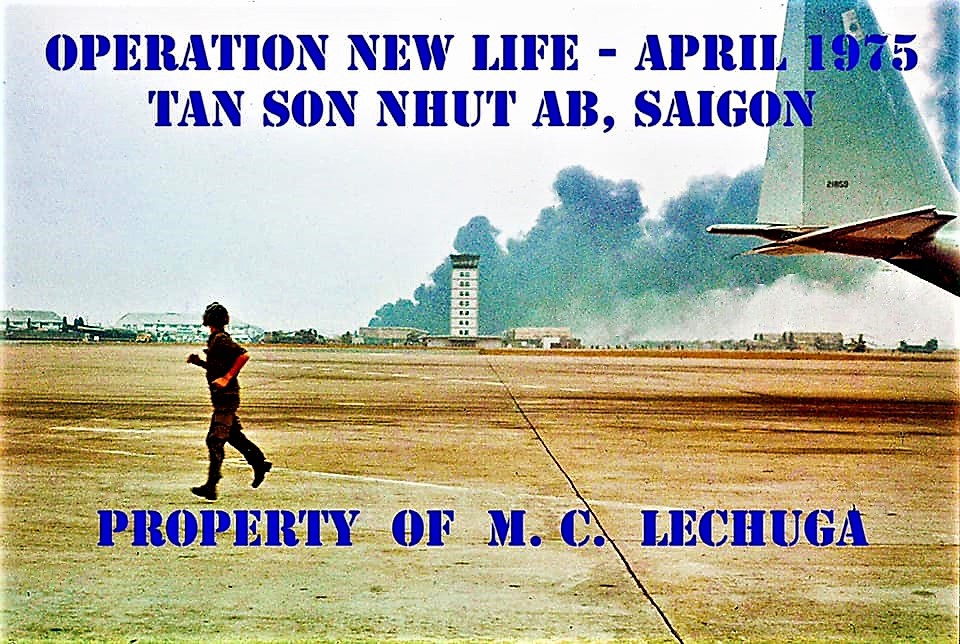

“We were now engaged in Operation New Life.”

“By the middle of April, the NVA divisions continued their relentless advance towards Saigon and a sense of urgency could be felt as the ops tempo of the evacuation effort ramped up. Our aircraft were evacuating Americans as well as South Vietnamese. “

The mysterious truck . . .

“Every now and then, once the pax were loaded, and the aircraft was ready for departure, a small truck with a windowless enclosure on its bed, would pull up in front of the aircraft and stop with its engine running. Then from the passenger side, a gentleman dressed in a light blue or light tan leisure suit, would get down and enter the aircraft. After a few minutes, one of three scenarios would happen.

First one, the leisure clad gentleman would exit the aircraft, return to the truck, and the vehicle would drive off.

Second scenario, the South Vietnamese military police, QC, would approach the aircraft and the truck would leave the area ASAP.

Third scenario, the truck would back up to the crew-entry ladder, the leisure suit would unlock the padlock on the doors of the enclosed space, then a flow of people would quickly enter the aircraft, and the truck would leave the area.”

HISTORICAL NOTE: 21 April 1975 The Battle of Xuân Lộc concluded with the ARVN retreating toward Saigon.

By 22 April 1975, 20 C-141 and 20 C-130s flights a day were flying evacuees out of Tan Son Nhut to Clark AB, some 1,000 miles away in the Philippines.

23 April 1975 – Wednesday_______________________

HISTORICAL NOTE: On 23 April President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines announced that no more than 2,500 Vietnamese evacuees would be allowed in the Philippines at any one time, further increasing the strain on MAC which now had to move evacuees out of Saigon and move some 5,000 evacuees from Clark Air Base on to Guam, Wake Island and Yokota AB in Japan.

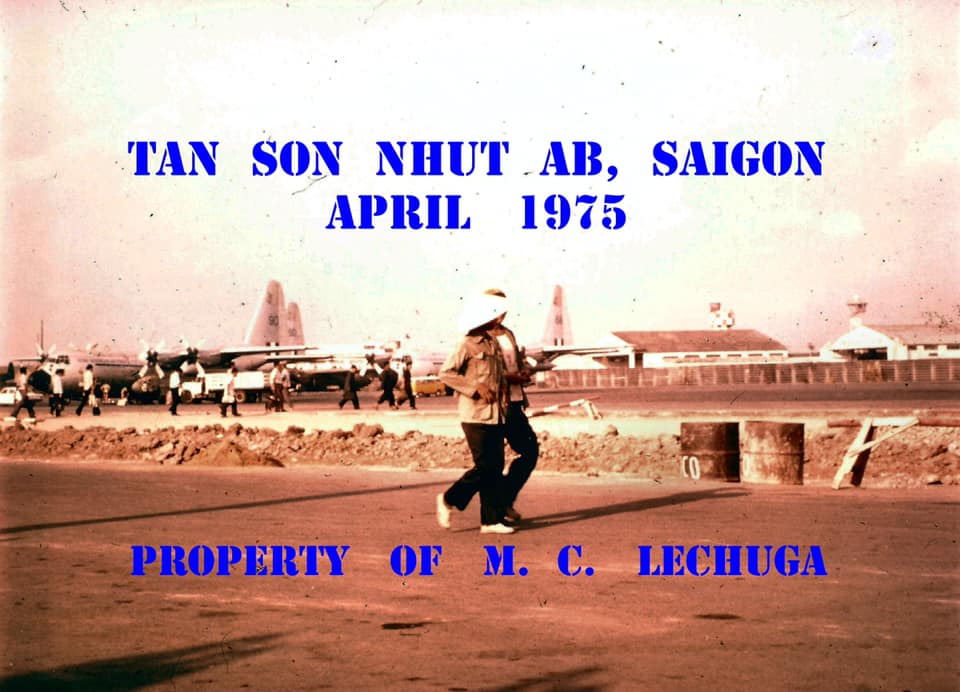

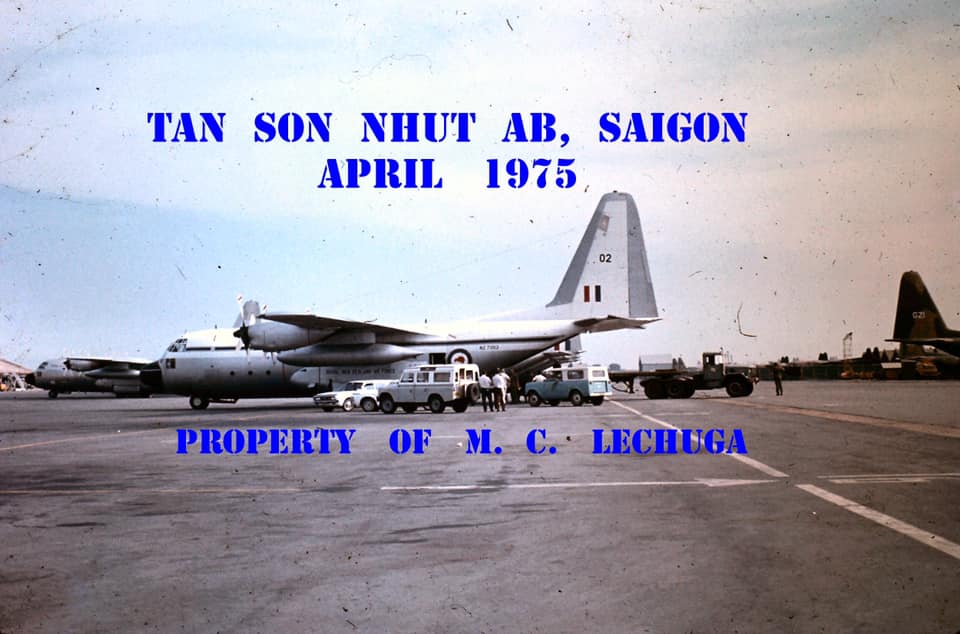

“In mid-April, operations at Tan Son Nhut AB, continued as though the NVA were not advancing towards Saigon. The photos I took, show work being done around the aircraft ramp and people going about their daily routine. Our aircraft were evacuating people every day, yet we were not the only ones who were taking people out. “

“These photographs were taken in between working evacuation flights. The NVA were getting closer to Saigon, yet operations at the base appeared normal. Guards were at their posts, perimeter defensive bunkers and anti-aircraft positions were manned, aircraft maintenance continued, ordnance was being delivered, and aircraft sorties flown. Soon this would change.

“A Pan Am Boeing 747 at Tan Son Nhut AB. The 747 had only entered service with Pan Am in January 1970. “ Mid April 1975. (Lechuga Photo)

“As the photos show, civilian airliners and military aircraft from various nations were also evacuating their personnel.”

HISTORICAL NOTE: On the night of 25 April 1975, a C118 propeller aircraft parked on the CIA ramp at Tan Son Nhut AB was met by US Ambassador Martin. Arriving also at the ramp via an unmarked car was former South Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu and family. Ambassador Martin said a few words to him and then President Thieu boarded the aircraft. It started engines and took off for Taiwan with no further fanfare. President Ford is said to have told him “Now is not a good time to come to the United Stateds.” Nguyen Van Thieu died in Boston, Mass on September 29, 2001 at the age of 78.

Also on this date, the Federal Aviation Authority out of the blue banned American commercial flights into South Vietnam. The US military questioned this decision and it was subsequently reversed; some operators had ignored it anyway. In any case this effectively marked the end of the commercial airlift from Tan Son Nhut.

C141 and C130 flights continued to fly into Tan Son Nhut AB as the NVA approached the city.

26 April 1975 – Saturday_________________________

“By now the NVA divisions were about to encircle Saigon and we could feel a tension in the activities at Tan Son Nhut. AA (Air America) was conducting business as usual.”

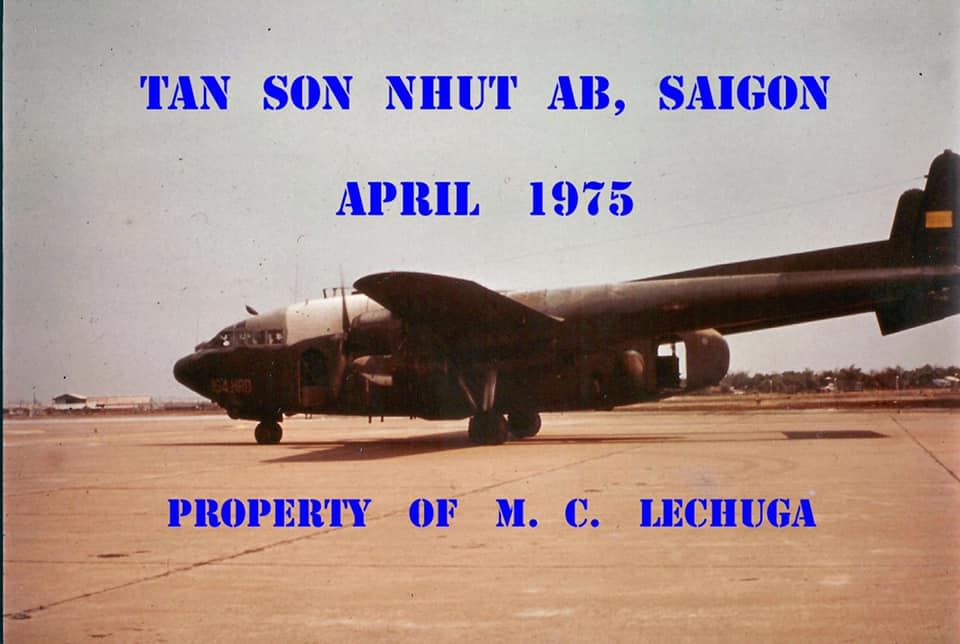

“SVNAF Herks were bringing troops in from the field.”

And one of our E-Flight C-130s, based at Clark, flew in a contingent of the NVA members of the Four Party Joint Military Commision.

HISTORICAL NOTE: Per the Paris Accords, a Four Party Joint Military Commission was formed to implement and monitor compliance with the provisions of the withdrawal, cease-fire, dismantling of bases, return of war prisoners, and exchange of information on those missing in action. The Commission was made up of the US, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong, and the North Vietnamese. USAF C130s flew regular missions between Hanoi and Saigon carrying these teams. These flights continued up to a few days before the final fall of South Vietnam.

26 April 1975 – Saturday_________________________

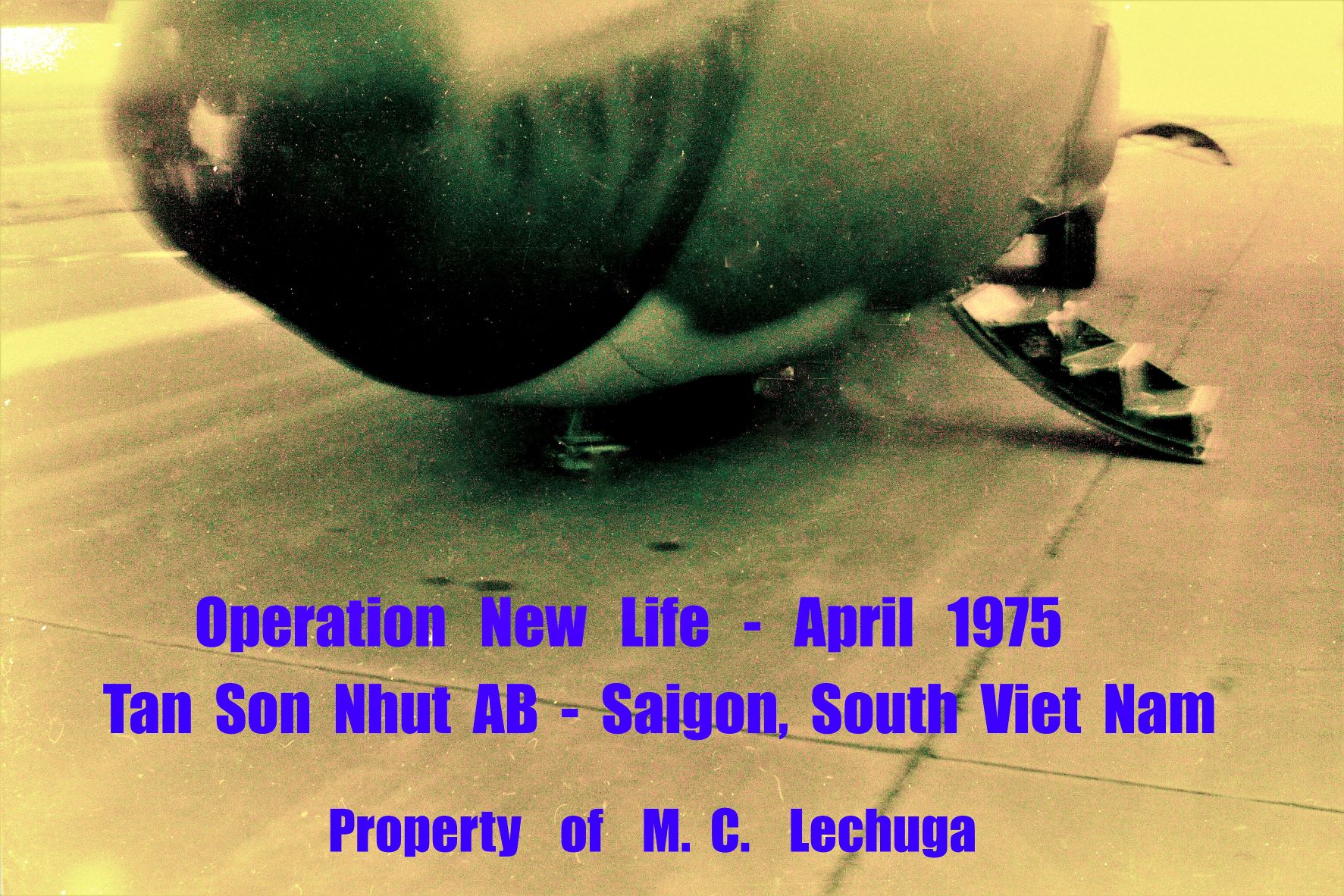

The C141 and C130 airlift continued throughout the day. One of the C130s suffered a broken nose gear strut on landing and closed the runway for a period of time. With little time to get it fixed, and no parts, the nose of the aircraft was jacked up, the nose gear extended and then chained down. It flew back to Clark with its gear down and made an unenventful landing at Clark AB. It was a long flight as they were unable to exceed 165 KIAs with the gear down.

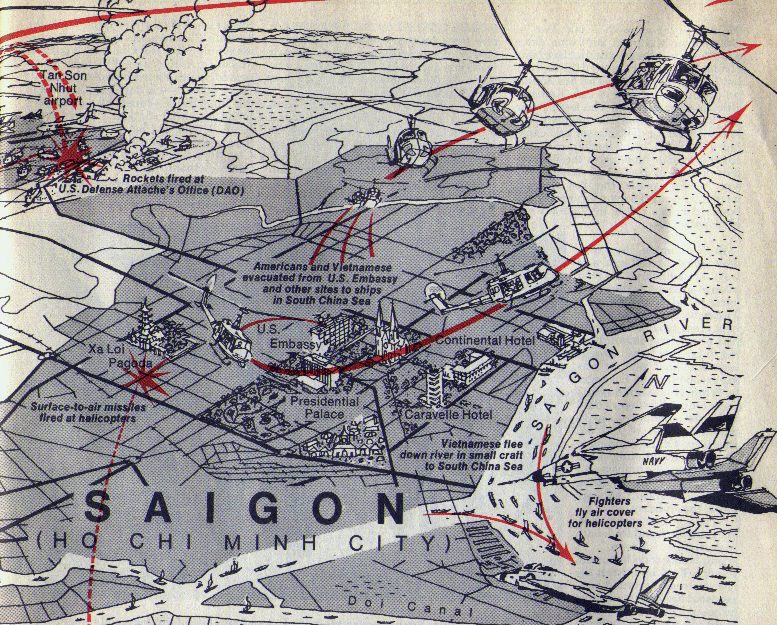

27 April 1975 – Sunday_________________________ By 27 April 1975, about 5 NVA Divisions encircled Saigon, and the end of South Vietnam was three days away.

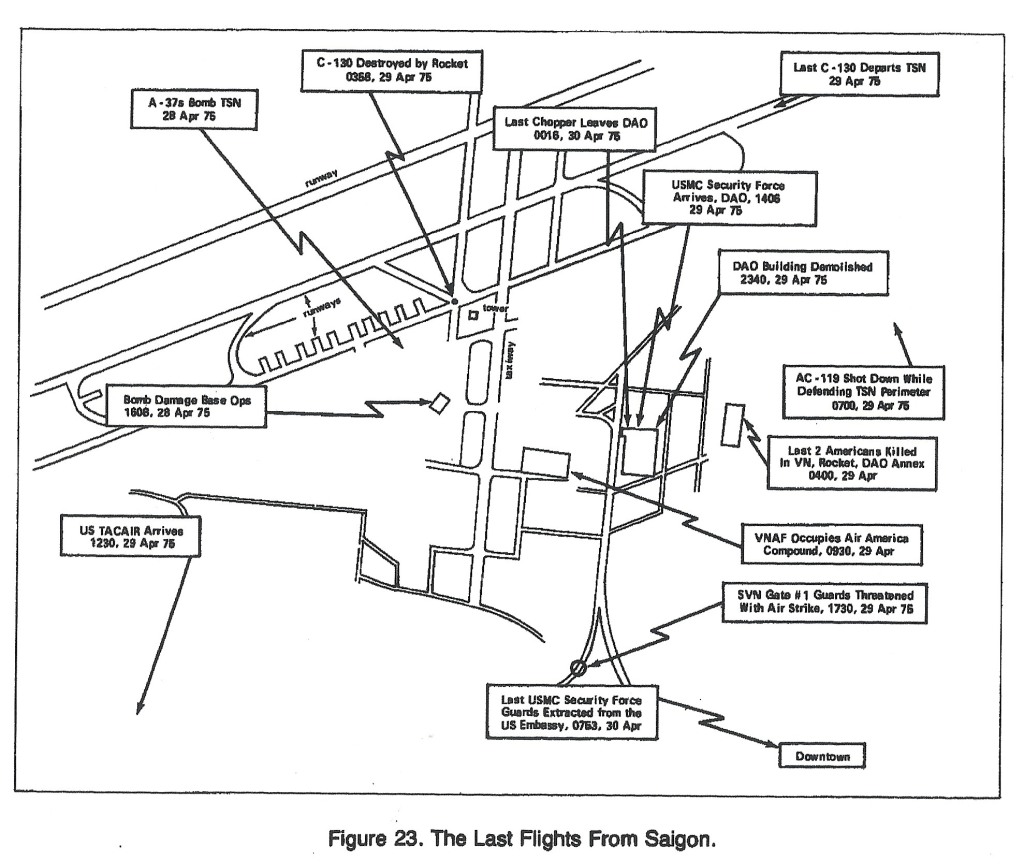

Map of the area around Saigon 25-29 April 1975 (Source: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/publications/publications-by-subject/End-of-the-Saga.html)

HISTORICAL NOTE: On 27 April PAVN rockets hit Saigon and Cholon for the first time since the 1973 ceasefire. It was decided that from this time only C-130s would be used for the evacuation. No more C-141s into Saigon.

“We had no clue that on the 28th, TSN, would be bombed.”

28 April 1975 – Monday__________________________

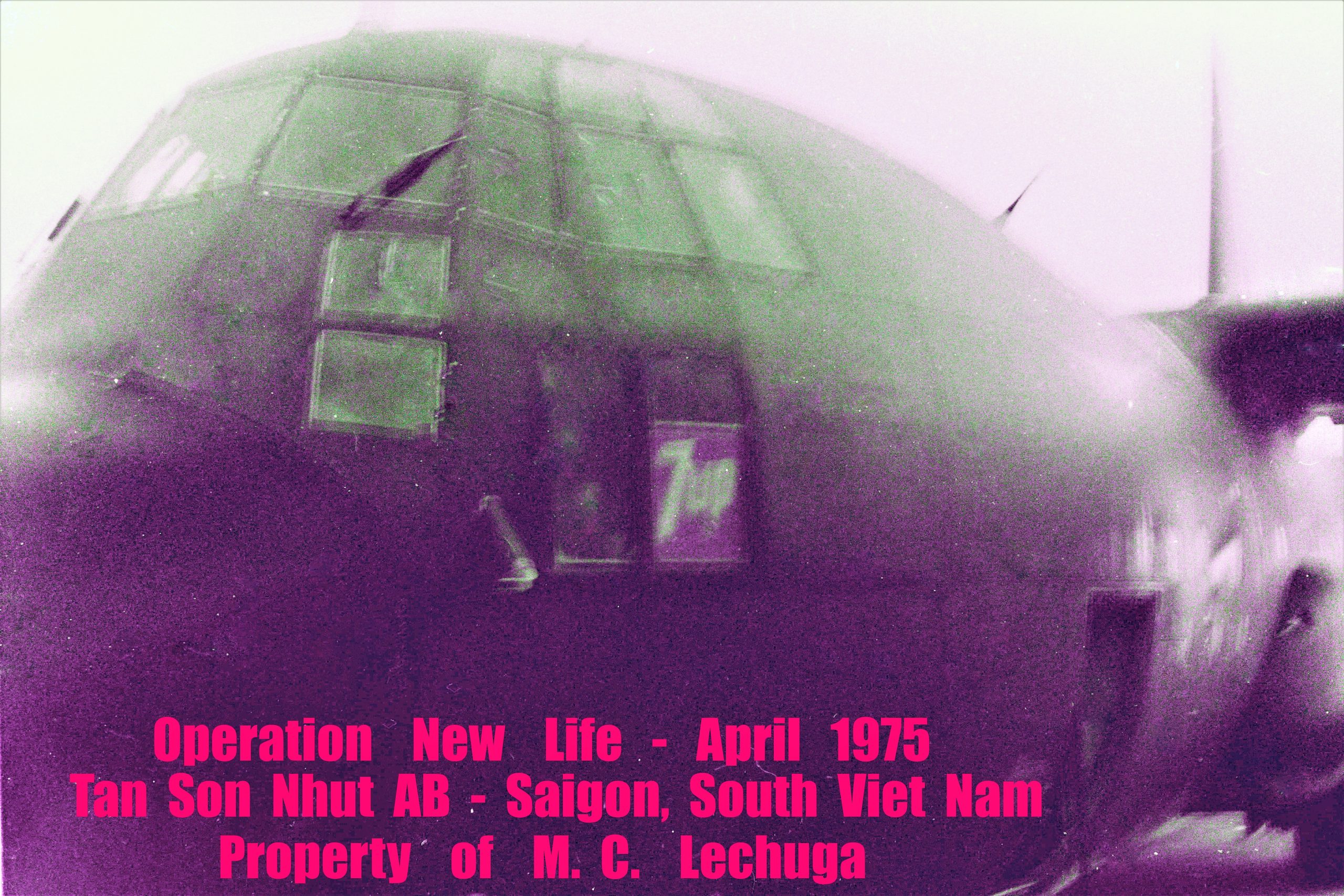

The C130 airlift continued between Clark AB and Tan Son Nhut AB throughtout the night and day now since there were no more C141s flying into Saigon.

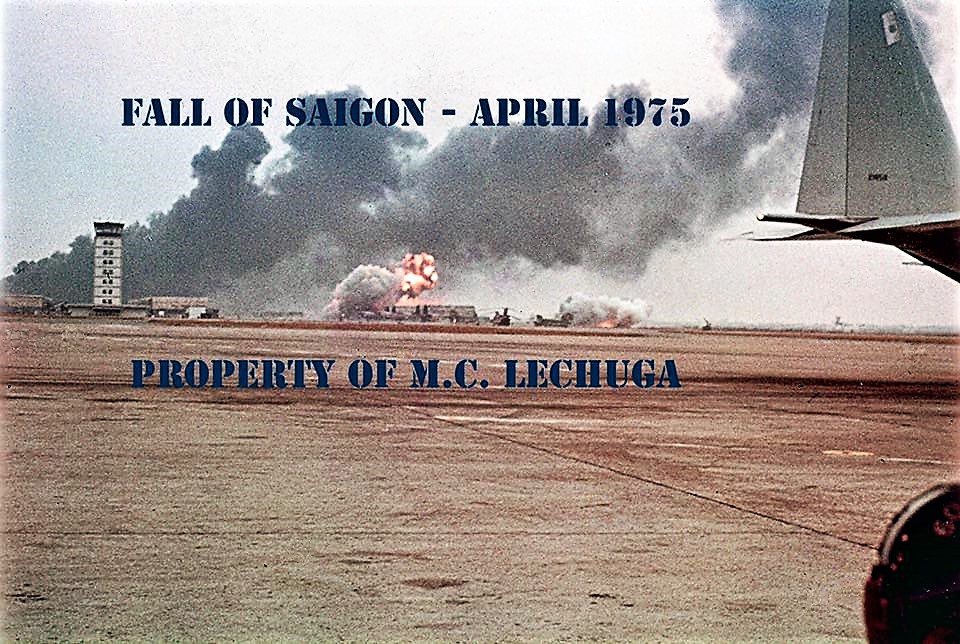

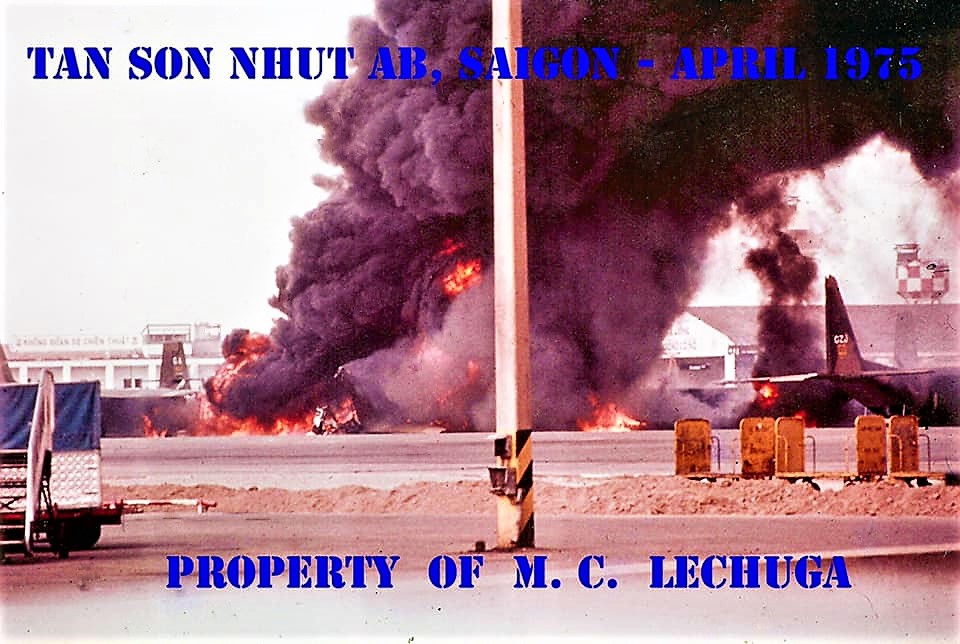

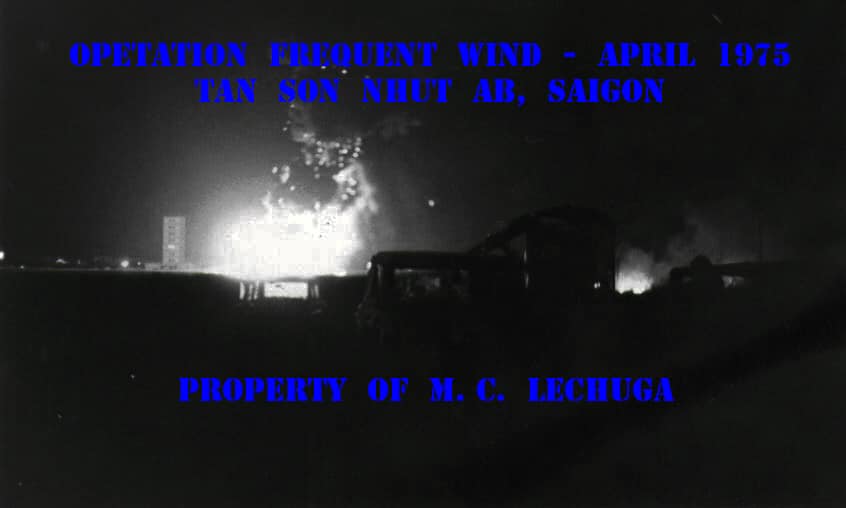

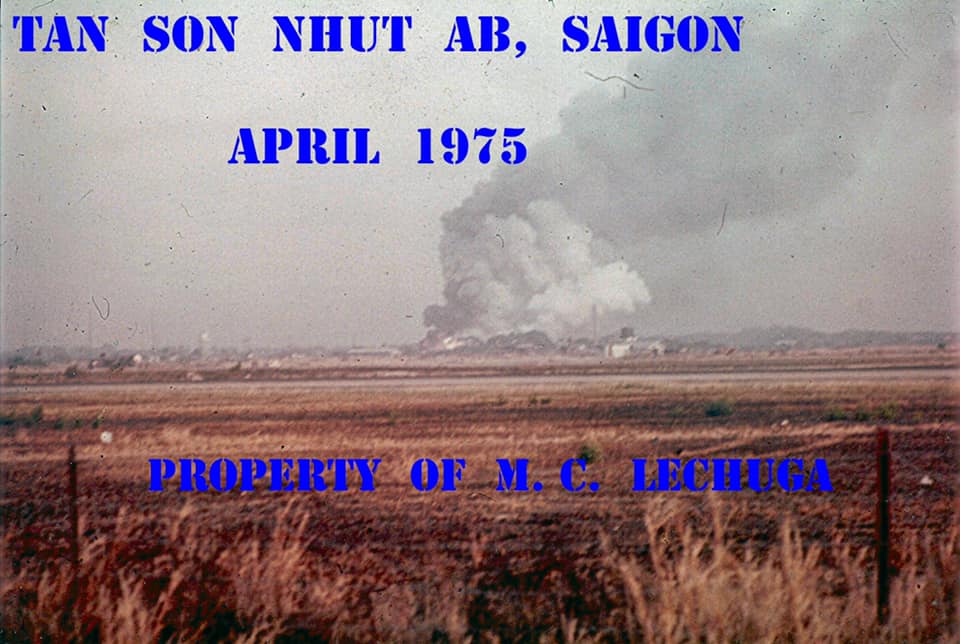

HISTORICAL NOTE: On 28 April at 18:06, five A-37 Dragonflies captured at Danang AB attacked Tan Son Nhut AB. Piloted by former defector VNAF and NVA pilots,they dropped six Mark 81 250 lb bombs on the base, damaging aircraft. VNAF F-5s took off in pursuit, but they were unable to intercept the A-37s. USAF C-130s leaving Tan Son Nhut reported receiving PAVN .51 cal and 37 mm anti-aircraft (AAA) fire and harassment from the A37s. Sporadic PAVN rocket and artillery attacks also started to hit the airport and air base. The attack shut down the flow of C130. There would be no more USAF C130s into Tan Son Nhut until 0300 the next morning.

Historical Note: A loaded C-130, flown by Capt Ken Rice, 345 TAS, took off just prior to the attack and reported heavy ground fire on climb out and had to duck into a thunderstorm to avoid friendly fire. A second C-130 pilot, 1st Lt Fritz Pingle, from Clark AB, took off shortly before Rice and had one of the A37s join up on his left side for awhile. They went down to 500feet AGL and 280 KIAS but the A37 stayed with them until the coast where they broke off. They were unsure if they were fired upon. Pringle was able to contact Clark AB via Clark Airways HF radio to get the flow of aircraft into Tan Son Nhut turned off. (Planes were scheduled every 20 minutes) The last C130 on the ground was able to take off and proceed back to Clark. (Last Flight From Saigon)

“After the bombing of Tan Son Nhut AB, by A-37s at Danang, led by a SVNAF pilot defector, our aircraft maintenance team waited further orders. The two C130s had taken off and no more were inbound. We kept an eye on the base perimeter nearest our location in case of a ground assault by the NVA.”

“We returned to our “home” to await further orders and we wondered if we were about to be attacked by the NVA ground forces.”

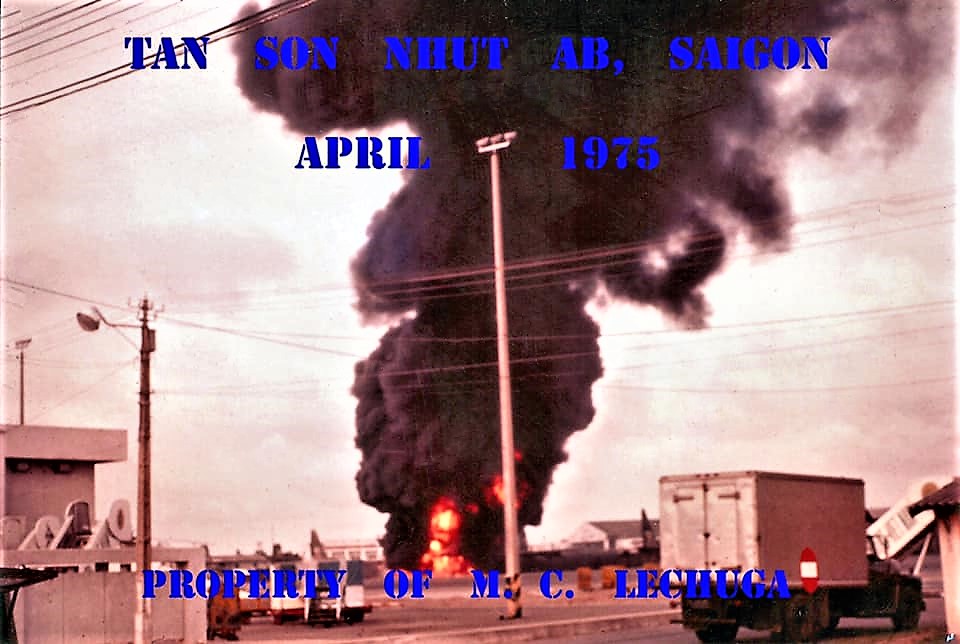

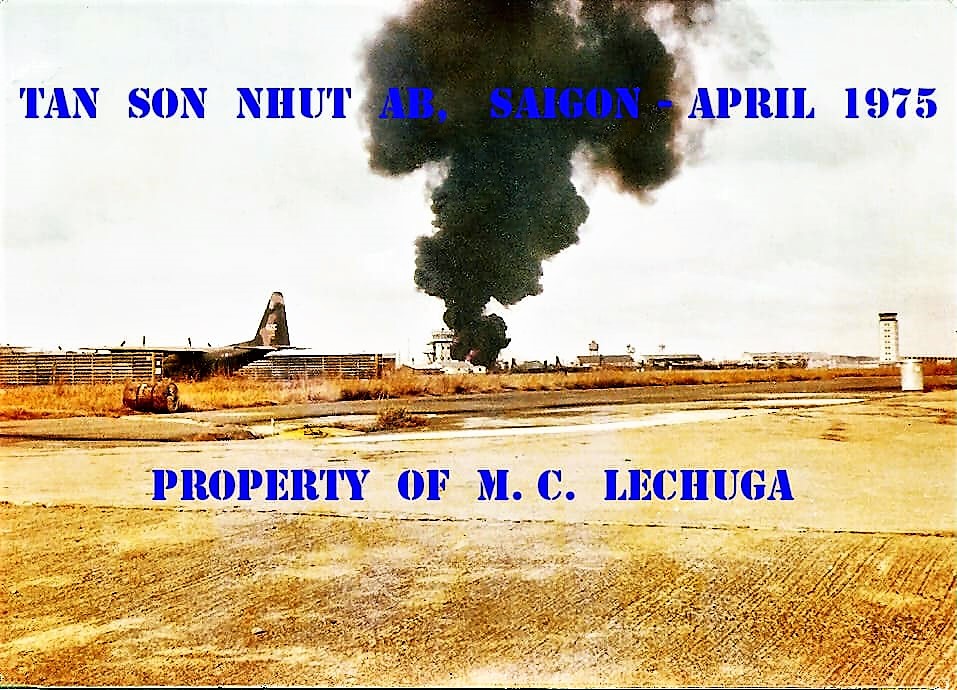

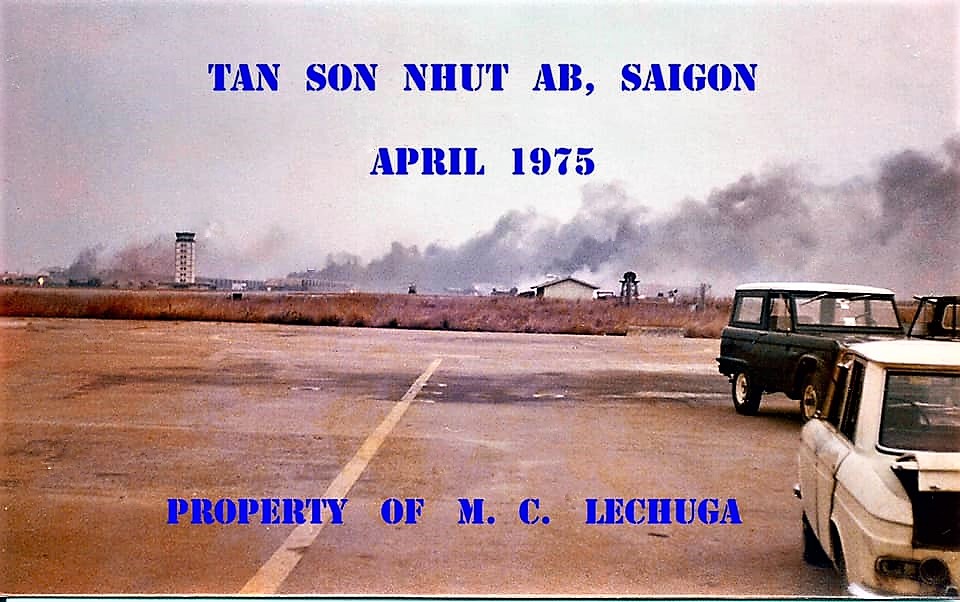

“SVN personnel are shooting M-16s into the air, anti-aircraft guns are firing, and SVNAF aircraft are burning.”

“About an hour after the action we were equipped with helmets and flak vests. We were ready to party.”

Historical Note: Though the airlift had stopped temporarily after the attack, two C-130s continued holding east of Tan Son Nhut. At 2000 they were cleared in, picked up their passenger loads (300 total), and departed without incident. At the same time, Clark commanders decided to resume the flow of C-130s. At 2100 Maj Gen Smith relayed the word through the Evacuation Control Center that sixty C-130 sorties were scheduled for Tuesday – 29 April to evacuate a planned 10,000 people. The first would arrive at 0300. ( Last Flight From Saigon. USAF Southeast Asia Monograph Series. Volume IV, Monograph 6 Air Force Historical Studies Office,AF/HO,1190 Air Force Pentagon,Washington,DC,20330-1190 )

29 April 1975 – Tuesday_________________________

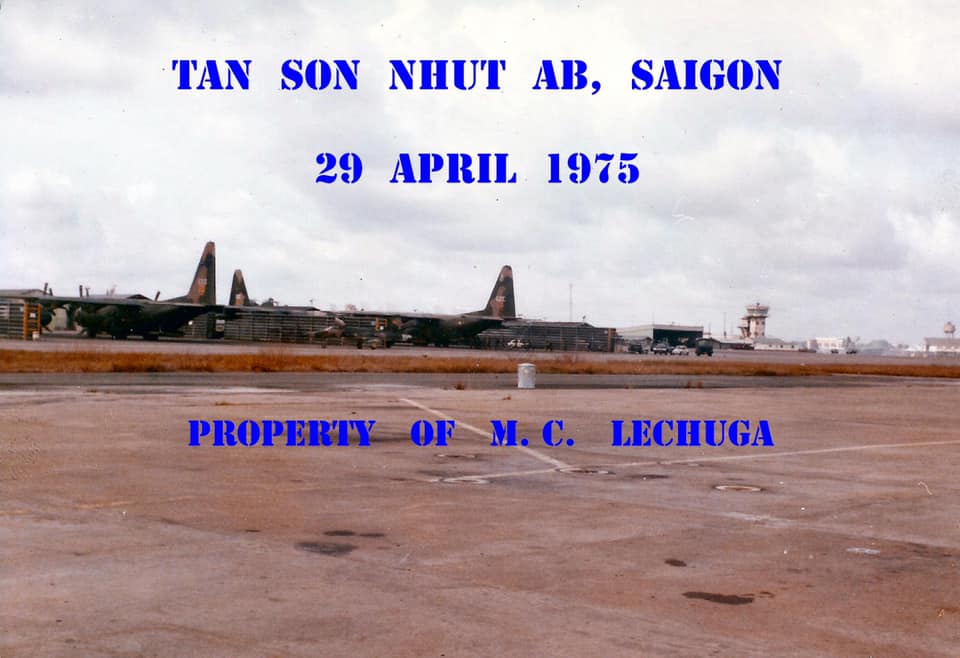

Three USAF C130s from Clark AB land in the morning darkness of Tuesday, 29 April 1975. . . .

forces posed a serious threat with weapons consisting of SA-7 surface-to-air, hand-held missiles and a variety of conventional Antiaircraft Artillery including 23mm, 37mm, and radar-directed 57mm

and 85mm guns. Reports revealed that at least one SA-2 missile battery was set up in the newly captured Bien Hoa area, 18 miles away.

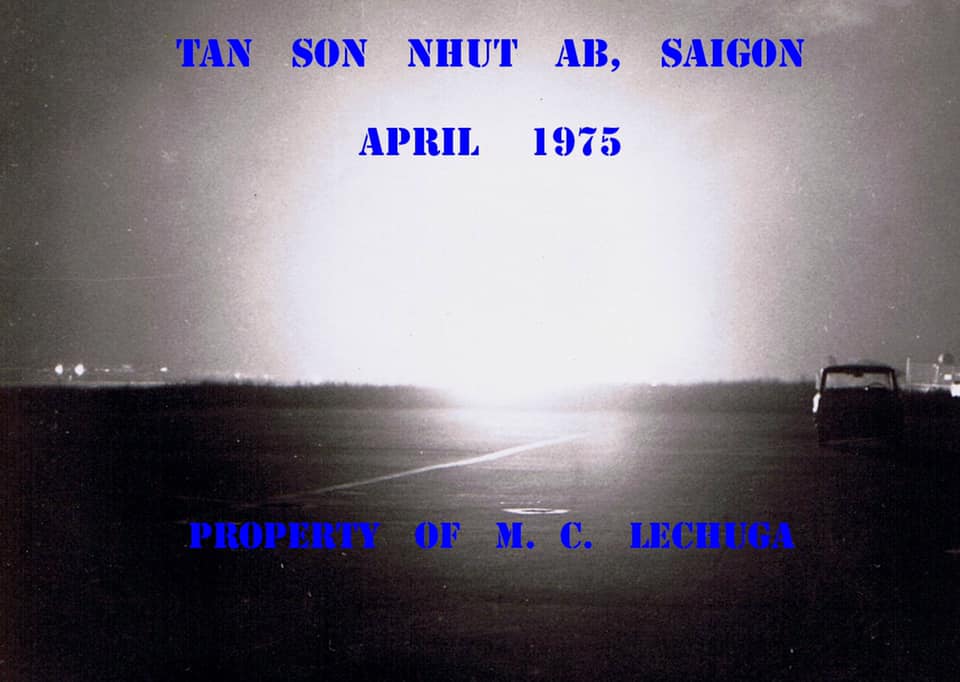

“Both planes left and our small group of maintenance and aerial port guys returned to our flight line quarters on the northeast side of the base to watch the “fireworks”. The NVA rockets continued to come in and hit the base sporadically throught out the rest of the night.”

HISTORICAL NOTE: The rockets and what sounded like heavy artillery continued throughout the day with the greatest concentration of 40 rounds per hour between 0430 and 0800. Following the initial barrage, which seemed to hit indiscriminately in and around the Tan Son Nhut area, the

rocket fire became more and more concentrated on the flight line and fuel and ammo storage areas. In fact, after about 0430, no one remembered any more rockets hitting in the Defense Attache Office Compound or Annex ( from Last Flight From Saigon. USAF Southeast Asia Monograph Series. Volume IV, Monograph 6 Air Force Historical Studies Office,AF/HO,1190 Air Force Pentagon, Washington, DC, 20330-1190 )

“We went back to our quarters area and watched the Herk burn until daybreak. We got hit with additional rocket salvos until morning and although it appeared we were not targeted, some rockets fell close to our location. We could also see combat going on at the base perimeter closest to our position, less than a mile away. We could see streams of red tracers going out, and streams of green tracers coming in. We guessed the NVA was probing the base perimeter defenses and we hoped they were not ready for a full scale assault. Luckily, they were not.”

Coincidentally with the hit on the USAF C130, another NVA rocket made a direct hit on an USDAO compound checkpoint not far away at approximately 0400. Killed instantly were two USMC guards who had only been in country 7 days. (Left) Cpl. Charles McMahon, 21, an athletic daredevil from Massachusetts, and (Right) Lance Cpl. Darwin L. Judge, 19, a blue-eyed Eagle Scout from Iowa, and became the last Americans killed in action in the Vietnam War. Maj Dellegatti of the SOA, who was enroute back to Tiger Ops, had spoken briefly to the Marine guards only five seconds before the impact killed them. Their bodies would not be returned to the United States until February 1976.

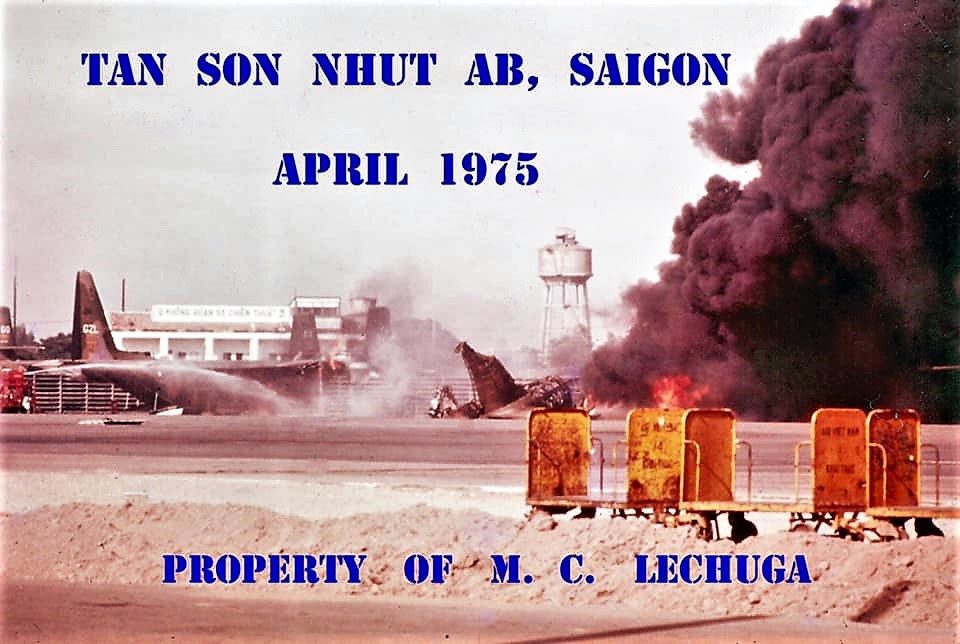

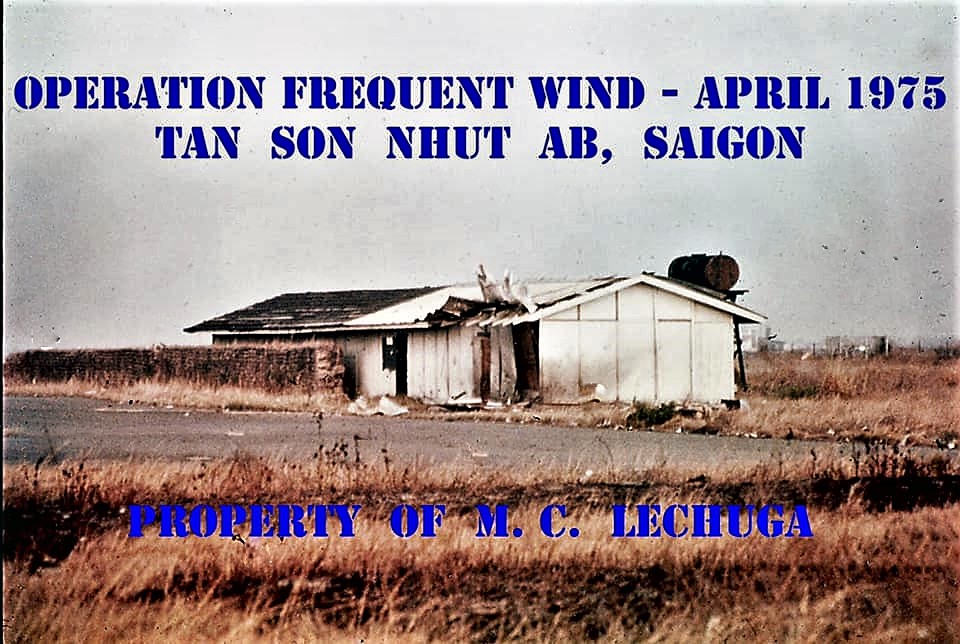

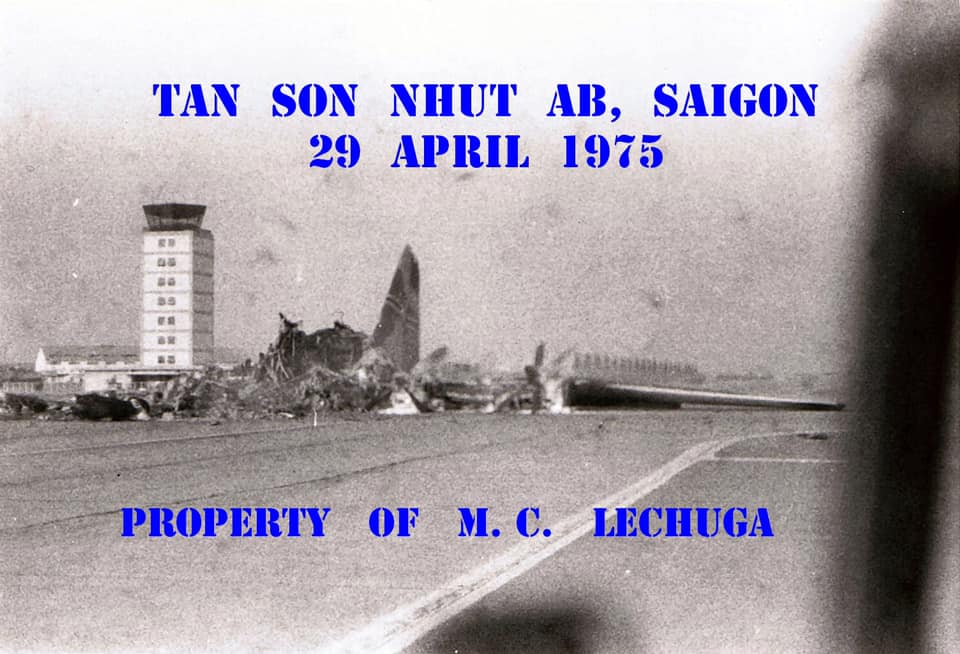

The sun comes up and reveals the damage . . . . . . . .

With the NVA on the perimeter, the South Vietnamese Air Force launch attacks against them . . .

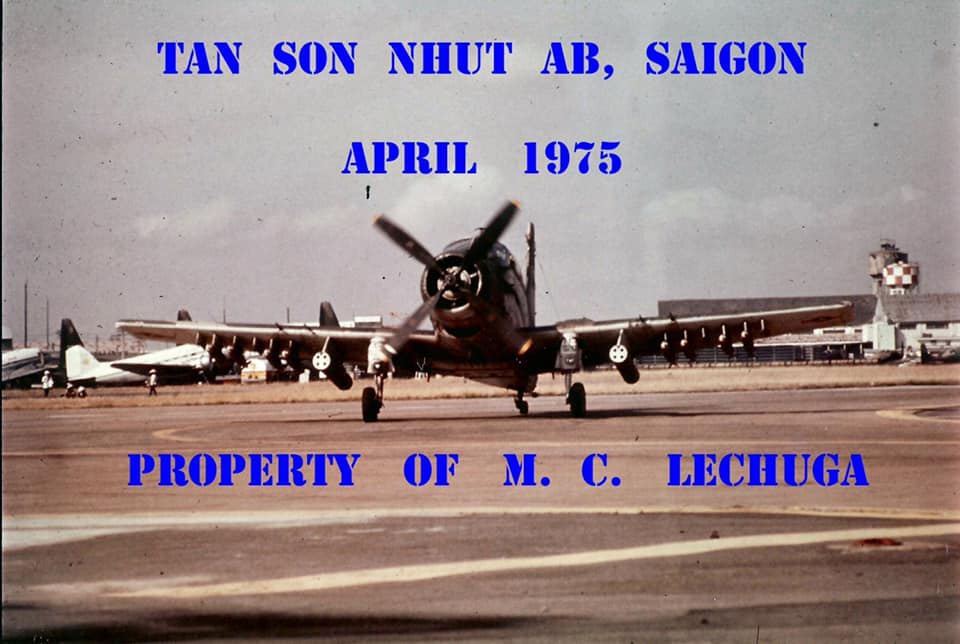

“In the early morning of 29 April, two VNAF A-1Es and one AC-119 gunship took off on a bombing and strafing mission against the NVA force attacking the base perimeter near our location. One A-1E would drop bombs on the enemy, the AC-119 would execute a strafing pass, then the second A-1E would make a bomb run.”

“A VNAF AC119 gunship taxis out to provid fire support on the perimeter of Tan Son Nhut AB on the morning of 29 April 1975. This aircraft would be shot down within a few hours by a NVA SA7 Strella surface to air missile.” (Lechuga Photo)

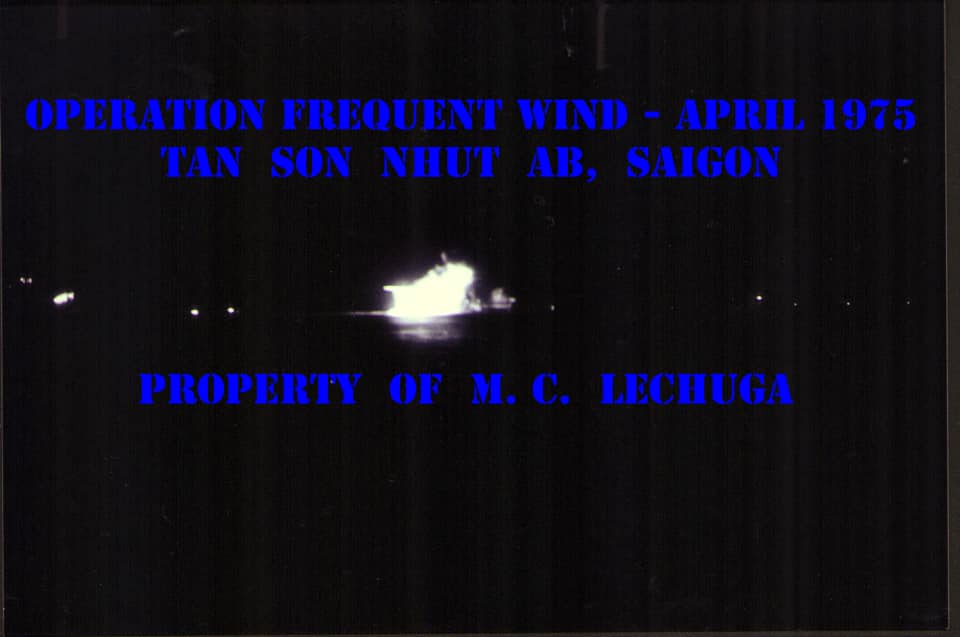

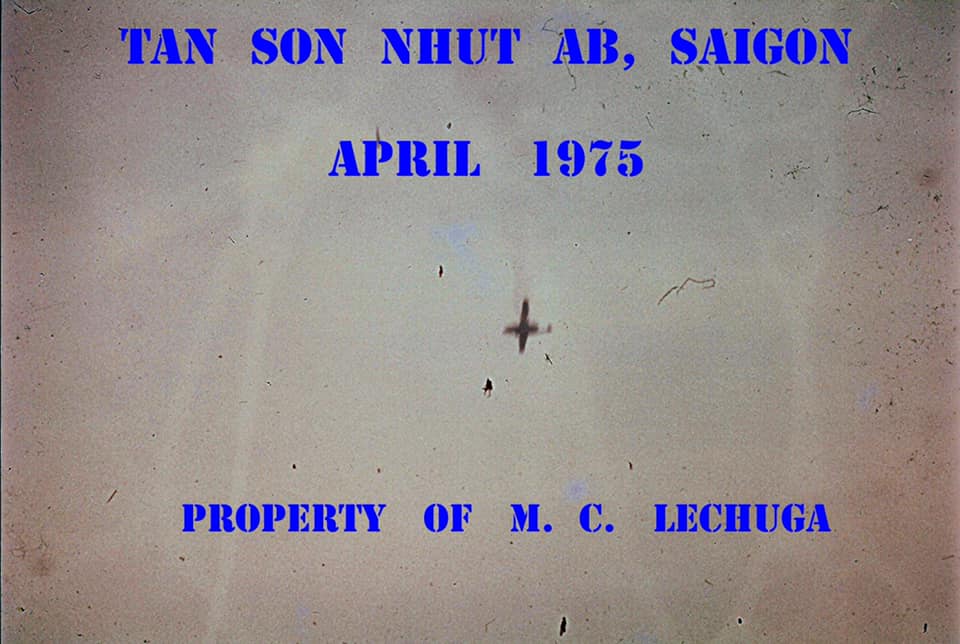

The VNAF AC-119 is shot down by an SA-7

The AC119 hits the ground and explodes. What appears to be an open parachute can be seen just above and to the left of the explosion. It was later reported one gunner was able to escape the doomed aircraft. The rest of the crew perished. It was a horrible feeling as we helplessly watched the sad event.

“The aircraft was spinning, and we saw one of its twin tail booms separate from the rest of the aircraft. Just before the gunship crashed and exploded I saw what seemed to be a parachute canopy open up at a very low altitude. But others in our group said it was impossible to bail out of a spinning aircraft due to the excessive g-forces. Dinh Nguyen, an NDI troop, serving with the SVNAF at TSN, researched a Vietnamese article reporting the miraculous survival of the one gunship crew member.”

HISTORICAL NOTE: At dawn on 29 April the RVNAF began to haphazardly depart Tan Son Nhut Air Base as A-37s, F-5s, C7s, C-119s and C-130s departed for Thailand while UH-1s took off in search of the ships of Task Force 76. Some RVNAF aircraft stayed to continue to fight the advancing PAVN. One AC-119 gunship had spent the night of 28/29 April dropping flares and firing on the approaching PAVN. At dawn on 29 April two A-1 Skyraiders began patrolling the perimeter of Tan Son Nhut at 2,500 feet (760 m) until one was shot down, presumably by an SA-7 missile. At 07:00 the AC-119 was firing on PAVN to the east of Tan Son Nhut when it too was hit by an SA-7 and fell in flames to the ground.

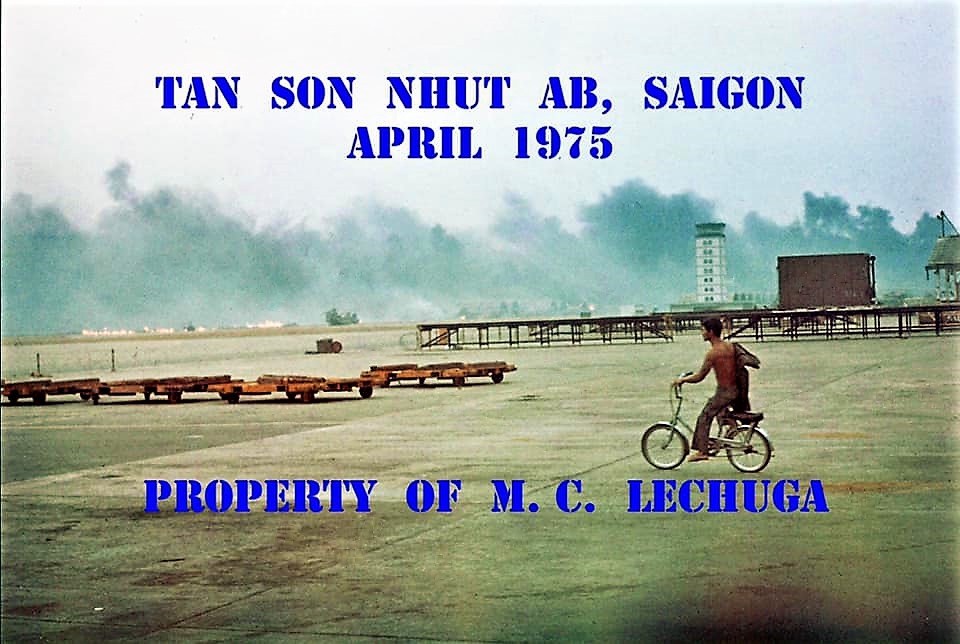

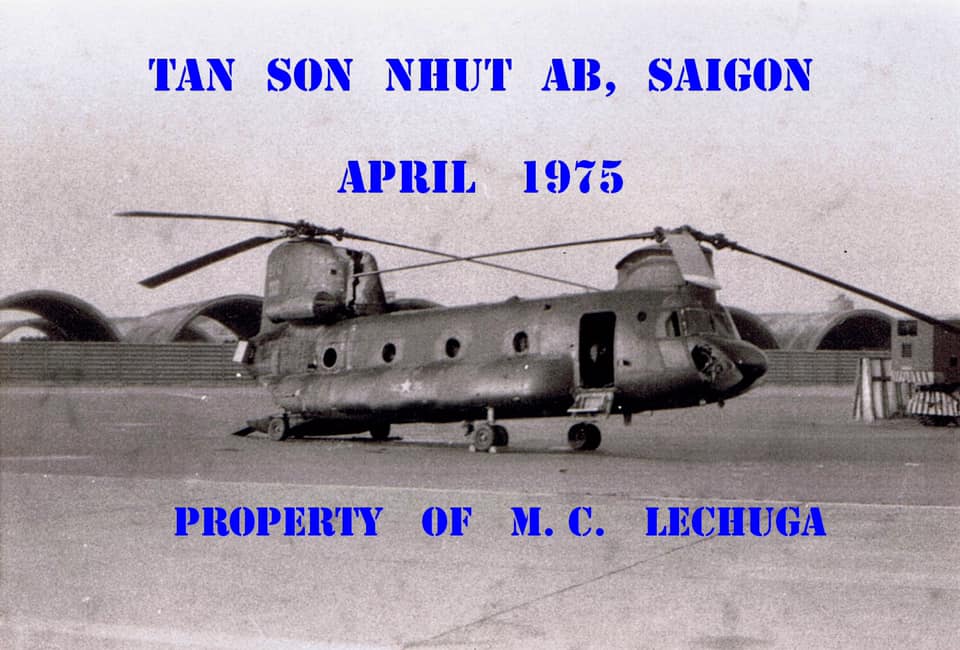

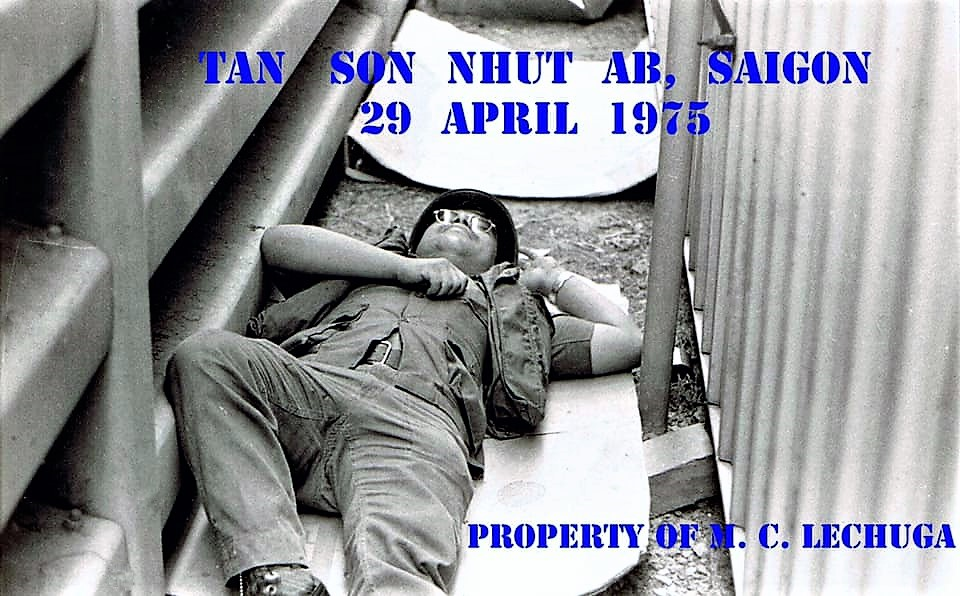

At 08:00 on 29 April Lieutenant General Trần Văn Minh, commander of the RVNAF and 30 of his staff arrived at the DAO Compound demanding evacuation, signifying the complete loss of RVNAF command and control. At 10:51 on 29 April, the order was given by CINCPAC to commence Operation Frequent Wind, the helicopter evacuation of US personnel and at-risk Vietnamese.

In the final evacuation, over a hundred RVNAF aircraft arrived in Thailand, including twenty-six F-5s, eight A-37s, eleven A-1s, six C-130s, thirteen C-47s, five C-7s, and three AC-119s. Additionally close to 100 RVNAF helicopters landed on U.S. ships off the coast, although at least half were jettisoned. One O-1 managed to land on the USS Midway, carrying a South Vietnamese major, his wife, and five children.

The ARVN 3rd Task Force, 81st Ranger Group commanded by Maj. Pham Chau Tai defended Tan Son Nhut and they were joined by the remnants of the Loi Ho unit. At 07:15 on 30 April the PAVN 24th Regiment approached the Bay Hien intersection, about a mile from the base’s main gate. The lead T-54 was hit by M67 recoilless rifle and then the next T-54 was hit by a shell from an M48 tank. The PAVN infantry moved forward and engaged the ARVN in house to house fighting forcing them to withdraw to the base by 08:45. The PAVN then sent 3 tanks and an infantry battalion to assault the main gate and they were met by intensive anti-tank and machine gun fire knocking out the 3 tanks and killing at least 20 PAVN soldiers. The PAVN tried to bring forward an 85mm antiaircraft gun but the ARVN knocked it out before it could start firing. The PAVN 10th Division ordered 8 more tanks and another infantry battalion to join the attack, but as they approached the Bay Hien intersection they were hit by an airstrike from RVNAF jets operating from Binh Thuy Air Base which destroyed 2 T-54s. The 6 surviving tanks arrived at the main gate at 10:00 and began their attack, with 2 being knocked out by antitank fire in front of the gate and another destroyed as it attempted a flanking manoeuvre. (Wikipedia)

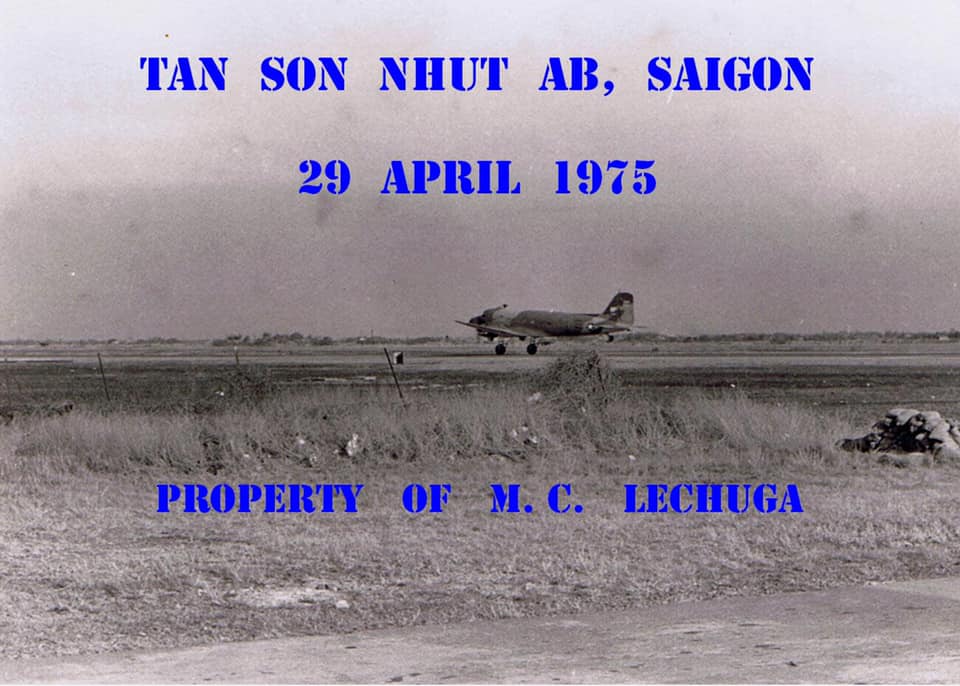

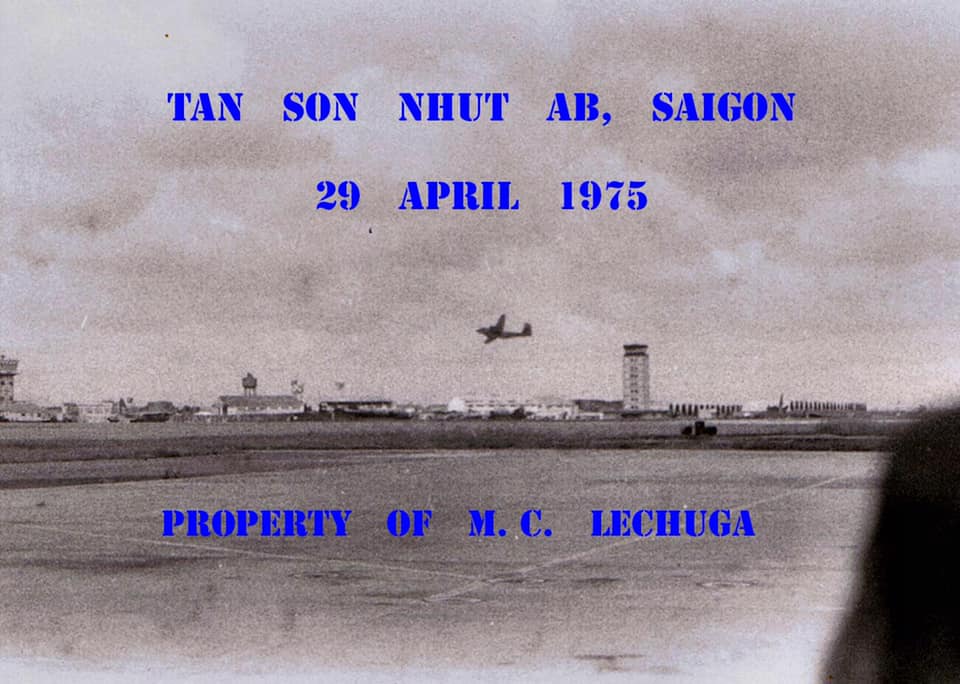

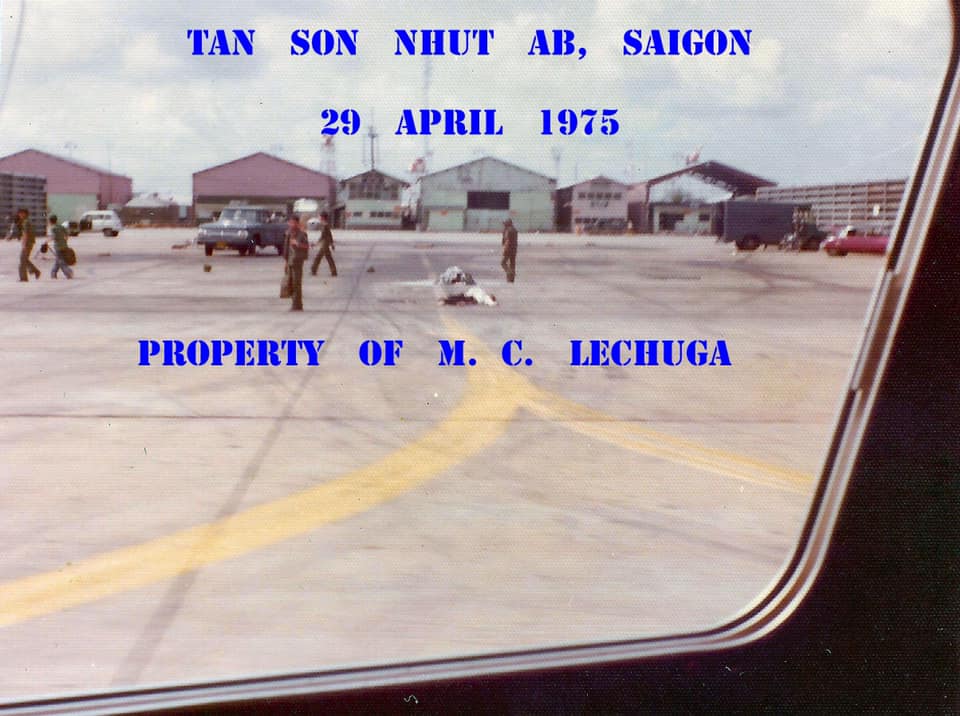

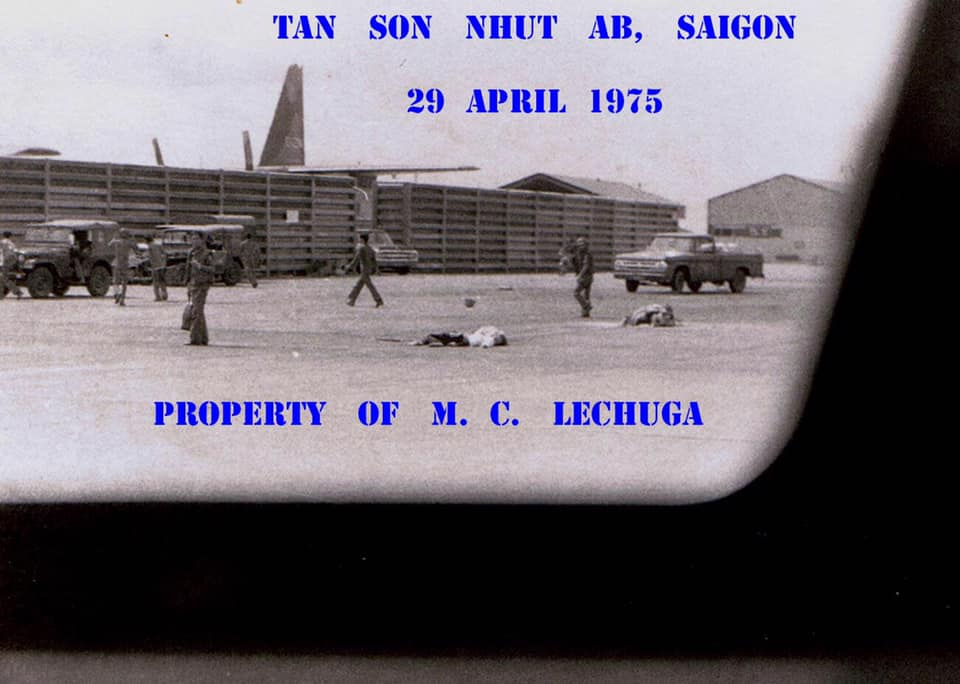

But not all South Vietnamese stayed and fought. As we stood at our station on the northeast flight line, we watched as the VNAF began its mass exodus from Saigon . . . . .

“We began to notice an increase in activity around the SVNAF aircraft areas nearest to our location. Crowds of people were going from aircraft to aircraft. Soon, we saw a C-47 take off. In the distance, helicopters were departing from the base.”

“The F5s canopy is open. We watched as the pilot stopped the F5 on the taxiway, opened the canopy, got out and ran to board the VNAF C130 on the right side of the photo. The VNAF C-130 backed out of the revetment and taxied out to the runway. As it prepared to take off, we noticed the crew entry door was open and two or three people were standing on the crew entrance door’s steps, clinging to the braided wire rope attaching the door to the aircraft’s fuselage.”

“Sadly, as the VNAF C-130 gained speed and altitude, the people lost their grip and fell.”

“A VNAF C-7 took off on a taxiway, its wings rocking, and we thought it would crash into the control tower. The C-7 labored to gain altitude, but it was still very low when we lost sight of it.” 29 April 1975 (Lechuga photo)

“Another C-7 attempted to take off from the runway, but it spun out of control as it lifted off the ground and crashed in a cloud of dust.”

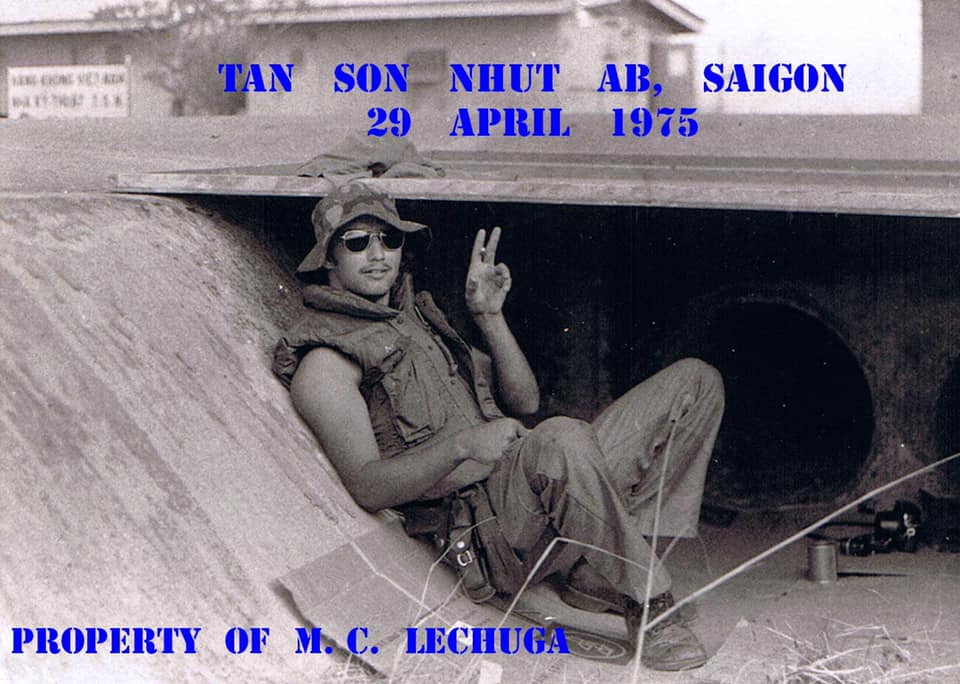

“We returned to our “home” on the northeast end of the base flight line to await further orders. We wondered if we were about to be attacked by the NVA ground forces. About an hour after the action we were equipped with helmets and flak vests. We were ready to party.”

“At approximately 0800 hours on 29 April, we went to survey the destruction caused by the bombing and the rocket attacks.” “Additionally, the aircraft parking and loading ramp we had been using was intact. This being the case, we were wondering if additional aircraft would be inbound. To me it seemed our small area of operations, Tiger Ops, and the DAO Compound were not targeted by the NVA.”

“However, after the tragic loss of the valiant SVNAF AC-119 gunship, a sense of impending doom could be felt. There was a change in the air.”

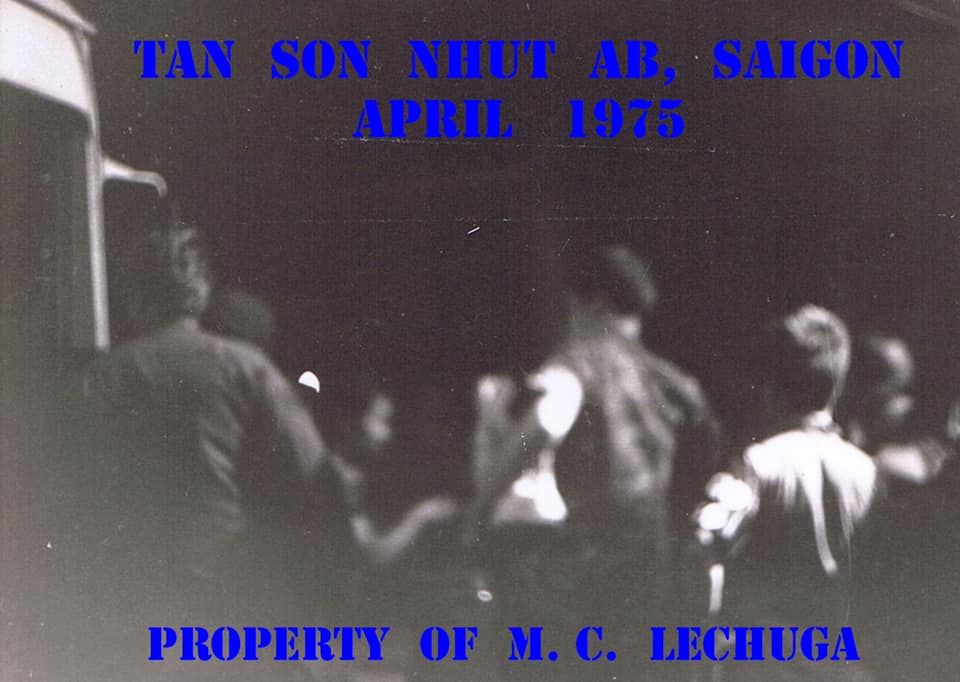

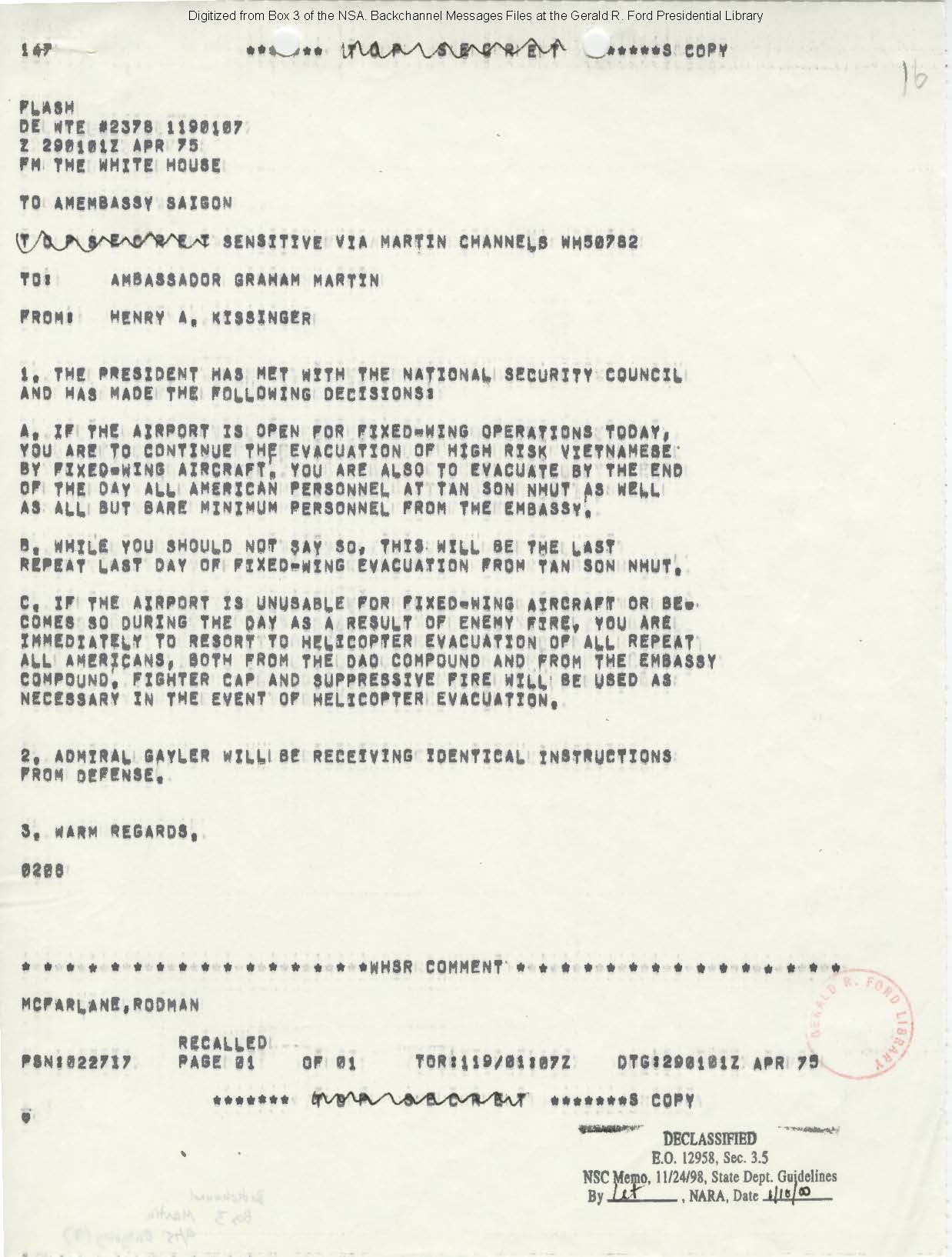

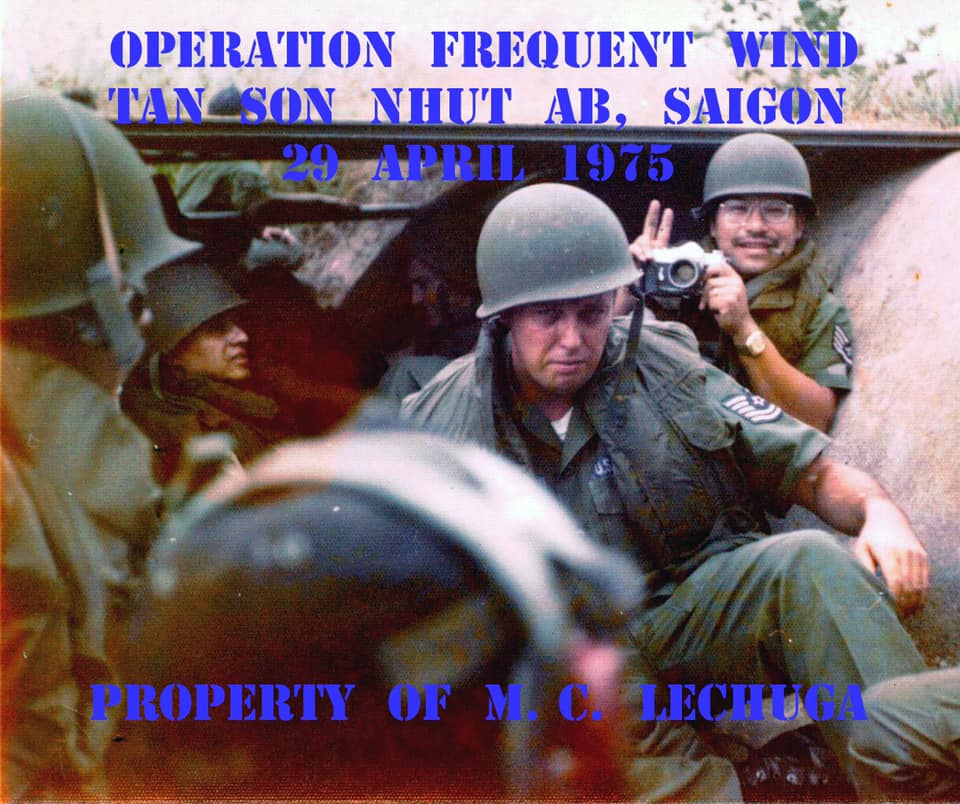

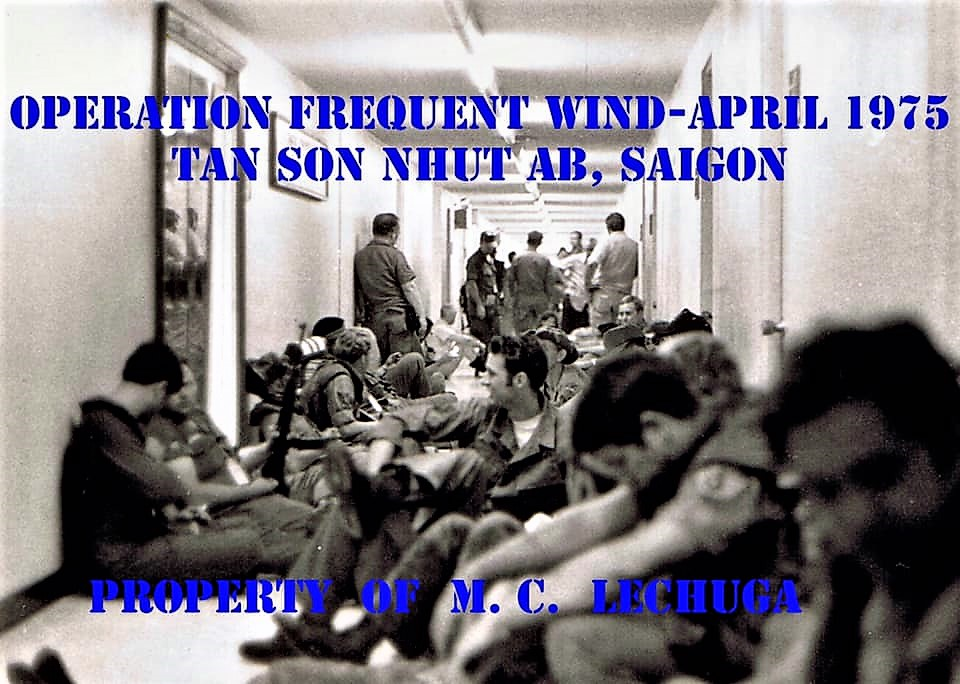

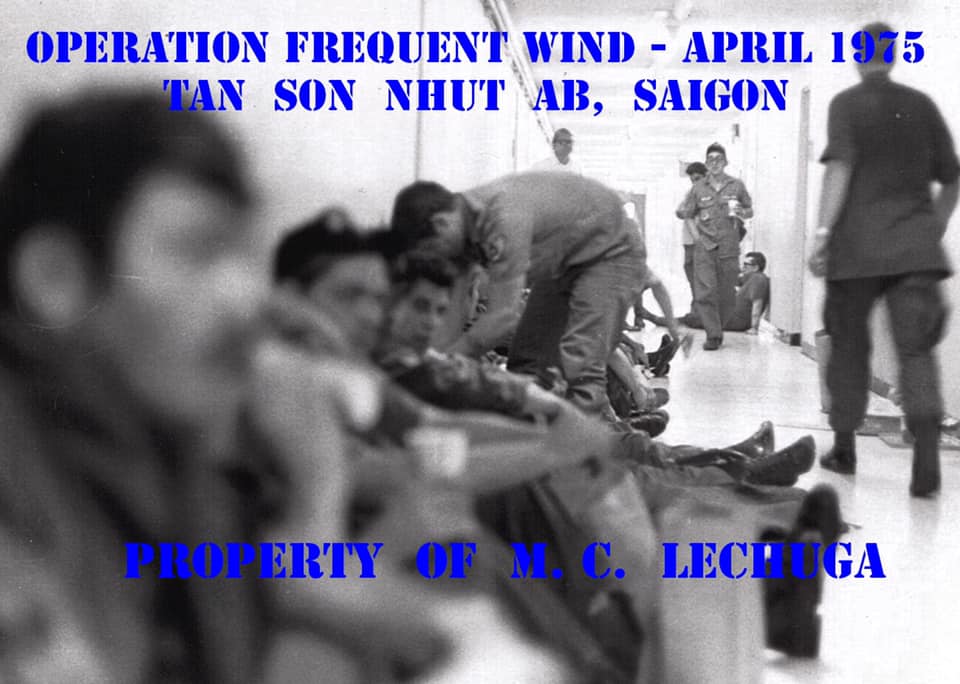

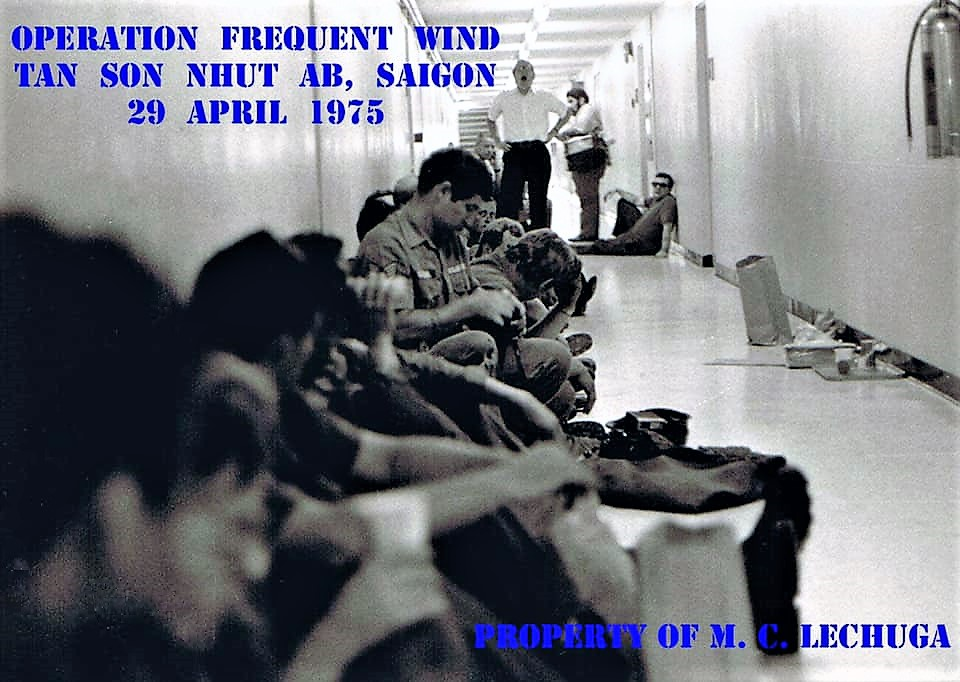

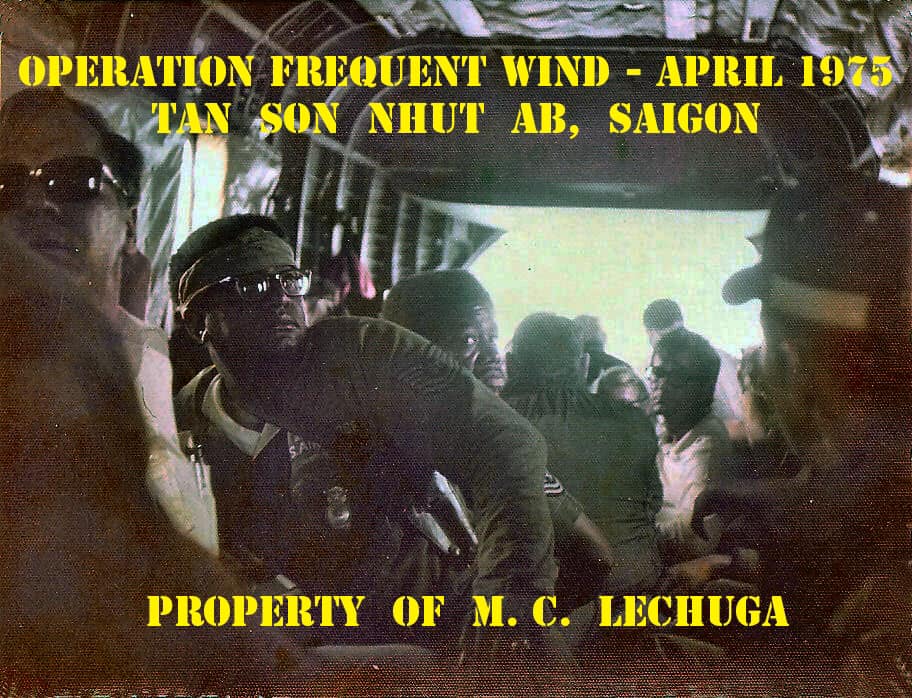

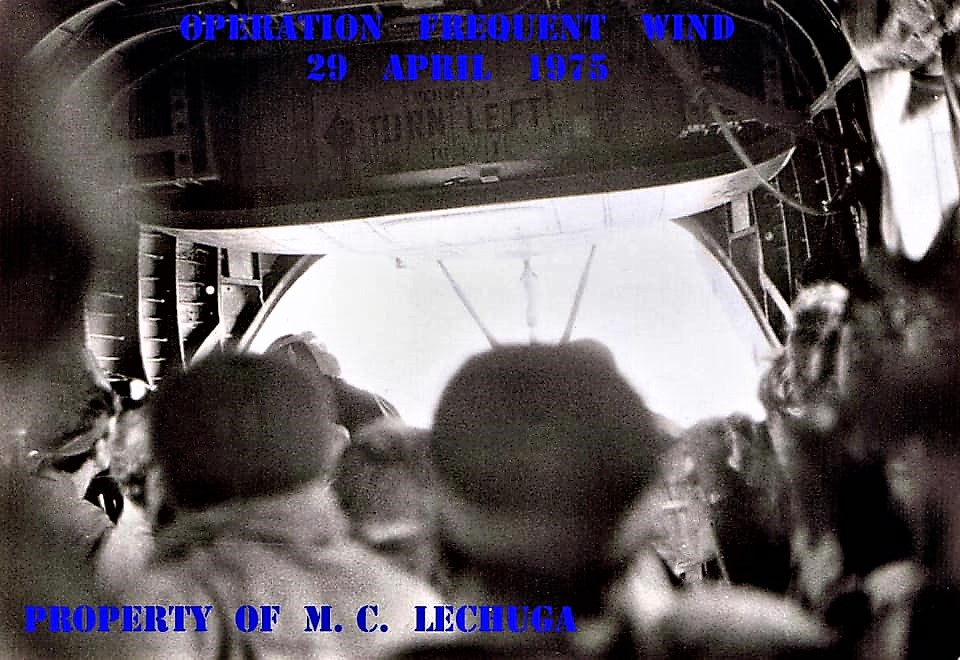

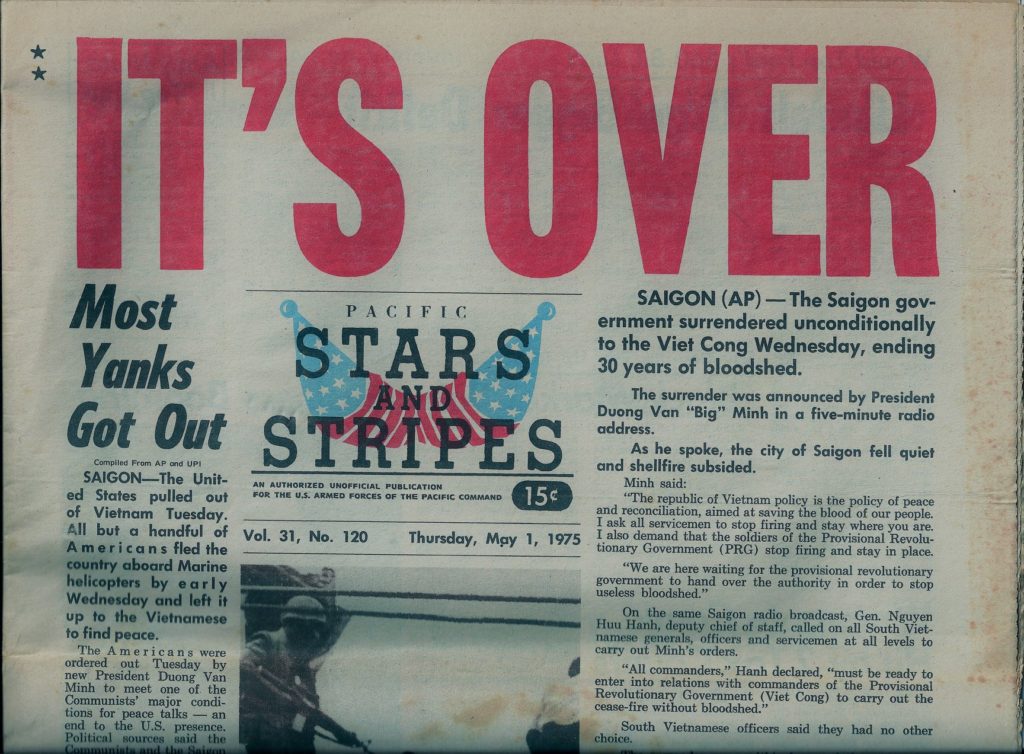

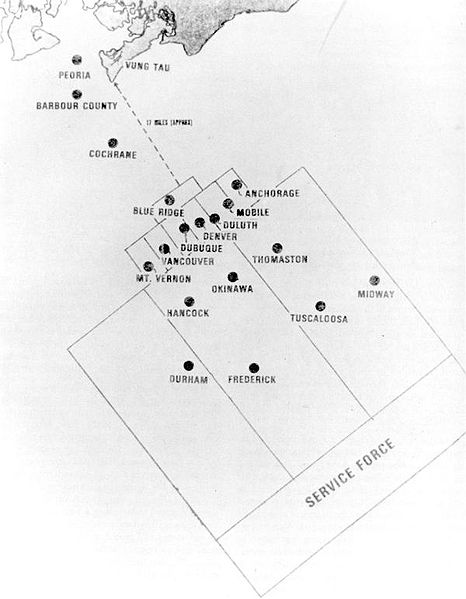

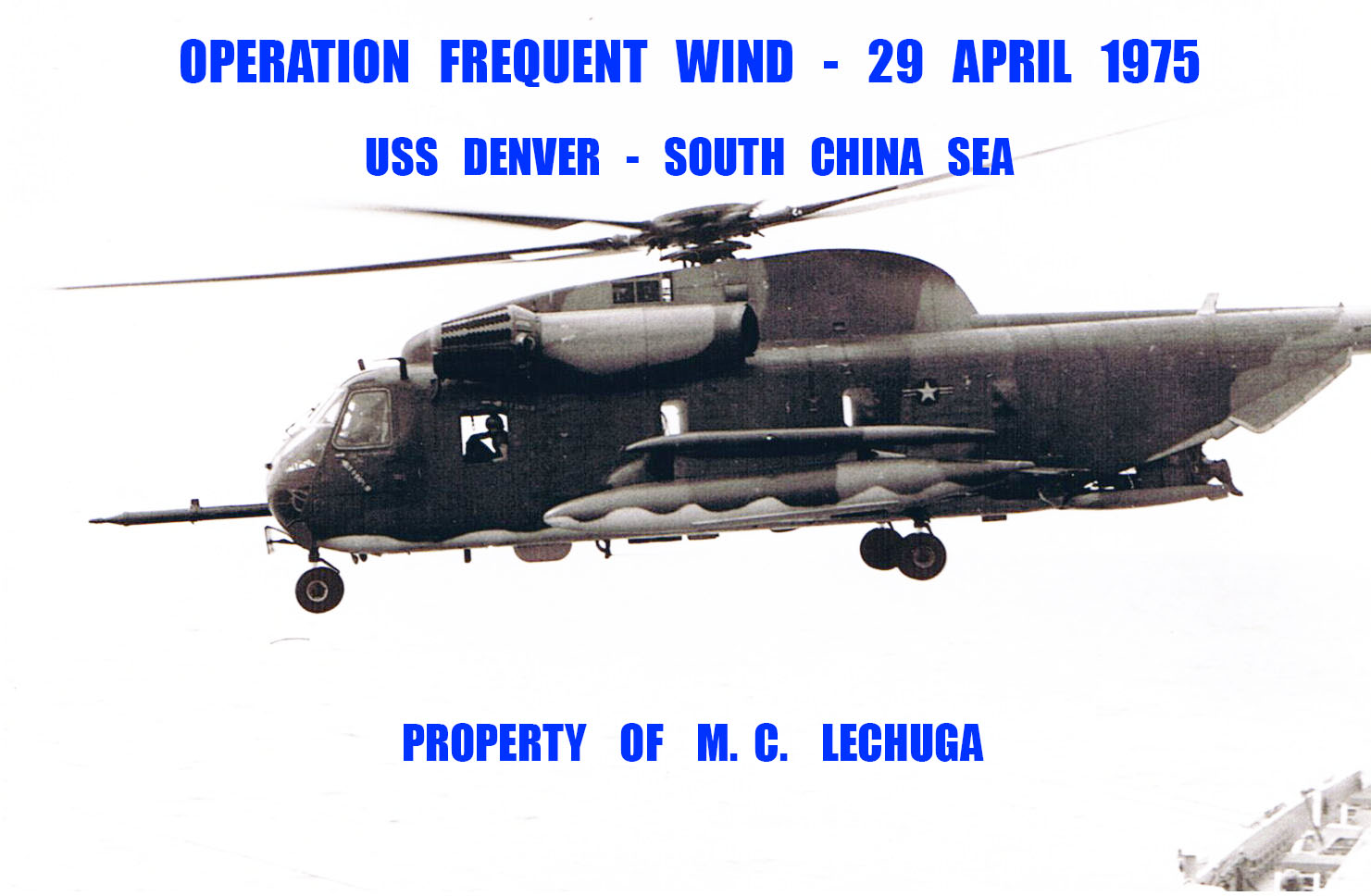

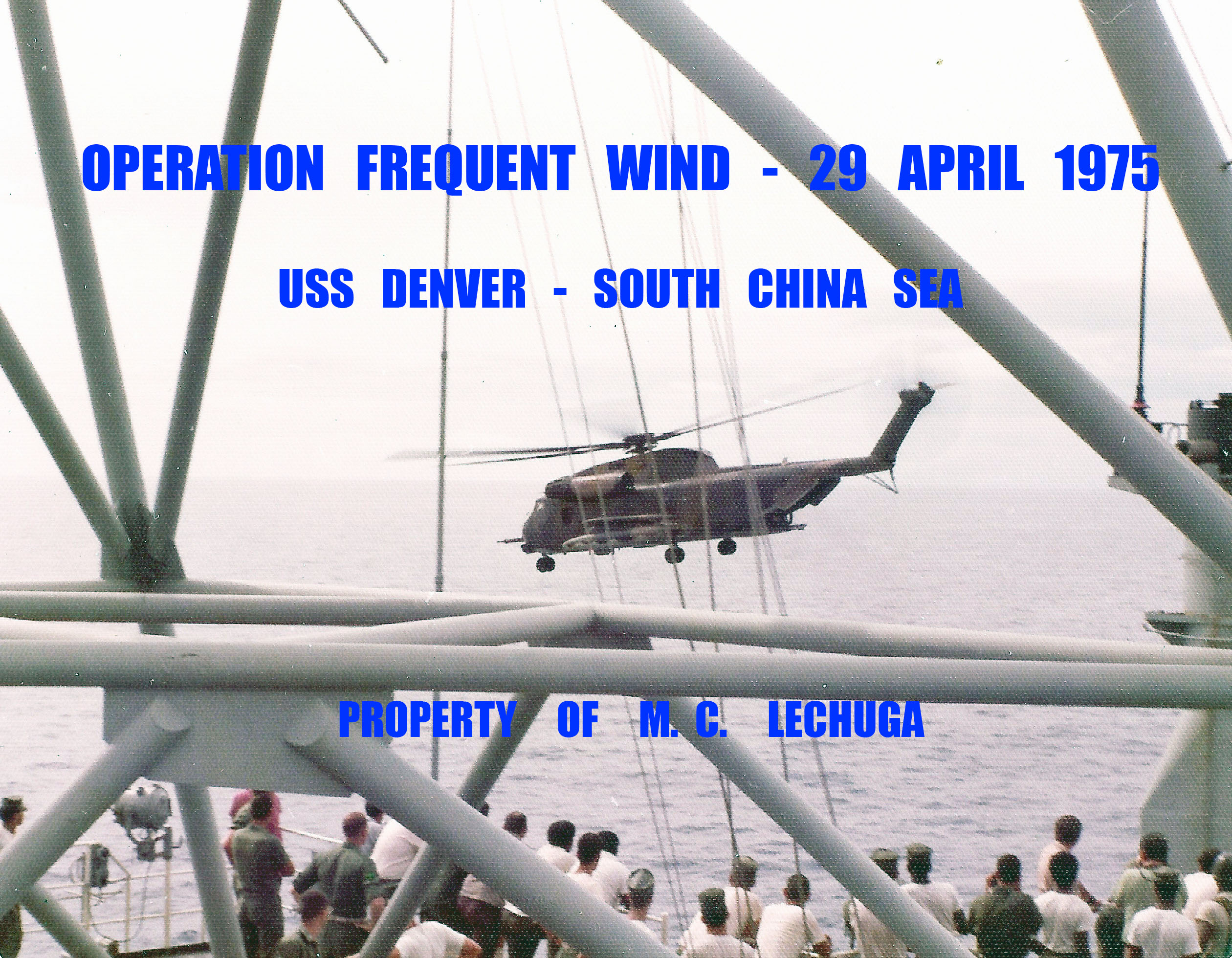

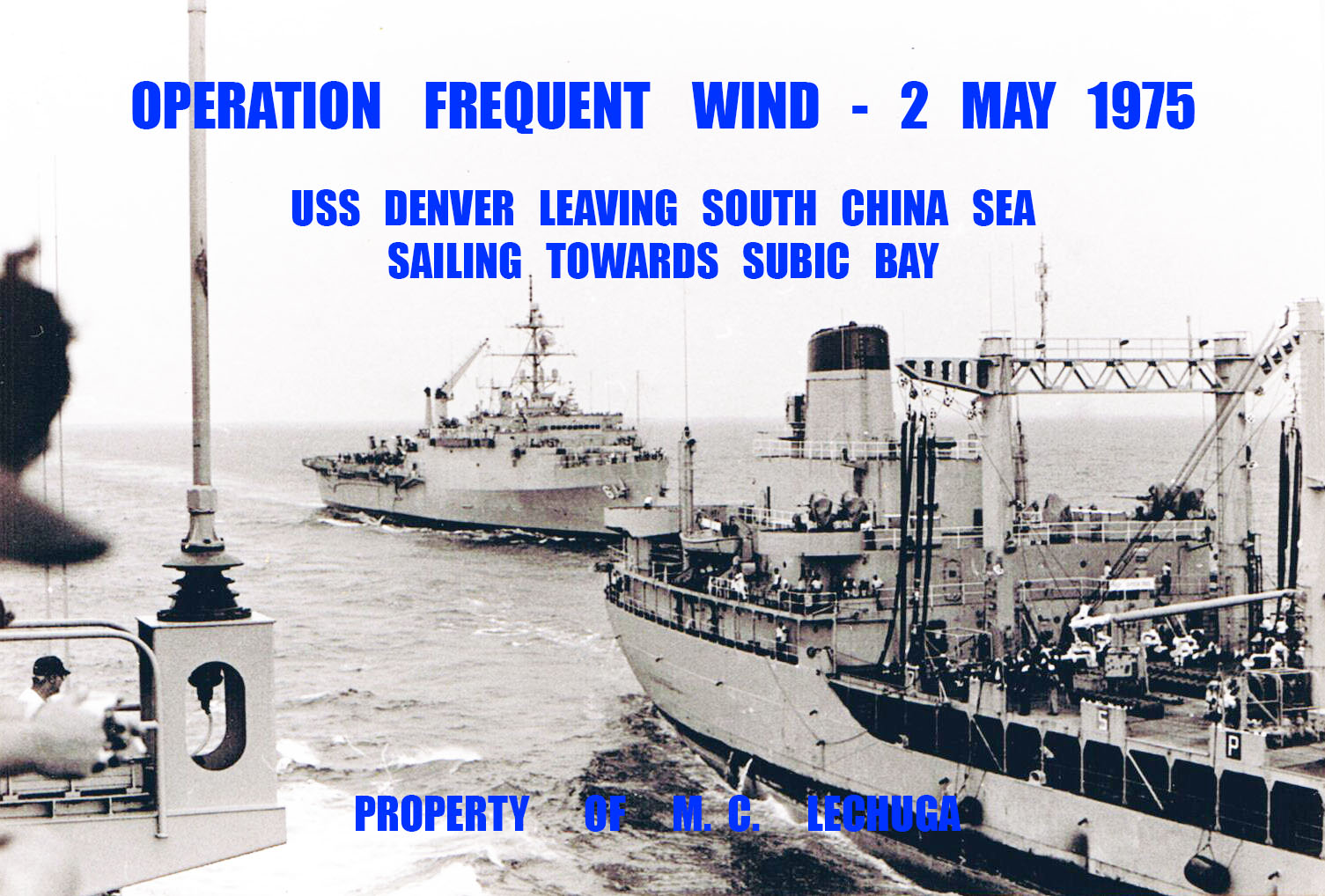

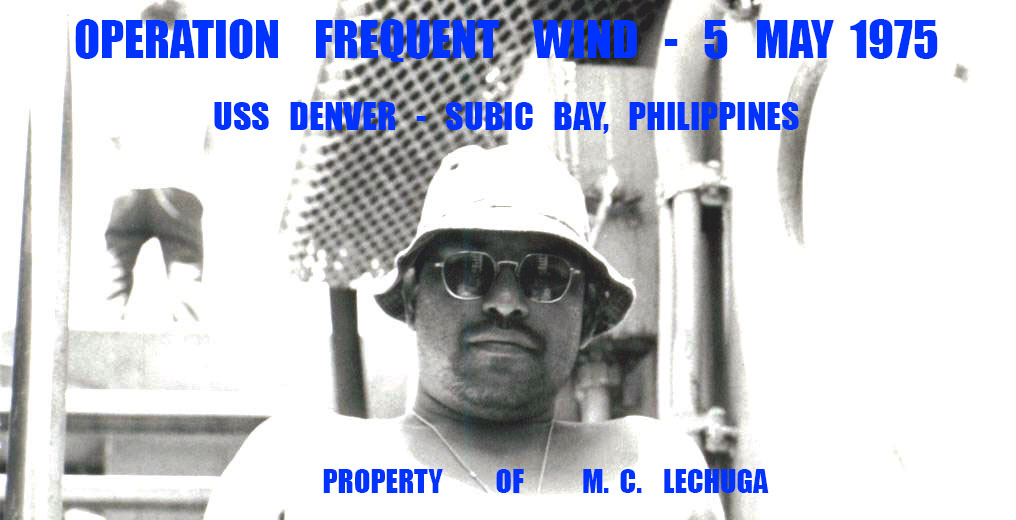

“29 April seemed like a very long day as we continued to watch the chaos around us and as we pondered the possibilities of the outcome.” “As the morning of 29 April progressed, we still did not know if, or when, the evacuation airlift effort would pick up again. So, we improvised our bunkers in the drainage ditches near us, and we practiced the well-known, “hurry up and wait.” At some point we were informed, no more aircraft would be coming in, but no word about how we would get out. So, we hunkered down and waited.” We get word to head to the USDAO compound and abandon our flight line quarters . . . . . . “At approximately 1400 hours, we received word to proceed to the DAO Compound for evacuation processing and extraction via Marine helicopter. We boarded two vehicles and slowly began to drive from our flightline home located on the north east end of the field across the ramp towards the direction of the DAO Compound.” “As we got underway, a vehicle full of armed SVN military stopped us and asked if we were leaving. We replied we were just going in to take a break. We continued toward the USDAO compound and they followed our vehicles. When we reached the entry control point, their vehicle made a U-turn and left the area. We all agreed, we had experienced a close-call.” “At approximately 1800 hours, our chalk ran to a waiting Marine helicopter. We piled in, elbow-to-elbow, and the chopper executed a combat ascent. Exhilarating! From the Defense Attache office building (formerly MACV Headquarters), huge clouds of black smoke could be seen rising from the impact of intermittent rocket ,and artillery shells on the main air base-barely a quarter mile away. Several blocks to the east, a huge fireball erupted in the vicinity of the Pacific Architects and Engineers’ warehouse, the building of a contractor who maintained the last of the US facilities in Vietnam. The blaze cast an eerie, flickering light on the whole area-where over 20 years of American effort was coming to an end.” “As we gained altitude, the helo crew had a person manning a machine gun at each side-window, and a lookout at the rear ramp scanning for missiles. We were nervous to say the least.” 29April 1975 (Lechuga photo) “We strained to see outside and we were able to catch a glimpse of the receding air base and the city of Saigon, then the coast of SVN, and finally the South China Sea. After about a 30-45 minute flight, we landed on the aft helicopter pad of the USS Denver, LPD-9.” 29 April 1975 (Lechuga photo) ” An USMC CH53 Sea Stallion discharges her passengers onto the USS DENVER off the coast of South Vietnam, 29 April 1975.” (Lechuga photo) Homecoming “The arrival back in the Philippines was anticlimatic. After arrival at the Subic port in the afternoon of 5 May 1975, the Clark AB people caught a ride over to Cubi Pt NAS. There we caught a Marine or Navy R4D (C47) 20 minute hop over the Zambales mountains to Clark AB. On arrival at Clark, we offloaded and I caught a taxi with the lone duffel bag I was able to escape with. Inside were two miniature Saigon elephants. Getting out of the taxi at the Clarkview gate, I walked the few blocks to my house. Welcome home honey. And, in true military fashion “I had to go in to work the next day”. During the month of April 1975, the U.S. Air Force flew 201 C-141 missions and 174 C-130 sorties and evacuated more than 45,000 people from Saigon, including 5,600 U.S. citizens. Still, the U.S. Ambassador, his staff, and many more U.S. citizens and refugees remained in South Vietnam. They would have to be evacuated by helicopter, in an operation known as Frequent Wind. While many of those helicopters belonged to the U.S. Marines, eight of the 21 SOS CH-53s and two of the 40th ARRS HH-53 helicopters flew evacuation missions alongside their USMC compatriots. Their flights marked the first significant deployment of USAF helicopters from a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier. In addition, U.S. Navy and USAF fighters flew escort for the helicopters while USAF AC-130 gunships and KC-135 tankers provided additional support. In dangerous circumstances, 71 U.S. helicopters flew 660 sorties between Saigon and the U.S. Seventh Fleet, evacuating more than 7,800 people from the U.S. Embassy and the Defense Attaché Office on April 29 and 30. The operation ended at 0900 on April 30, and by noon that day, Communist flags waved over Saigon’s Presidential Palace. On that final day, USAF aircraft flew a total of 1,422 sorties over Saigon.

At 10:51 on 29 April, the order was given by CINCPAC to commence Operation Frequent Wind, the helicopter evacuation of US personnel and at-risk Vietnamese.

With no more US aircraft scheduled to arrive at Tan Son Nhut AB, we wait and wonder about what the day ahead of us holds for us . . . . . . .

We board a USMC helicopter for our flight to safety

Off the coast of South Vietnam, the US Navy positions its ships to recovers the evacuees . . . . . . .

The helicopters leave the safety of the ships to return to Saigon to evacuate more people

The journey home to the Philippines . . . . . . .

Looking back . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .